Regional powers are seeking to fill the vacuum left by the US and its Western allies

News Desk

Is Afghanistan set to become a battleground for the new ‘Great Game’ after the abrupt exit of the US-led allied forces from Kabul this August?. Regional powers are seeking to fill the vacuum left by the US and its Western allies, writes Ron Synovitz, correspondent of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

In an article published on RFE/RL website, he examines whether Afghanistan is set to become the scene of another competition between global powers after the US departure this year that prompted China, Russia, Iran, and Pakistan to reposition themselves in the region.

“There may be a new Great Game in Central Asia, but it is going to have a lot less important to the United States than the new Great Game in the Western Pacific and East Asian waters,” Mr Synovitz quotes James Reardon-Anderson, a professor of history at Georgetown University, as saying. The professor alludes to Washington’s growing competition with Beijing.

The renewed competition, however, is unlikely to have any clear winners

“China and Russia project an appearance of coordination, but in practice, their differing regional interests and identities set real limits,” Sabine Fischer and Angela Stanzel noted in a recent analysis for the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

The chaotic withdrawal of US and NATO forces from Afghanistan and the lightning collapse of the internationally recognized government in Kabul in August spelt the end of the West’s a nearly 20-year foothold in the war-torn country.

Now, with the Taliban back in control of Afghanistan, other powers that have fallen out with the West or are considered its rivals are vying to fill the void.

There have been predictions that the geopolitical realignment could transform the Central and South Asian region into a hub of anti-Western sentiment.

Some analysts say that Russia, China, Pakistan, and Iran could come together in the next chapter of the Great Game — a reference to the 19th-century struggle between great powers for dominance over Afghanistan, a strategically located nation in the heart of Asia.

But others argue that Moscow, Beijing, Islamabad, and Tehran are each merely looking to advance their own interests in the new geopolitical order.

Shift to East Asia

Washington made it clear as far back as the Obama administration that it was withdrawing from Afghanistan in order to shift its global focus on China.

James Reardon-Anderson, a professor of history at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, predicted then that the withdrawal would lead to the disappearance of US influence in Central Asia.

“There may be a new Great Game in Central Asia, but it is going to have a lot less important to the United States than the new Great Game in the Western Pacific and East Asian waters,” Reardon-Anderson told RFE/RL in 2013.

In defending the US military withdrawal from Afghanistan, President Joe Biden said the “world was changing” and that Washington was “engaged in a serious competition with China.”

“And there’s nothing China or Russia would rather have, would want more in this competition than the United States to be bogged down another decade in Afghanistan,” he said in a speech on August 31.

But some observers have said that the pullout from Afghanistan could complicate, not enable Biden’s “pivot toward countering China.”There has also been criticism by US allies and lawmakers that, by leaving Afghanistan, Biden has amplified the terrorism threat to the U.S. homeland.

The Taliban, which is still allied with the Al-Qaeda terrorist network, is fighting an escalating war with the rival Islamic State (IS) militant group, which observers say has been boosted by the West’s retreat from Afghanistan.

The Biden administration has said that it will counter any terrorist threats from Afghanistan with an “over-the-horizon” mission. But there is scepticism over the mission’s effectiveness at neutralizing threats emanating from the region.

Meeting with NATO diplomats in Brussels in November, U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas West signalled the rising importance of other powers in the region following the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan.

West said it was “imperative” that NATO allies work “with the region — with Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, and the Central Asian states — on our common and abiding interest in a stable Afghanistan that does not represent a threat to its neighbours, is at peace with itself, and respects human rights, women’s rights, the rights of minorities, and so forth.”

But notably, while the United States and its NATO allies continue to demand that the Taliban respect human rights and women’s rights, such calls are not being issued by Moscow, Beijing, or Islamabad.

Shi’a-rule Iran has insisted that it will not officially recognize the Taliban government until its Sunni leadership creates an “inclusive” cabinet in Kabul that includes Shi’a members of Afghanistan’s Hazara community.

Meanwhile, different approaches on development, counterterrorism operations, and the fight against drug trafficking make cooperation difficult between the West and the new regional power players.

The reconstruction plans of the US and European Union were focused on civilian aid, development assistance, and police reforms as part of a state-building strategy.

China and Russia are now focused on preventing Islamic extremism and drugs from spreading out of Afghanistan into Central Asia and China’s western Xinjiang region.

For its part, Tehran fears Taliban-backed Sunni militants infiltrating eastern Iran from Afghanistan.

The Iranian government is also concerned that the Taliban could use opium smuggling into Iran as part of a strategy to undermine Tehran’s authority.

Kirsten Fontenrose, director of the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs, says countries that have “functional relations with the Taliban” are China, Russia, Pakistan, Qatar, and Turkey.

Of those, Fontenrose says, Qatar is “the only one of these countries without either hostile intentions toward the United States or a list of concessions it hopes to obtain” from Washington.

Fontenrose says the “nature of the withdrawal from Afghanistan” has U.S. allies in the broader region “wondering whether Washington is flying by the seat of its pants all across the region.”

Regional interests, global game

At the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), experts Sabine Fischer and Angela Stanzel say Russia and China are benefiting most “on the global level” from “the weakening that the West has been experiencing” since its withdrawal from Afghanistan.

But they argue that neither Moscow nor Beijing have found solutions for serious regional security challenges they are now confronted with.

“From the Chinese and Russian perspectives, the withdrawal from Afghanistan is further evidence of the progressive weakening of the Western alliance,” Fischer and Stanzel wrote in a recent analysis.

They say this bolsters the narratives from Moscow and Beijing that call for an end to the Western-dominated liberal world order.

“But those who limit the perspective of both actors to the global level will fall short,” Fischer and Stanzel warn.

“The failure of the West does not automatically mean gains for Beijing and Moscow,” they argue. “After all, China and Russia must also confront the dangers that could emanate from Afghanistan at the regional level and directly endanger Chinese and Russian interests.”

Other experts argue that Pakistan sees itself as the biggest regional winner, at least in the short term.

They say Taliban control of Afghanistan gives Pakistan strategic depth against its main rival, India because the Taliban-led government in Kabul can be influenced by Islamabad.

But critics of that view note that Islamabad has its own regional irritant — the fact that the Pashtun-led Taliban has never recognized the 19th-century British Colonial frontier between Afghanistan and Pakistan as an official border.

That leaves open the potential for territorial claims by the Taliban-led government on tribal regions of Pakistan that are the power base of Taliban Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani and his Haqqani network.

Pakistan’s “all-weather friendship” with China will allow Beijing to exert its influence in Afghanistan, observers say.

Experts say Moscow’s calm reaction so far to an expanding Chinese presence in Central Asia merely indicates that Russia is ready to tolerate a greater role for Beijing in regional security — not necessarily to cooperate on their long-term geopolitical goals.

That is because the common interests for China and Russia in Afghanistan diverge on issues like the role of India in the region and Central Asian security.

“Despite recent cooperation in the region, Chinese and Russian interests in Central and South Asia are not identical,” Fischer and Stanzel conclude. “China and Russia project an appearance of coordination, but in practice, their differing regional interests and identities set real limits.”

“China aims to integrate these regions economically into the Belt and Road Initiative while keeping Indian influence at bay and addressing perceived security threats to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,” they say.

By contrast, they say Russia wants to maintain its role as the primary security provider of a “greater Eurasian region” through the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Moscow also wants to balance its long-established relations with India against a new approach to Pakistan, they say.

Under the umbrella of the CSTO, Russia has expanded its military presence in Central Asia through a series of joint counterterrorism exercises on Tajikistan’s border with Afghanistan.

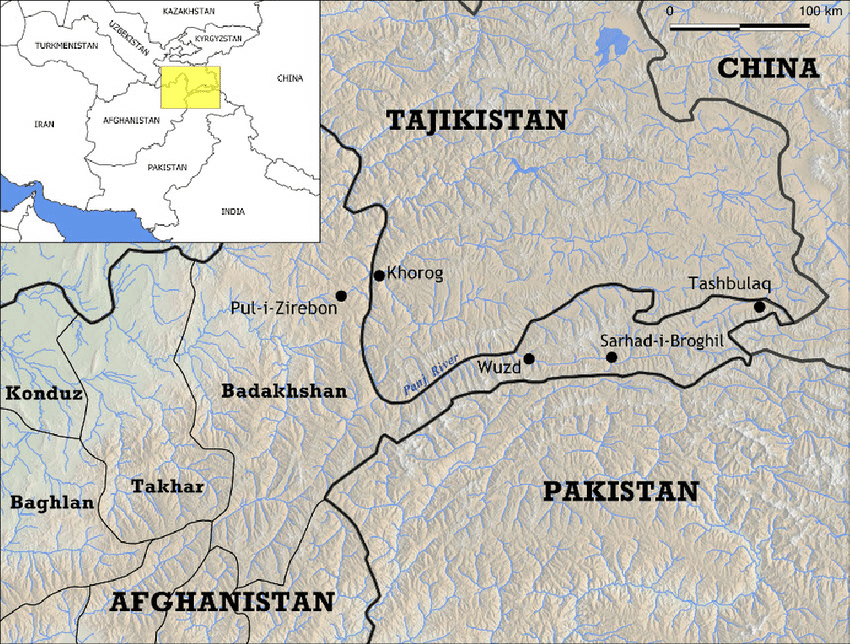

But an investigative report by RFE/RL’s Tajik Service revealed in October that China has also been expanding its military presence at a base in the far eastern corner of Tajikistan, near the area where Tajikistan, China, and Afghanistan meet.

Meanwhile, although Russia and China have agreed at meetings of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) that coordination is needed by all SCO members toward Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, they have not announced any road map or detailed proposals on working together.

Since the Taliban’s return to power, talks have been hosted by Pakistan, Russia, and China under what is known as the “troika plus” process in Afghanistan. That grouping also includes the United States.

None of the group has formally recognized the Taliban-led government in Kabul. But Pakistan, Russia, and China have also had their own bilateral meetings with Taliban leaders.

Iran has also not formally recognized the Taliban. In October, Tehran also hosted a meeting with Russia and officials from countries neighbouring Afghanistan to discuss the geopolitics of the region and security concerns. Taliban delegates were not invited to those talks.

Meanwhile, in early December, a tense situation along a segment of the Iran-Afghanistan border deteriorated into armed clashes between the Taliban and Iranian border guards.

Iranian state media later said the violence was the result of a “misunderstanding” by the Taliban.

Blaming the West

Part of Iran’s diplomatic outreach to the Taliban regime has been to blame Afghanistan’s chaos and humanitarian crisis on America’s two-decade presence in the country.

President Ebrahim Raisi has said that “Iran backs efforts to restore stability in Afghanistan as a neighbouring brother nation.”

Ali Akbar Velyati, an advisor to Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has described Taliban-ruled Afghanistan as “part of an Axis of Resistance with Iran at the centre” of countries seeking “resistance, independence, and freedom.”

But Jamshed Choksy, a professor of Eurasian and Iranian studies at Indiana University, says such rhetoric belies the deep concerns many in Tehran have about the Taliban. Ismail Qaani, the commander of the Quds Force of Iran’s powerful Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), warned the Iranian parliament in September that sectarian friction cannot be allowed to spread across the border from Afghanistan.

Qaani declared that sectarian rivalries in the past have shown that the new Taliban regime is “no friend of Iran.”

“Tehran’s revolutionary leaders periodically even publicly cheer the Taliban victory — mainly because the U.S. withdrawal permits Iran freer rein across the region,” Choksy says. “Yet the potential of Afghanistan becoming the global hub centre of terrorist training robs Iran of true satisfaction.”

“The danger from re-Talibanized Afghanistan may also compel greater reliance on Russia and China, a situation which would undermine the independence so dear to many Iranians,” Choksy adds. This opinion article was first published on RFE/RL website.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia