German scholar’s latest book explores new aspects of history, culture and politics of ‘Great Game’ and expansionist designs of colonial powers in High Asia

By Aziz Ali Dad

A new book sheds light on the politics of ‘Great Game’ and expansionist designs of colonial powers of the 20th century in High Asia and Central Asia from new perspectives based on different sources.

A new book sheds light on the politics of ‘Great Game’ and expansionist designs of colonial powers of the 20th century in High Asia and Central Asia from new perspectives based on different sources.

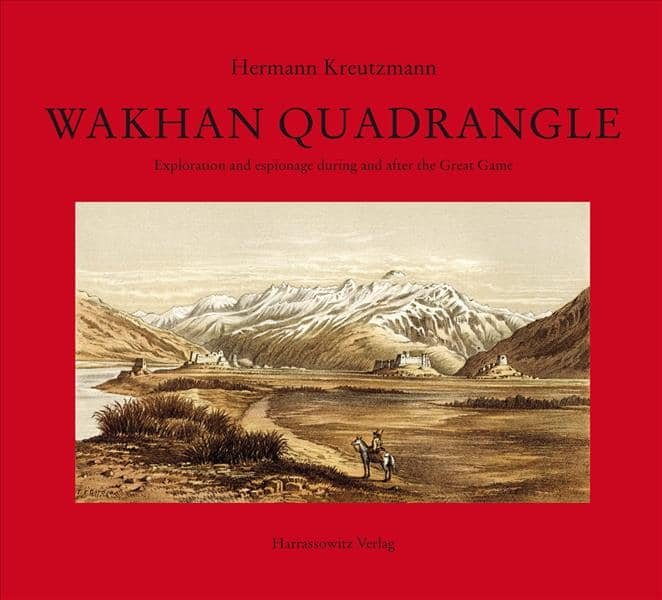

The book Wakhan Quadrangle – Exploration and espionage during and after the Great Game by Dr Hermann Kreutzmann also explores new aspects of the history, culture and politics by employing wide array of sources ranging from researchers, geographers, officials, literature, explorers, travellers, indigenous knowledge, authors, knowledgeable pathfinders, translators, spies, merchants, missionaries, map-makers, storytellers, local historians, bazaar dwellers etc., in the High Asia region without acknowledging them.

The wide range of sources of his research enables Professor Hermann to achieve a comprehensive understanding of the theme. To understand the dynamics of the Great Game, and the role of actors and players in the gamble, he takes into consideration asymmetric power relations and its impact on the perception of actors. He clearly keeps the power equation in the heart of his research about the multiplicity of actors and factors that turn a relatively isolated region of Wakhan into a quadrangle.

Dr Hermann, who is a professor of Human Geography; Director, Centre for Development Studies; Director, Institute of Geographic Sciences, at Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, shared his vast knowledge and experience about High Asia at a gathering at my home.

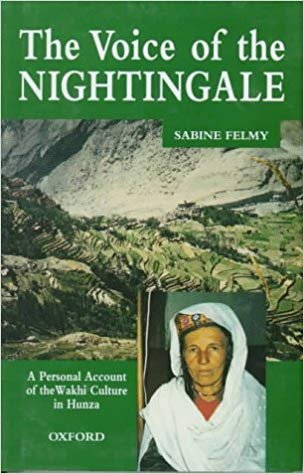

His wife Sabine Felmy is also accompanying him in his research tour of Gilgit, Ghizer, and Hunza. Sabine has written a book The Voice of the Nightingale: A personal account of the Wakhi culture in Hunza after living among the community for several years, studying their history and oral traditions. Her descriptions of recent developments in the Karakoram provides unique insights into the changing Wakhi culture.

Prof Hermann has propelled the region of Gilgit-Baltistan into the international academic domain. In his writings, he also challenges us to rethink about our old prejudices and fictional view of history that we take as knowledge. His new book Wakhan Quadrangle is the result of 10 years’ research using for the first time Russian sources about the region.

Prof Hermann has propelled the region of Gilgit-Baltistan into the international academic domain. In his writings, he also challenges us to rethink about our old prejudices and fictional view of history that we take as knowledge. His new book Wakhan Quadrangle is the result of 10 years’ research using for the first time Russian sources about the region.

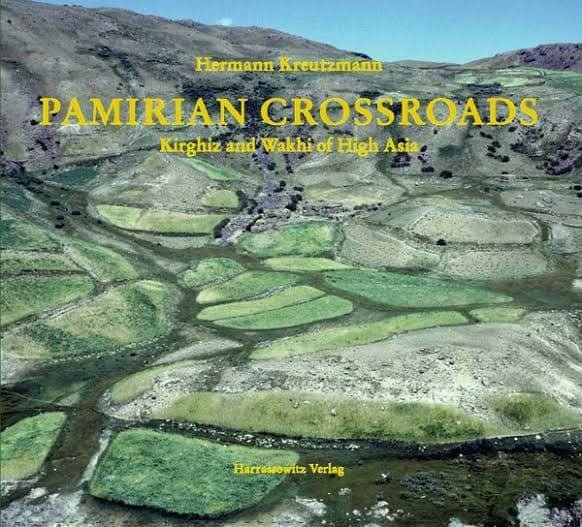

The book is a follow-up volume to Pamirian Crossroads: Kirghiz and Wakhi of High Asia which was work of 30 years of research. Dr Hermann’s book looks at the politics of the ‘Great Game’ from multiple lenses and perspectives coming from his sources. Normally in the Subcontinental scholarship, High Asia is not only the region at the fringes of the mainland in terms of geography but also in scholarship. Even when ‘Great Game’ is discussed, it is viewed through the scholarship produced by scholars and researchers serving the British colonial empire. Dr Kruzmann has managed to escape the straight-jacket of colonial sources by employing local, literary, Chinese and Russian sources.

Mapping of unknown territories was a daunting task and activity during ‘Great Game’. Its maps on the pages open the ways to access the inaccessible regions of High Asia. Dr Kruzmann provides maps charted by Russian and British empires and also of Chinese.

What makes the book interesting is the employment of literary sources to read political thoughts and strategies. Two chapters precede his text which aims at contextualising his report and present the state of affairs in knowledge gathering prior to his journey. The text is framed with reflections about his colonial masterminds, the ‘singers of the empire’ — Rudyard Kipling and Fyodor Dostoevsky — the conflict of interests among state and actors. For example, Dostoevsky is normally seen as a giant of Russia literature and a great novelist who explores existential dilemmas of his protagonists. The book presents his political position about the expansion of the Russian empire in Central Asia. Dostoevsky favours Russian conquest of Central Asia. He compares Russian colonial expansion into Central Asia with the European conquest of North America.

According to Hermann the new book is “concerned with the aspect of knowledge-gathering in a colonial and geopolitical hotspot — the Wakhan Quadrangle — which is presently shared between Afghanistan, China, Pakistan, and Tajikistan.”

In the 282-page book he has investigated and analysed the symbiosis of exploration and spying during the ‘Great Game’ under the pretext of asymmetric socio-political relationships and an unequal appreciation of knowledge-gathering when it comes to its actors either Europeans or Asians. The local knowledge-producers have often acknowledged only under their pseudo names and generally termed as ‘native explorers’.

His use of local sources in the book provides in-depth insight into the indigenous perspective towards political changes in the ‘Great Game’. For instance, the use of a neglected book of Munshi Abdul Rahim who traveled in different regions of High Asia from 1879 to 1880 provides interfering perspective about the region. To contextualise his reading and retrace steps of Munshi Abdul Rahim Professor Hermann has traveled to Badakhshan, Wakhan, and Gilgit during the last four decades.

“I was fortunate to be able to retrace all steps and routes of Munshi Abdul Rahim in Badakhshan, Wakhan, Chitral, Yasin, Ghizer and Gilgit during various journeys and fieldwork campaigns spanning a stretch of four decades that have allowed me as well to visit neighbouring regions,” puts the author. Munshi Abdul Rahim was a spy who travelled to Wakhan and Badakshan via Gilgit crossing Darkut pass in Yasin. Rahim sent accounts of his travels in Gilgit, Wakhan and Badakshan in his letters and reports to colonial officers. Hermann seems to contend that colonial officers including John Biddulph used his reports. Hermann in this book provides details of the context. More importantly, Hermann in his book has provided facsimile of Munshi Abdul Rahim’s book Journey to Badakshan with report on Badakshan and Wakhan, published in 1885 by F.D. Press, Simla.

“I was fortunate to be able to retrace all steps and routes of Munshi Abdul Rahim in Badakhshan, Wakhan, Chitral, Yasin, Ghizer and Gilgit during various journeys and fieldwork campaigns spanning a stretch of four decades that have allowed me as well to visit neighbouring regions,” puts the author. Munshi Abdul Rahim was a spy who travelled to Wakhan and Badakshan via Gilgit crossing Darkut pass in Yasin. Rahim sent accounts of his travels in Gilgit, Wakhan and Badakshan in his letters and reports to colonial officers. Hermann seems to contend that colonial officers including John Biddulph used his reports. Hermann in this book provides details of the context. More importantly, Hermann in his book has provided facsimile of Munshi Abdul Rahim’s book Journey to Badakshan with report on Badakshan and Wakhan, published in 1885 by F.D. Press, Simla.

Two more extensive chapters follow his text in presenting the after-effects of boundary-making, exploration and external interventions in a remote though geo-politically important mountain region of High Asia and its inhabitants. The route of Munshi Abdul Rahim is illustrated with a variety of historical maps, photographs and sketches covering the whole itinerary, and it was attempted to show the contemporary state of affairs in Badakhshan and Wakhan. All places and routes he visited were personally looked at by the author and illustrated with images from successive explorers and travelers.

The book provides rich Information and deep knowledge about politics of boundary making and intervention of great powers into the remote regions of High Asia. It resulted in turning off the hitherto isolated region into the turf for the game of the then colonial powers. The topics covered in his report are interpreted on the basis of contemporary archival resources.

The final chapters reflect on the contributions from expeditions and missions to academic knowledge production and decision-making.

Among his numerous books The Karakoram in Transition: Culture, Development, and Ecology in the Hunza Valley, Sharing Water: Irri gation and Water Management in the Hindukush-Karakoram-Himalaya and Pastoral Practices in High Asia and Mapping the Transition in Pamirs are significant.

gation and Water Management in the Hindukush-Karakoram-Himalaya and Pastoral Practices in High Asia and Mapping the Transition in Pamirs are significant.

Professor Hermann enacted a pivotal role in the preparation and compilation of the 12-volume Culture Area Karakorum Scientific Studies series. It is a compendium of knowledge related to high mountains of the Karakorum, Hindukush, and the Himalayas, in Pakistan and in the adjoining countries. For the youth of Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral, his books are invaluable sources to situate the history of the region in broader historical and regional context. He is a great mentor and friend. During my sojourn to Berlin for fellowship, he opened his vast library for me and gifted Pamirian Crossroads.

Hermann’s scholarship combines rigorous research methodology and sources with extensive fieldwork. He literally knows the regions and valleys like the back of his hand. Besides deep insight into the history of politics and rich information, Wakhan Quadrangle gives lessons for researchers in Pakistan. That is tenacity of purpose, attention to details and corralling operating findings of research and reading with extensive fieldwork. Unfortunately, we in Pakistan lack all these qualities. Even if we have the first two qualities we never bother to spend time in the field. Hence, we tend to produce opinionated knowledge instead of explorative knowledge.

Aziz Ali Dad is a social scientist with a background in philosophy and social science.

Aziz Ali Dad is a social scientist with a background in philosophy and social science.

Email: azizalidad@gmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia