While working in the archives of the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, I came across an interesting document. It was a list of the tools of Tarifbai Tillabayev, a zargar (jeweller) from Samarkand who worked in the mid-20th Century. The tools were purchased in November 1948 and compiled by the legendary ethnographer Olga Sukhareva.

According to the list, the tools — among which there were such instruments as otashgirak (tongs), gaichi zargari (jeweller scissors), and tustak (tweezers) — belonged to the Samarkand Museum. I wrote to the museum, although frankly speaking, I had no expectation of finding anything; after all, a lot of time had passed since then.

Imagine, then, my surprise when I found out that the instruments mentioned on the list are still part of the collection of the Samarkand Museum. It was even more surprising to learn that contemporary jewellers from Central Asia use tools almost identical to those that were in use almost a century ago.

Moreover, they create silver ornaments similar to those that existed in the 19th century, crafting them on the basis of photographs of rare surviving masterpieces. This process weaves the rich traditions of the past into the everyday present.

Past

In Turkestan, jewellery production was mainly concentrated in the cities of Andijan, Bukhara, Karshi, Kokand, Samarkand, Tashkent, Shakhrisyabz, Urgench, and Khiva. There were also specialized kishlaks of zargars, such as Zargarlik near Jizzak (Fahretdinova 1983, 71).

In the Transcaspian area, jewellers were present not only in the city of Merv but also in every large Turkmen village. The best works of embossing, filigree, openwork carving, cloisonné, and turquoise-encrusting were made in Bukhara. Kokand was famous for its niello and enamels.

The peculiarity of the jewellery art of Samarkand masters consists in the use of the openwork filigree technique. Urgench, Merv, and Khiva are known for massive cast decorations, such as the bracelets without closures (bilesik) that adorned Turkmen women.

Among the ranks of jewellers were not only Tajiks, Turkmens, and Uzbeks, but also Jewish masters, Persians, Lyuli Gypsies, Indians, and Dagestani-Laks. It is believed that the latter brought a new jewellery technique, niello, to Turkestan.

From the second half of the 19th Century, not only new techniques but also new shapes began to appear. Local jewellers mastered the production of so-called European jewellery. Accompanied by the penetration of European/Russian fabrics, accessories, clothing styles, and even food, this was an inevitable process that intensified with the annexation of Turkestan to the Russian Empire, when Russian settlers — among whom were masters of applied crafts and representatives of Russian trading houses and factories — arrived in the region.

The manufacture of “European jewellery” indicates, among other things, that there was a fashion for European items in Turkestan in the 19th Century, just as there was a fashion for Central Asian ones in Russia and for Oriental ones more broadly in European countries. In the eyes of the inhabitants of the Orient, Europe was as much enshrouded in a veil of exoticism as the Orient was for attendees at elegant balls in Paris in the 18th Century.

Most of the jewellery produced in Turkestan was made of silver, although gold was also widely used in Bukhara from the end of the 19th Century. During that period, bars of gold and silver were brought from Russia; silver was also imported from China. But bullion of precious metals was a luxury; more often, the basis was an alloy of Chinese, Russian, and Persian coins. Among other precious materials, carnelian and coral were imported from India and Europe, turquoise from Khorasan, and pearls mainly from Europe, while glass beads were both local and European in origin.

To become a master jeweller in Turkestan in the 19th Century, one had to either be born into a jeweller’s family or apprentice to a recognized jeweller.

The second route was especially difficult. Jewellers were not interested in transferring their professional secrets to outsiders, so the apprenticeship period could be longer. The apprentice was not taught, but only allowed to look closely at what the teacher was doing; the latter usually deliberately kept the secrets of craftsmanship to themselves. After about four to five years, a master had a well-trained apprentice who worked for his teacher for another five to 10 years for free before being initiated into the profession. Among Bukhara zargars, initiation was obligatory: it was considered that the absence of his teacher’s blessing would lead to failure in an apprentice’s work (Sukhareva 1962: 52).

Present

In contemporary Central Asia, the art of jewellery is far from forgotten. Across the region, jewellers create beautiful works of art that call to mind the masterpieces produced in the century before last. Here are some notable jewellers from the region.

Suhrob Akhramov (Samarkand, Uzbekistan) trained as a jeweller at the artisanal lyceum in Tashkent. He is 52 years old, but he enrolled in the lyceum when he was 24, which means that he has been in the profession for almost 30 years.

He has vast experience and has mastered many jewellery techniques. Suhrob specializes in making jewellery on the model of antique items and is also engaged in the restoration of such items. For example, they recently brought him an antique earring and the master is working on making a similar one. Another example of his craft is a magnificent tilla-kosh (headpiece) made by the jeweller on an old model.

This type of jewellery is still popular in Samarkand, where it is bought for brides. The zargar buys his tools in a specialized store and makes kolyb (stamps) himself on the model of antique ones. Customers bring him their own gold, silver, and precious stones; the jeweller also remelts “ancient coins, spoons, and everything he comes across.” He makes glass beads himself.

Shavkat Khatamov (Bukhara, Uzbekistan) did not grow up in a family of jewellers; his father was a carpenter. When he was 25, he went to learn jewellery-making from a Daghestani Lak ethnic craftsman who subsequently emigrated to Israel.

Shavkat learned a lot from his teacher and he later taught his son jewellery craftsmanship. Among the jewellery created by Shavkat are modern “European” styles as well as those that reproduce the jewellery of the late 19th and early 20th centuries from old photographs.

“I’m passionate about recreating old masterpieces,” Shavkat says.

Among his tools are rare old kolyb (stamps) and others he has made himself. Today, kolyb made in Afghanistan are brought to Central Asia, but they are expensive and lack “clarity of ornamentation and pattern.” The master makes his kolyb from bronze and steel; making a bronze kolyb is a complicated process.

Shavkat Khatamov’s work can be seen on his Instagram page (https://www.instagram.com/shavkatkhatamov/).

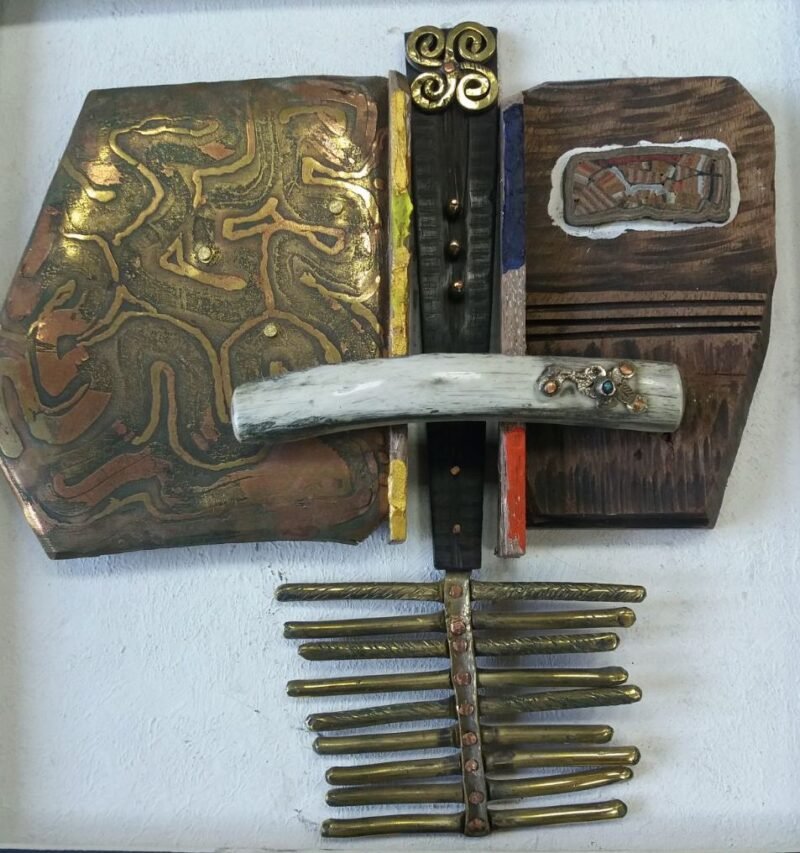

Dilmurod Sharipov (Dushanbe, Tajikistan) was born in Gissar. In 2003, he graduated from the M. Olimov Art College and became a jeweller. Since then, he has been living and working in Dushanbe and actively participating in international festivals and fairs.

The jeweller prefers layering in his modern jewellery and uses different materials: silver, copper, wood, brass, melchior, and all kinds of natural stones in which Tajikistan is so rich.

According to Dilmurad, all the stones and metals he uses are “from the depths of Tajikistan”. His Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/Dilmurod84) features his work, most of which is fancy “European” jewellery. According to him, he also recreates old Tajik jewellery “so others can see and know what our ancestors wore.”

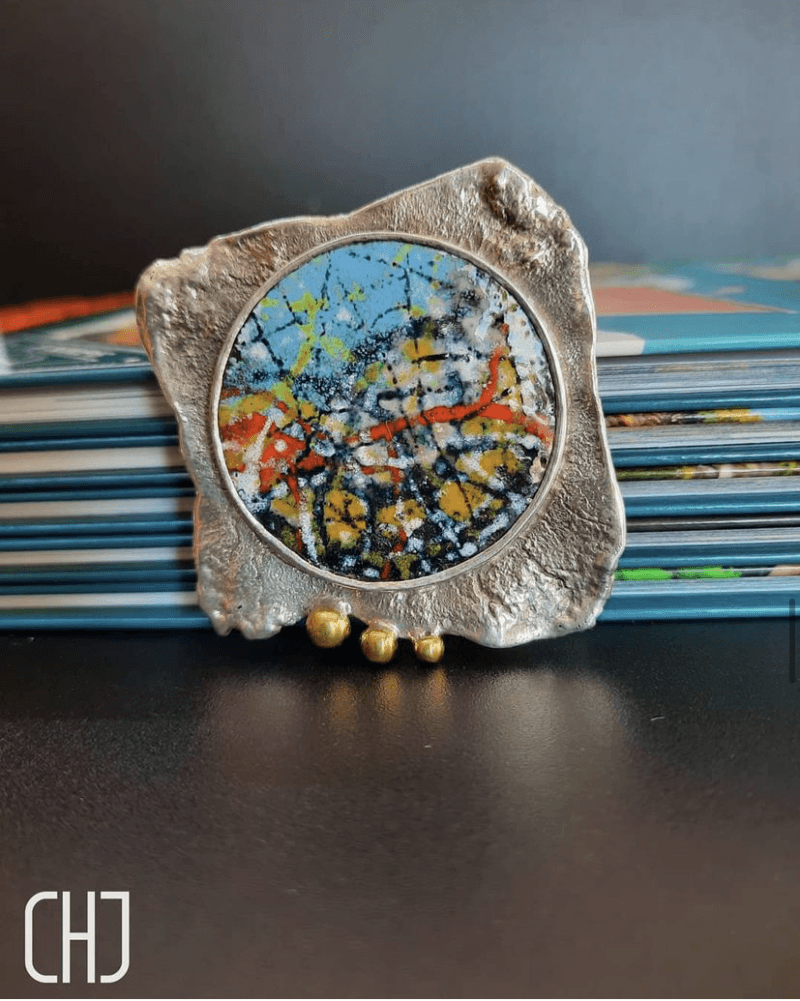

Serzhan Bashirov (Nursultan, Kazakhstan) comes from the East Kazakhstan region. There were no jewellers in his family, although his grandmother was famous for her skill at making traditional Kazakh headgear and fur coats from fox and wolf skins.

Serzhan studied artistic metalwork at the Almaty Art School in the 1980s and later learned sculpture at the Almaty Theater and Art Institute.

His jewellery installations struck a chord with me when I met him in 2019 at an exhibition of Kazakh artisans in Washington, DC. Preferring to work with silver, carnelian, and turquoise, Serzhan combines “native” materials and the techniques of the masters of bygone centuries into new forms. In this process, he deploys a number of what he calls “folk techniques” — notching, forging, riveting, etc. — as well as more sophisticated approaches like scanning, enamel, and grain.

As the jeweller points out, kapsyrma / kaptyrma (silver clasps with hook and loop) and shashpau / sholpa (ornaments for braids) from the last century are now made extremely rarely and exclusively on order. However, even in the 19th Century, when these ornaments were popular, they were made mainly on order (although in the first half of the 20th Century, craftsmen began to sell their products in the bazaar).

Sadly, the jewellery that richly decorated Kazakhs in earlier times has ceased to be a part of everyday life and is now confined mainly to museum collections. Serzhan Bashirov’s Instagram page is https://www.instagram.com/serzhankz/?hl=ru.

Zhakshylyk Chentemirov (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan) is originally from the Issyk-Kul region. There were no jewellers in his family, though his father was a talented woodcarver. Zhakshylyk always loved to draw, so after school, he joined an art school in Bishkek. Since then, he has lived and worked in Bishkek.

He works mainly with silver, turquoise, coral, pearls, wood, and bone. All materials can be bought in a specialized store; some customers bring their own stones and precious metals. Sometimes customers ask to melt their jewellery down into new pieces, although the old jewellery usually has extremely low silver content.

Zhakshylyk has experience making antique jewellery such as earrings, pendants, etc., but does not hide the fact that it is not easy to recreate such jewellery, which is done with the aid of photos.

As Zhakshylyk does not like to copy others’ works and prefers to create his own masterpieces, his jewellery works, which are very popular among tourists and locals, differ from traditional forms and feature new designs. He uses old techniques that existed in the region. Among the techniques that he “does not use much” are grains and filigree: significantly, the jewellers of Northern Kyrgyzstan never liked the latter, whereas it was widespread in the South.

A curious series of his jewellery for weddings is called Kyzga Sep (bride’s dowry). This kind of jewellery, while not reproducing the traditional forms, supports a dowry, one of the traditional wedding rituals.

More of Zhakshylyk’s jewellery can be seen on his Instagram page at: https://www.instagram.com/chentemirovzhakshylyk/?hl=en.

A very honourable profession among Turkmens, a jeweller was traditionally considered a man’s profession. In modern Turkmenistan, women are also becoming jewellers. Ogulgerek Myradova (Ashgabat, Turkmenistan) was trained as a jeweller at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Ashgabat. After graduating from the Academy, Ogulgerek continued her work there. She is also a member of the Union of Artists of Turkmenistan. There were no jewellers in her family, but her father is Mukhammet Yazyev, a famous Turkmen artist.

Ogulgerek creates jewellery together with her husband, Shohrat Myradov, a fellow graduate of the State Academy of Fine Arts. They create fantasy jewellery based on their own sketches, but most of all, they are fascinated with creating Turkmen jewellery “in the national style.”

Ogulgerek and Shohrat explore old masterpieces through printed and visual sources, as well as by looking at antique jewellery in Turkmen museums. They prefer silver (traditionally a thin layer of gold is applied to the silver pattern), carnelian, turquoise, zirconia, chrysoprase, chrysolite, and black agate.

They have mastered the traditional Turkmen jewellery techniques of past centuries, but also develop new ones: for example, engraving and stamping were historically widely used by Turkmen jewellers, while filigree was less common. Both jewellers use engraving and stamping for traditional jewellery, while filigree is widely used in modern-type jewellery.

“It was impossible to imagine a Turkmen woman or girl dressed in the national costume without silver jewellery,” reported Soviet ethnographer Galina Vasileva in 1973.

In 2021, Turkmen women, like women from other Central Asian countries, continue to wear traditional jewellery.

This review does not include the jewellery art and masterpieces of Karakalpaks, Uighurs, Arabs, Jews, and other ethnic groups from Central Asia. Yet even this short overview demonstrates several important points.

Changes in jewellery production are constantly occurring due to social, political and economic transformations, even if traditional forms remain comparatively stable. Artisans are interested in creating a new type of jewellery; clients/customers from Central Asia support this with continued demand for the jewellery of modern design.

Some vintage jewelry forms are already disappearing, but not everywhere. In Turkmenistan, one can find an abundance of jewellery that is similar in form and design to that of earlier centuries. Such jewelry masterpieces are especially obligatory for a bride: silver ornaments make the bride’s costume heavy and solemn.

The preserved tilla-kosh and jewellery sets included in kyzga sep (dowry) reveal that some traditional forms (or their echoes) have been preserved not only in Turkmenistan but also in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Thus, wedding traditions seem to protect Central Asian jewellery from extinction.

Just as it was centuries ago, today’s Central Asian jewellery is diverse, with the jewelry of Kyrgyz masters differing from that of their Turkmen and Uzbek counterparts, although the contemporary jewellery of Kazakh and Kyrgyz masters may overlap. Local differences are now significantly blurred, but some jewelry techniques continue to be preserved and developed where they were practiced before. Further research into the jewelry art of the region would be valuable.

This feature was first published in the Voices on Central Asia

Bibliography:

Fahretdinova Deliara. Iuvelirnoe iskusstvo Uzbekistana. Tashkent, 1983.

Sukhareva, Ol’ga. Pozdnefeodal’nyj gorod Bukhara. Tashkent, 1962.

Vasil’eva, Galina. “Turkmenskie zhenskie ukrasheniia.” Sovetskaiia Ethnografiia 3 (1973): 90-98.

The author would like to thank every jeweler who kindly agreed to be interviewed and talk about their jewelry art and practices.

Snezhana Atanova is a research fellow at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Science (Moscow), associated researcher at the French Institute for Central Asian Studies (IFEAC). She researches the material culture and cultural heritage of Central Asia with reference to anthropology, archaeology, and history.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia