Nestled at the confluence of the Pamir, Karakoram, Hindu Kush-Himalaya, and Sarikol ranges, lies an emblem of valleys that is home to one of the last bastions of ancient Iranian mountain culture. Vernacular architecture of the lesser-known High Asia region, or “Roof of the World” is a fundamental expression of human creativity, reflecting the cultural and historical spirit of its people. Its study provides invaluable insight into the ethnic identity, spiritual life and economic conditions of the communities living in the region.

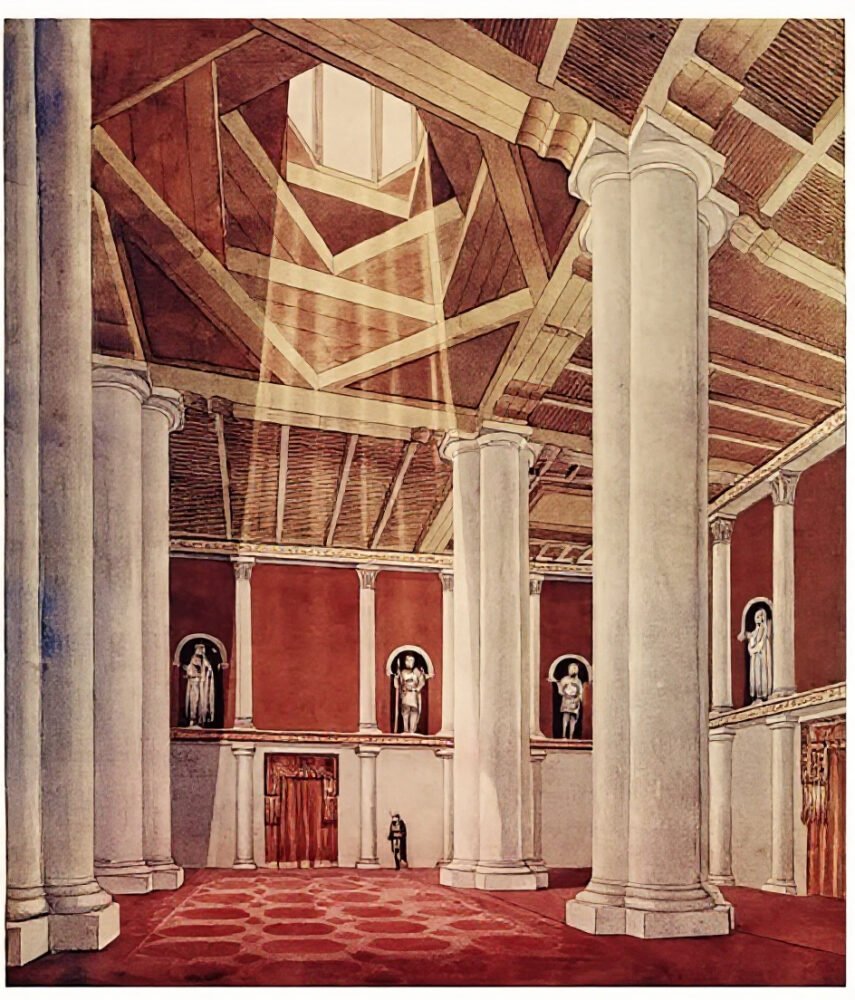

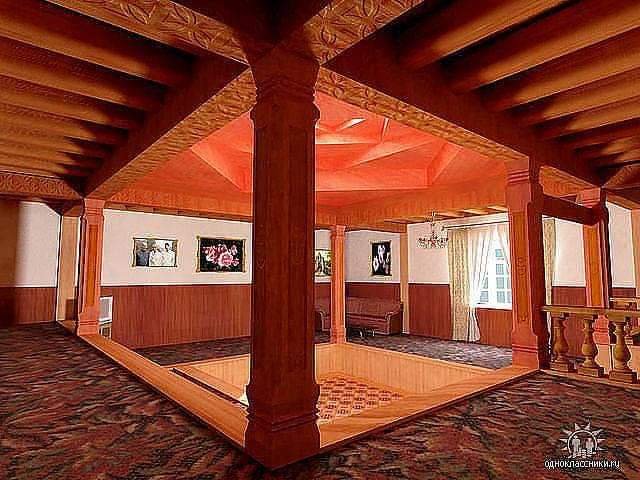

From the caisson ceiling often in a layered, square-on-square pattern with five-column house and the stone fortresses to the carved wooden mansions and the tower-palaces, this culturally cohesive region developed a vernacular architecture that represents a remarkable adaptation to isolation, scarcity of resources, altitude, and spiritual symbolism. These were multifunctional structures serving simultaneously as places of worship, cosmological diagram, family residences and defensive strongholds.

Despite differences in belief systems and modern political boundaries, the entire region shares a common architectural lineage, a legacy traceable to the Bronze and Iron Ages. The Pamiri architecture is found Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) of Tajikistan, Badakhshan and Wakhan (Afghanistan), Tashkurgan County (China), Gilgit, Hunza, Ghizer Diamer (Gilgit-Baltistan) and in southern India. Pamiri architectural parallels are found in ancient Bactria and Greece as well as in South Caucasus, Asia Minor, Lower Volga, Trans-Ural, Northern Kazakhstan, Western Siberia, Georgia, Armenia, and Kurdistan.

The ancient cave temples of Mogao, Dunhuang, Wenjushan, Gansu, the Bingling Temple, Yongjing, Yungang, Xinjiang and Kizil in China, the Bamiyan Cave Temple in Afghanistan and a monastery ruin near the Great Stupa of Sanchi in India also exhibit similar architectural features of Chorkhona (square-on-square) skylight.

Hypothetically of Vedic-Aryan origin, this vast tradition spread across half the world, largely due to its transmission along the Silk Road. The scholarly record of this vernacular architecture can be divided into five phases such as Chinese pilgrims and Imperial envoys (7th-17th CE), Medieval Muslim travellers (10th-19th CE), the ‘Great Game’ and early ethnography (19th-20th CE), Soviet ethnography (20th CE), post-colonial and contemporary human geography (1950s-present).

The earliest written records of the region date back to the 7th Century, provided by Chinese pilgrims and officials who crossed the “Onion Mountains,” as well as by Persian and Arab geographers. For instance, the Chinese monk Xuanzang (646-648 CE) described the kingdoms of Sarikol, Shughnan, and Wakhan, noting their wood and stone structures built on steep slopes, which featured watchtowers and flat roofs.

A few years later, Korean monk Hui Chao provided what is considered the first known description of the classic Wakhi single-room residence with its distinctive square roof opening, known as a Chorkhona. Later accounts, such as those by Chand De (1259) and the Ming Tribute expeditions (1410s-1530s), recorded nearly identical features, noting the four strong poplar columns, the wooden square-on-square skylight, and a central, raised fireplace. These records have been preserved in various Chinese gazetteers.

Medieval Muslim scholars offer complementary perspectives. For instance, al-Biruni (973-1050) described the fortified settlements (Qal’a) and fire rituals of Bolor. Similarly, the Baburnama (1530s) provides the first detailed portraits of flat-roofed Sarikoli houses and the stone fortresses of Tashkurgan.

Sir Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-born British explorer, traversed the Sarikol and Pamir ranges four times between 1900 and 1930 in search of the ancient Silk Road. His expeditions produced the first comprehensive architectural records and photographs of the region’s vernacular architecture. Stein’s detailed photography and descriptions of Wakhi Qal’as, Pamiri watchtowers, and the planned fortresses of Tashkurgan provide modern confirmation of this fascinating structure. Moreover, he posits a direct architectural connection to the Kushan and early medieval periods (Stein 1907, 1921, 1928).

Due to the region’s geopolitical and strategic importance and the Anglo-Russian rivalry, a constant wave of systematic exploration began. With the advent of this new era, called as the ‘Great Game’, or ‘Game of the Shadows’ the work of John Wood (1838), Ole Olufsen (1896-99), Francis Younghusband and numerous Russian surveyors including Captain Grombchevsky on the northern slopes; George Scott Robertson’s photography of eight-storey carved wooden mansions in Kafiristan on the South (1896) are also vivid eyewitness accounts.

According to scholars, the four-column Sarikoli/Wakhi and five-column Rushani/Shughnani house constitutes a complete Zoroastrian-Ismaili cosmological framework.

After the demarcation of Durand Line and making of Wakhan Corridor, Soviet scholars like Alla Pisarchik, L.F. Monogarova, V.V. Bartold, V.A. Zhukovsky, A.A. Semenov, M.S. Andreev, I.I. Zarubin, N.A. Kislyakov, Yakubovsky, O.G. Bolshakov, N.N. Negmatov, A. M. Belenitsky, E. V. Zeimal, B. I. Marshak, A. I. Mandelstam, A. Dzhalilov, A. I. Isakov, V. A. Shishkin, S. G. Khmelnitsky, B. A. Litvinsky, V. S. Soloviev, V.V. Radlov, N.A. Aristov, A.I. Maksheev, A.V. Bunyakovsky, M.A. Terentyev, E.S. Smirnov, A. Shishov, M. Nalivkin, P. Maev, A.P. Khoroshkhin, N.P. Ostroumov, A.I. Dobrosmyslov, N.S. Lykoshin, and I.M. Mukhitdinov, among many others, produced a substantial work spanning over half a century since 1920s.

According to these scholars, the four-column Sarikoli/Wakhi and five-column Rushani/Shughnani house constitutes a complete Zoroastrian-Ismaili cosmological framework. Subsequent expeditions by Danish, German, Austrian, and Italian explorers and geographers, led by figures like Edelberg, Klimburg, Cacopardo, and Jettmar, documented similar carved palaces throughout the Hindu Kush. Remarkably, many of these structures are still in ritual use, as seen in the cultures of Kalasha and Nuristan.

German geographer Hermann Kreutzmann’s work can be seen as the most comprehensive modern survey in Gorno-Badakhshan, the Pamir, Wakhan, Gilgit-Baltistan, and Tashkurgan since the 1980s. The post-1990 collapse of traditional practices in Gorno-Badakhshan and Tashkurgan is starkly evident from his repeat-photography studies of their vernacular settlements.

Hermann’s research suggests that less than five percent of the original architecture survives in an unaltered state. The exceptions are regions like Sarikol, Wakhan, Gojal, Ishkoman, and Broghel, where many families maintain a single ceremonial room, preserving a continuum of traditional practices.

Despite the pressures of change and modernisation, substantial preservation efforts are underway in these regions. Notable examples are the efforts of Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), which has restored historic forts in regions from Tajikistan’s Gorno-Badakhshan to Gilgit-Baltistan’s Hunza District, Khaplu and Shigar districts; Chinese ethnographic documentation; UNESCO’s work in Nuristan; and archaeological projects in the Kalash Valley.

These efforts provide hope that this unique knowledge will survive, even as the physical structures and building traditions themselves fade. This momentum is further augmented by Tajikistan, which has launched a state-sponsored programme specifically dedicated to reviving this historical and cultural heritage, particularly its vernacular housing traditions, for practical application.

Contemporary renditions of this alluring architecture can be seen in the Ismaili Center of Houston (USA), the Ismaili Jama’at Khana in Khorog (Tajikistan), AKESP’s Higher Secondary School in Gilgit, Kalasha Dur Museum in Bamboret, and many more buildings across the globe. Yet, only fragments of this marvel of humankind’s most remarkable domestic tradition survive in daily use today.

From the first recorded glimpse of a smoke-hole in a roof by Chinese pilgrims to the last carved columns still standing in Sarikol, Nuristan, Gojal-Hunza, Kalasha, Broghil and Wakhan, the mountain architecture of High Asia, Central Asia and Eastern Iranian region has been continuously observed and documented for over fourteen centuries. This miniature model of the universe still speaks to us quietly of the columns that hold up both the cosmos and the roof, of the sacred fire that must never perish, and of the families who continue to live within its magnificence.

Dr Zahid Usman is a multi-disciplinary practitioner and educator from Swat Valley. His work as an architect, urban and regional planner, and lighting designer is grounded in spatial planning, large-scale master planning, heritage conservation, infrastructure development, and community development. He is dedicated to developing integrated solutions that balance socio-economic, environmental, and cultural factors. A graduate of the National College of Arts (NCA) Lahore, University College Borås, KTH Stockholm, and International Islamic University Malaysia, Usman now teaches at his Alma mater, the NCA, and maintains an active research agenda focused on mountain heritage. He can be reached at: xahidusman@gmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia

One thought on “Scholarly journeys through High Asia’s vernacular architecture”

An excellent article, written, composed, and well-articulated by Dr. Zahid Usman. This article provides deep insights from a traditional architectural realm, highlighting the significance of architecture through an incredible thought process. The golden age of Scholars takes us on a breathtaking journey through time.