By Michael Scollon

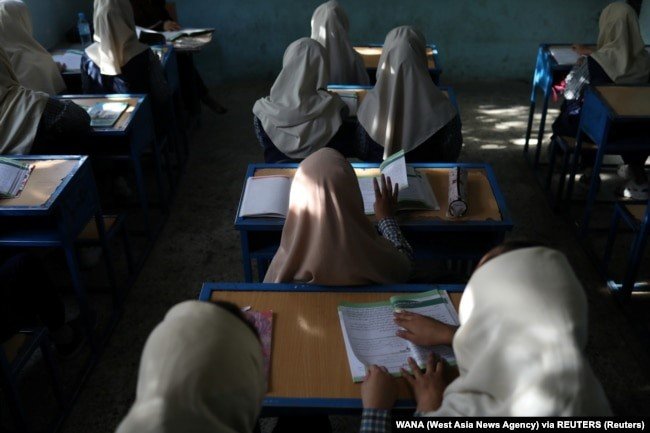

Hundreds of school-aged girls in Afghanistan are getting around the Taliban’s efforts to stymie their education by going online, giving them the opportunity to continue to learn everything from computer programming to sculpting to yoga psychotherapy.

“It sends a clear message to the Taliban,” said Maryam, who sees continuing her education under Afghanistan’s new hard-line rulers as a challenge. “Bring it on; we can promote our classes online. We will never stop the progress of our country.”

Maryam, who provided only her first name to RFE/RL’s Radio Azadi, is one of about 1,000 girls who have signed up to take classes with the Herat Online School since it was launched just weeks after the Taliban seized power in mid-August.

The school is the brainchild of Angela Ghayour, an Afghan-born educator who lives today in Brighton, Britain. Ghayour left the western city of Herat as a child in the early 1990s to escape the devastating civil war in Afghanistan and realized while living as a refugee in Iran that she had a knack for education.

The school’s name is a nod to her native city of Herat, but the courses are available free of charge to girls anywhere in Afghanistan or elsewhere with access to the Internet, including Afghan refugees in Iran who have been denied an education.

“The goal is to prevent discrimination in education,” Ghayour said in written comments to RFE/RL. “In Afghanistan, gender discrimination has deprived girls and women of their right to education. In Iran, Afghan families are discriminated against in education because they do not have residence permits.”

Ghayour lists potential students’ and teachers’ lack of access to mobile phones and the Internet as the school’s biggest hurdle.

“I see girls studying at night because their father works outside the home during the day and the smartphone is not at home,” Ghayour said. “So, the girls wait for their father to come home, and then use his smartphone to go online and learn.”

While Ghayour, teachers, and managers volunteer their services, the school collects donations to help students get connected.

“The Herat Online School started the day after the Taliban entered Herat with the motto ‘the pen instead of the gun,’” Ghayour said of the Taliban’s capture of the city just days before it took the capital, Kabul, on August 15.

“Even before they closed the doors of universities and schools to girls, there were fears that the same story would repeat itself and women would be deprived of education and jobs for years by the Taliban,” Ghayour said.

“Because of my years of experience teaching Persian literature to bilingual children from afar, which also yielded good results, I decided to teach Afghan girls with the help of volunteer teachers from around the world.”

Students say that the school provides a lifeline to their future education.

“Through the online school in Herat, we wanted to continue our lessons with the arrival of the Taliban and take advantage of the opportunity that has been created for us,” a student named Fatemeh told Radio Azadi.

“The online school in Herat became a window of hope for all the girls who were concerned,” she said. “They can no longer afford not to be able to study.”

The fears that their education would end are not unfounded. When the Taliban was last in power, from 1996 to 2001, its strict interpretation of Islam barred girls from going to school and women were banned from both work and education.

The Taliban has attempted to assuage concerns that it will return to its brutal style of rule, saying just days after taking control that it was “preparing for the education of high-school girls as soon as possible.” But the extremist group then issued a blanket ban on the education of girls over the age of 7 — grades six to 12.

And while the ban is not being enforced in some areas — girls have since been allowed to return to both private and state-run secondary schools in five northern provinces, and the Taliban authorities recently announced that a women’s-only institute, the Moraa Education Complex in Kabul, will provide education for orphaned girls — obvious concerns remain.

Even under the previous government’s comparatively liberal view on girls’ education, more than one-third of girls over the age of 15 were illiterate as of 2019, according to government statistics.

In September, UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed called on the international community to support Afghan women and prevent a reversal of the two decades of gains in girls’ education that followed the Taliban’s ouster in 2001, after which millions of girls enrolled in school.

“You can be assured that we will continue to amplify your voices and make it a zero condition that girls must have an education before the recognition of any government that comes in,” Mohammed said during a panel discussion on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly.

The Taliban government has yet to be recognized by any country, in part because of the previous regime’s legacy of terrorism, brutality, and its stance on girls’ and women’s rights.

The course offerings at the Herat Online School include several classes that could potentially be at odds with the Taliban’s belief system.

Music, for example, has been banned by the Taliban, although the militant group’s position has been inconsistent. The arts have also suffered previously under the Taliban.

Yet art classes, sculpting, calligraphy, music, and even yoga psychotherapy are on offer by the Herat Online School.

Already about 200 teachers are working with the school, and another 300 volunteers are at the ready. The school works just like any other, with tests and student evaluations.

“The establishment of the Herat Online School proves one thing,” Ghayour told RFE/RL. “The Afghan people have reacted negatively to the Taliban and will resist.”

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia