By Israruddin Israr

As Gilgit-Baltistan continues to navigate the delicate balance between tradition and modernity, a return to its indigenous systems of governance may offer the most grounded and sustainable path forward. This sentiment resonated strongly during a recent seminar and workshop in Hunza, where participants called for the revival, modernisation, and institutionalization of customary laws as the cornerstone of local governance.

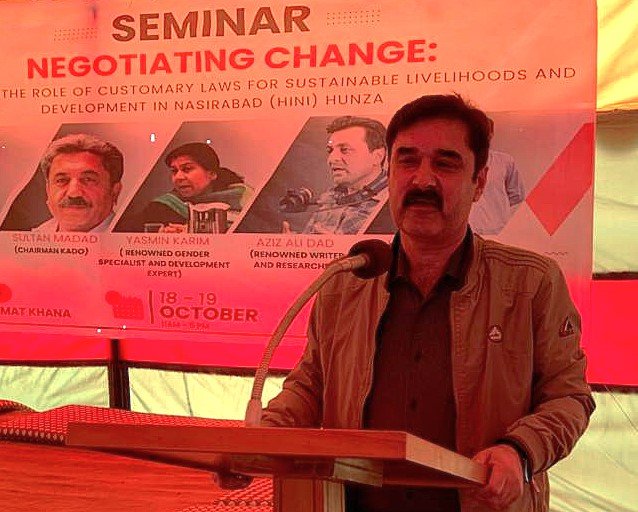

The two-day event, held on October 18–19 in Nasirabad (Hini), brought together scholars, community leaders, and activists who argued that reconnecting with these time-tested practices is essential for ensuring social harmony, environmental stewardship, and inclusive development in the region.

Jointly organised by two youth-led organisations — the Nasirabad Students Helping Association Karachi (Nashak) and Nasirabad Youth — the event aimed to initiate dialogue on customary laws, the challenges of governance and sustainable development in Hini (Hunza), in particular, and across Gilgit-Baltistan, in general, and to recommend solutions based on the indigenous wisdom.

For me, it was an honour to moderate and facilitate the event titled “Negotiating Change: Recognising the Role of Customary Laws for Sustainable Livelihoods and Development.”

A diverse panel of experts, including Aziz Ali Dad, a noted social thinker, and author; Baba Jan, a renowned political leader; Sultan Madad, an intellectual and community activist; Yasmin Kareem, a noted gender and development expert; and Jafar Nazir, a young researcher from Punial a researcher, and Jahan Zeb an energy expert and social activist, discussed governance challenges in the region. They highlighted the importance of revitalising customary laws to meet today’s environmental and social needs.

Discussants during the workshop and the seminar highlighted deep ambiguities, flaws in the existing governance system and gaps that often lead to community-level conflicts.

They were in unison in emphasising that these issues could be addressed by syncronising and harmonising customary and contemporary laws, enabling peaceful conflict resolution rooted in local wisdom.

One of the most urgent concerns raised by the participants was the suspension of local government bodies in Gilgit-Baltistan for thr lsdt over 20 years. With no LB elections held since 2004, communities have been left without formal representation or mechanisms to resolve local disputes. Local body elections, they urged, must be held without delay, and decision-making powers devolved to institutions that reflect community realities rather than distant bureaucratic structures.

They questioned the powers, scope, and effectiveness of Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly and emphasised that it should confine itself to legislations, while governance at the grassroots level must remain in the hands of the local bodies, guided by time-tested customs, democratic participation, and social inclusivity.

The participants also criticised the Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly for misusing development funds and failing to legislate on key regional issues such as tourism regulation, environmental protection, and land rights.

Two distinguished researchers and social thinkers presented insightful papers that anchored the discussion in historical and analytical context. They laid the groundwork for deep reflection on how traditional legal and moral systems might be integrated into contemporary village management and policy-making.

Aziz Ali-Dad, an eminent social thinker and author, in his presentation on “Negotiating Change: Recognizing the Role of Customary Laws for Sustainable Livelihoods and Development in Hunza.” argued that indigenous governance systems, if updated democratically, could serve as robust frameworks for sustainable development and social justice such as land banking system.

He cited concepts such as community-based land banking as examples of how traditional systems can be adapted for modern needs.

Jafar Nazir, a researcher and educationist, shared a detailed case study on the customary laws of Punial, a former princely state of Gilgit-Baltistan. His work illustrated how traditional governance systems had maintained social order and balance for centuries, providing lessons for present-day Hunza.

Sultan Madad, Chairman, the Karakoram Area Development Organization (KADO), who chaired the event in his opening remarks reminded the participants that customary laws have long served as the backbone of communal life in Hunza and across Gilgit-Baltistan.

He emphasised the urgent need to revive, update, and institutionalise these laws in a way that aligns with modern realities. His words set a reflective tone, calling on the community to rediscover its own systems of governance and justice.

A strong emphasis was placed on empowering women in all village-level decision-making bodies, including the Numberdars, Jirga, and water and other local resource management committees, income generation, and conflict resolution. Participants agreed that this is essential for achieving social balance and sustainable community development. Vulnerable groups such as persons with disabilities, elders, and children will also be included in all community institutions.

Their message was laud and clear: the region cannot move toward sustainable development without empowering local communities and recognising the enduring value of their indigenous wisdom and governance systems.

In essence, the seminar served as both a reminder of the wisdom embedded in local traditions and a roadmap for how these can inform modern governance in ways that are just, participatory, and sustainable.

As moderator, I encouraged the panelists and audience to reflect on our indigenous problem-solving methods how elders once mediated disputes with fairness and how such practices can still guide us today. It was inspiring to see local wisdom and academic insight come together in a shared vision for the future.

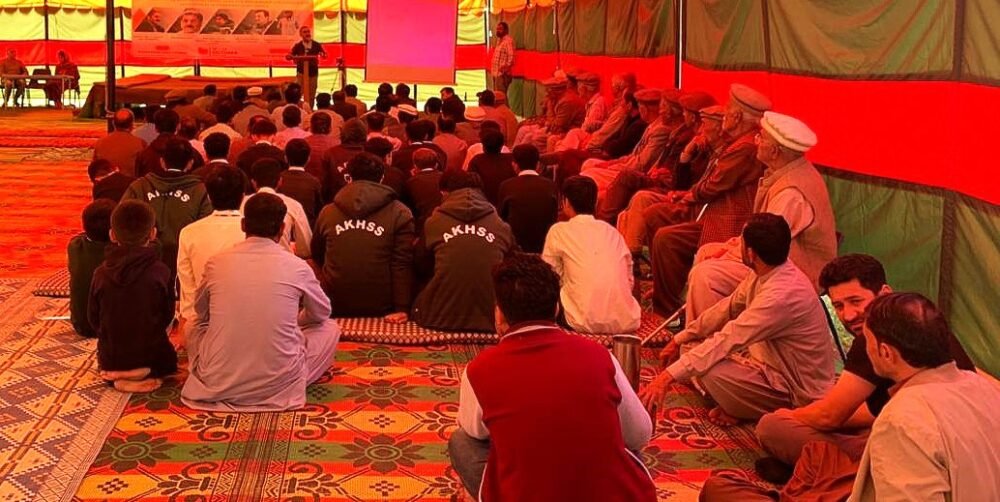

The second day of the event focused on interactive group discussion. The participants were divided into four groups representing civil society, AKDN and financial institutions, and political parties to explore the roles, strengths, resources, challenges, and future pathways for the community.

Through open dialogue and collective reflection, the participants identified several key priorities. It was agreed that all discussions would be transcribed and compiled into a ‘Village Model Development Plan’, rooted in local needs and endorsed by the wider community.

The model aims to adapt customary laws to address emerging challenges, including responsible tourism, environmental protection, land management, and external investments, while ensuring community ownership and accountability.

The abolition of the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR) has created a legal vacuum that remains unaddressed by any effective governance system. Once central to community order, customary laws have been neglected. Participants agreed that reviving and democratizing these traditional systems is essential for restoring accountability and stability at the grassroots level.

This seminar marked a turning point for Nasirabad, bringing together the entire community, elders, youth, women, and professionals, to discuss their collective future.

For the first time, such a dialogue was held by the people of Gilgit-Baltistan, for the people, ensuring that every stakeholder’s voice was heard. Unlike externally imposed models of the past, this initiative emerged organically from within the community.

The organizers deserve recognition for initiating this much-needed dialogue on complex regional issues and for setting an example that other communities across Gilgit-Baltistan can follow. Reviving and modernising our customary laws represents a return to the sustainable, participatory, and self-reliant systems that once made our villages thrive.

As I reflected at the close of the workshop, I realised that if we can harmonise our ancestral wisdom with democratic practices, we can rebuild governance from the ground up, ensuring that our people remain the rightful stewards of their land, resources, and destiny.

Israruddin Israr is a Gilgit-based human rights activist, columnist and campaigner for the empowerment of vulnerable segments and local communities in Gilgit-Baltistan. He contributes essays and comment pieces on social and human rights issues to The High Asia Herald and Baam-e-Jahan Pages.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia