“Imagine a journalist waking up with no Internet, no mobile phone network and not even a landline telephone,” says Peerzada Ashiq, The Hindu national daily’s correspondent in Srinagar, the Kashmiri capital, describing the experience that all reporters in this Himalayan valley shared on 5 August.

The communications blackout was imposed by the national government in New Delhi to coincide with the repeal of article 370 of India’s 1947 constitution, which granted a degree of autonomy to Jammu and Kashmir, a conflict-riven state riven that has become one of the world’s most militarized territories.

“For our era, for my generation, this is the most important event in history,” says Faisal Yasin of the Rising Kashmir regional daily. “And yet we’ve had no way of covering it. This is really awful.”

“What these journalists say is a damning verdict on the appalling conditions in which the media are trying to work,” said Daniel Bastard, the head of RSF’s Asia-Pacific desk. “Their stories are shocking. Technological obstruction, surveillance, intimidation, and arrests – everything is designed to ensure that only the New Delhi-promoted version of events is being heard. The Kashmir Valley’s population has been buried in a news and information black hole for the past 100 days. This situation is a disgrace to Indian democracy.”

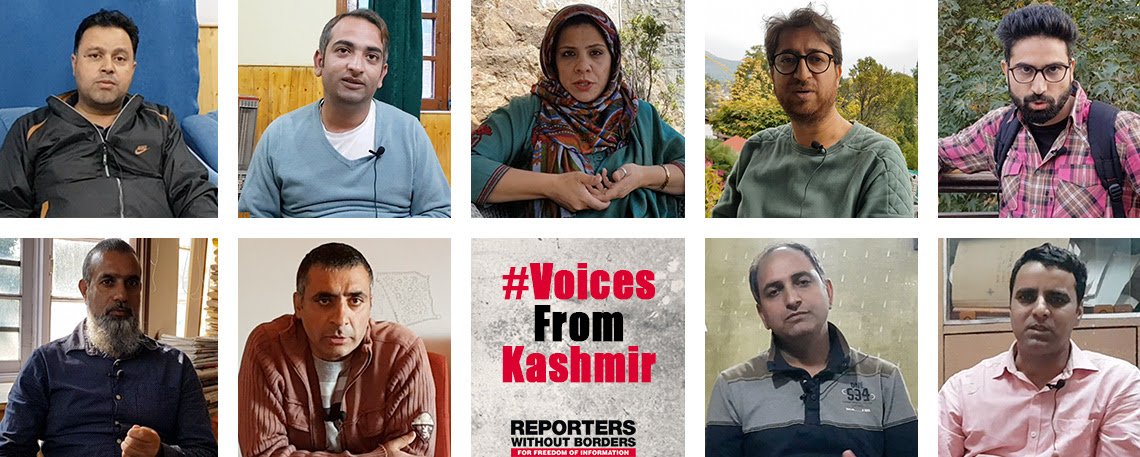

See the videos thread on RSF’s Twitter account

From the very first day, journalistic work has been blocked by specific obstacles. “You couldn’t call anyone and you couldn’t go out because of the curfew,” says Bashrat Masood, a reporter for The Indian Express. “And even when you managed to write an article, you had no way of sending it to get it published.”

“It’s as if we’d gone back to the Stone Age,” Press TV correspondent Shahana Bhat says. Reporters need a lot of ingenuity if the information they gather in Kashmir’s mountains is to reach the outside world. The biggest media outlets use couriers who fly to Delhi with their stories on a USB stick.

Complicated process

Ashiq has used a friend who works for a TV network and therefore has access to a satellite uplink. “I wrote my article by hand on a sheet of paper,” he says. “We filmed this sheet of paper, then we sent the video to his TV network in New Delhi and they sent the video file to my newspaper, which finally re-transcribed the article.” Such a complicated process obviously cannot be used on a regular basis. “A story that I used to be able to do in three or four hours now takes me at least five or six days, the Kashmir Reader’s Junaid Bazaz says.

For the sake of appearances, the Indian government set up a “Media Facilitation Centre” in Srinagar. “I don’t accept this name,” freelancer Athar Parvaiz says. “There were only four computer systems and one landline. And no Wi-Fi connection.” The authorities eventually doubled the number of systems, to a grand total of eight computers. To keep the world abreast of events in region with 8 million inhabitants, one could have expected a rather more substantial level of “media facilitation.”

“When you get to the Media Facilitation Centre, you have to queue up, you have to wait your turn to file a report.,” Ashiq says. “Sometimes it takes you as long as two or three hours.” And then each journalist is only allowed 15 minutes with the computer. “Imagine completing an entire newspaper, an entire 12-page newspaper, in a quarter of an hour,” Yasin says. “That’s something that normally takes 24 hours. It’s simply impossible.”

“Humiliating”

There is absolutely no respect for the confidentiality of journalists’ work and their sources at the centre. “It’s quite humiliating because your computer screen is visible to 20 other journalists when you are writing a very private message,” Ashiq says. Parvaiz recalls the day he was writing a message to an editor and a journalist behind him tapped on his shoulder in order to point out a typing mistake. “That’s a very concrete example of what confidentiality is reduced to,” he says.

The journalists who are forced to use the centre have no illusions about it. “As soon as they announced the centre’s creation, we immediately realized that all content entering or leaving Kashmir would be closely monitored,” says Hilal Mir, a freelancer who used to edit the Greater Kashmir magazine. “It’s obvious that [the authorities] have access to all the details of all the people using their Internet,” Bazaz adds.

Risky reporting

Reporting in the field is equally risky. “We quickly heard talk of widespread human rights violations but it’s very hard to verify information in the absence of any communications networks,” Ashiq says. Bazaz agrees: “Reporters based in outlying areas and rural areas have no way of sending stories to the media outlets they work for. So, there is no way of knowing what is happening in any place unless you actually go there.” But journalists who try to visit villages are stopped at paramilitary roadblocks and are treated abusively by the security forces that have sealed off the entire region.

“I had a run-in with the police,” Bhat says. “A cop started shouting at us, wanting to see if we’d shot any video footage. I asked what would happen if we had. He said, if we had, he would smash our camera.” The angry exchange of words ended with the policeman saying: “You’d better leave now before things get really nasty.”

“Scared into silence”

This episode is typical of the way the authorities harass journalists. “The first day, they randomly arrested journalists, announcing that some were detained for an hour or two,” Ashiq says. “The government probably wanted to send a message to the entire journalistic community, that they’re keeping close tabs on who we are, what we write, and who we work for.”

“There were rumours that at least 130 journalists had been blacklisted and could be arrested, so journalists were really scared, they were scared into silence,” Mir says. “We don’t know exactly how many reporters were detained,” said the NewsClick website’s correspondent Anis Zargar. “We will only get to know when the communication blockade is lifted.”

“Red lines”

This uncertainty has had a big impact on journalists, especially went they venture into the field. Zargar, for example, tried to verify reports of torture in Shopian, a district 50 km south of Srinagar. “In a way, you feel scared, anxious,” he says. “I realized that anything could happen to me, and I wouldn’t be able to warn anyone, I wouldn’t be able to call anyone. This is one of the main reasons why some journalists are censoring themselves.”

Ashiq adds: “I think the government has taken great care to make us understand what could happen to us if we cross the red lines. They are either going to order a journalist to report to a police station or they are going to issue indirect threats.”

“Monologue”

Surveillance, intimidation, threats, and arrests are all being used to harass Kashmiri journalists, and the media they work for have to be very careful, with the result that there is no longer any diversity of opinion. “There are subjects that newspapers are taking care not to tackle without being told by the government,” Yasin says. “For example, there are no longer any editorials.”

“If newspapers stop publishing editorials, they are refraining from expressing an opinion on certain issues,” Ashiq says. “And that shows that a certain kind of opinion has been banned from the newspapers. So, there’s a kind of monologue, one sought by the government, which doesn’t want a debate about the pros and cons of their repeal of article 370.”

Suffering

This appalling situation has gone on for the past 100 days without any real improvement. “We have constantly tried to resolve all these problems with the government,” says Ishfaq Tantry, the Kashmir press club’s general secretary. “We have engaged with the authorities at all levels without success. And journalists continue to suffer.”

Currently ranked 140th out of 180 countries in RSF’s World Press Freedom Index, India will probably fall further in the index as a result of the political crackdown on journalism in the Kashmir Valley.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia