It’s only just the start of the summer mountaineering season in the Himalayas and the Karakoram and already our Pakistani climbers have made us proud. On May 14, Sirbaz Khan became the first Pakistani to ever summit Lhotse in Nepal. At 8,516m it’s the fourth highest mountain in the world.

This 32-year-old budding mountaineer from Aliabad, Hunza in Gilgit Baltistan only started climbing just three years ago in 2016. He was inspired from a trek he did to the K2 basecamp in 2004. “It was the golden jubilee year of the first K2 summit,” he says. (Italian climbers Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni did the first successful summit of the K2 via the Abruzzi Spur on 31 July 1954.) He was speaking to me over the phone from the airport in Kathmandu, waiting for the flight that will bring him back to Pakistan.

He then started working on guiding trekkers and working as a crew member for various mountaineering teams until he finally decided to scale his first big mountain peak. “I did my proper climbing — professional climbing — from 2016,” he relates. “My first attempt at climbing a big mountain was the K2 but we were unsuccessful. Our Camp Three was totally destroyed. So, all of us climbers decided to end our climbs and descend.

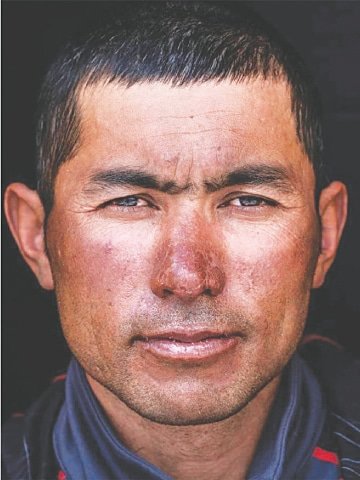

Pakistani mountaineer Sirbaz Khan only began climbing in 2016. Now he has summitted the fourth highest mountain in the world sans supplemental oxygen. He is dreaming of climbing all 14 peaks above 8,000 m without oxygen

“I tried again in 2017 with Nazir Sabir Expeditions but we were unsuccessful due to bad weather and deep snow. But the same year in autumn, I made an attempt to summit the Nanga Parbat. It was my first attempt on the Nanga Parbat and we were successful.”

His Nanga Parbat summit was during the more unconventional autumn season. “People have attempted it before in autumn, but they had not been successful. Then, I finally summited the K2 in the summer of 2018.

“It’s just kismet that I started my career with 8,000m mountains instead of smaller ones,” he adds. “People usually leave the Nanga Parbat and K2 for the very end, whereas I started with the two most difficult [8,000m] mountains. I’ve been very lucky.”

He did both of these summits without supplemental oxygen. Air begins to thin from 3,000m, where most people start to feel the altitude. Above 7,000m the air is so thin that it’s considered the death zone. There are very few climbers in the world, from the already tiny community of big mountain climbers, that push their bodies to their very limits by climbing to these heights without supplemental oxygen.

Why is he so opposed to using supplemental oxygen? “Because with oxygen anyone can do it. Even you!” he laughs. I would like to add here that while it might make climbing easier, but that’s blatantly untrue.

“I have a mission,” adds Sirbaz. “It’s a dream. I want to be the first Pakistani to have summited all 14 8,000m peaks without oxygen. This is my third consecutive successful attempt on an 8,000m mountain.”

But summiting Lhotse wasn’t neccessasily part of his original plan. Sirbaz had his eyes set on Everest.

“Whatever the conditions are now,” he says referring to commercialisation of Everest, “it’s still the world’s tallest mountain.” The ‘conditions’ he is talking about are where mountaineering companies market expeditions to even the most amateur of climbers with their guides and Sherpas almost pulling them up to the summit. He mentions having seen Sherpa guides on both sides of their clients on a climb, holding their hands and sometimes even clipping and unclipping their client from the ropes themselves.

So how did he end up at Lhotse instead of Everest? “You have to work harder to acclimatise before climbing an 8,000m mountain without oxygen,” he says, referring to the climbs big mountaineers make — going up and down the mountain at various increasing altitudes so their bodies can adapt to the harsh, low air conditions until they finally make a bid for the summit. It’s hard enough for climbers that will use supplemental oxygen during the final push, according to Sirbaz, it’s even harder to acclimatise if you’re planning to make that push without any breathing aid.

“Everest is 8,848m and Lhotse is 8,516m,” he explained, “So, if you climb Lhotse first, you are already acclimatised for Everest. That’s why I climbed it first. So that climbing Everest without oxygen would be easier.”

Lhotse is also situated right next to Everest. “I would’ve just had to climb 300m because the Camp Four (the final camp before the summit bid of any 8,000m mountain) of both — Everest and Lhotse — is the same. But I got frostbite while climbing Lhotse, so I had to give up Everest — for now.”

How did he end up getting frostbite and how bad is it? “This year it was very cold in the Himalayas,” he says. “For the first time, casualties have been this high — around 20 climbers have died climbing Everest, Makalu, Lhotse and Kangchenjunga. Mostly because of how cold it was, they [the climbers] succumbed to hypothermia and there is low oxygen at that altitude as well.”

“In hindsight, I think if I had attempted Everest first, it would’ve posed as a greater problem for me,” he’s referring to the major delays caused by the traffic jam of climbers at the summit. Photos show a packed line of climbers across the routes trying to squeeze and edge their way up and down the summit. Deaths on Everest this year have been largely attributed to the slow pace caused by the jams, resulting in climbers being exposed to the cold and harsh conditions for far too long.

One Pakistani who was lucky and managed to finally get his Everest summit (on May 22) is Mirza Ali.

Along with his famous sister Samina Baig, the first Pakistani woman to climb Everest, they began their seven summits quest — to climb the highest peak in each continent — in 2013, starting with Everest. Samina managed to make it to the top, Mirza stayed back because of health issues. He’s been wanting to go back to Everest ever since. His success on Everest this year finally completes his seventh summit.

Did Sirbaz meet Mirza during his time in the Himalayas, considering Everest and Lhotse share the same basecamp? “Yes,” he said. “As I was returning from Lhotse and making my way back to basecamp, Mirza Ali had been making his way up to meet me. He had heard from our expedition leader that I had done the summit and perhaps he saw me as I came closer on my descent. He greeted me very warmly, took all of my gear and carried it to my tent at the basecamp himself. We had tea together. It was a wonderful welcome by a fellow countryman after such a climb.”

Soon after Sirbaz, another Pakistani summited Lhotse. Mohammad Ali Sadpara is now one of the most well-known mountaineers in Pakistan. He’s climbed all five 8,000m mountains in Pakistan and was a part of the first winter summit of the Nanga Parbat. He had travelled to Nepal to climb Makalu (8,485m), the fifth highest mountain in the world. Makalu is located 19km southeast of Everest, just on the border between Nepal and China.

He too didn’t originally plan to climb Lhotse and like Sirbaz, started his climb as a way to acclimatise his body for when he would climb Makalu. He made it to the top of Lhotse on May 17, three days after Sirbaz’s own historical summit. On May 24, Ali Sadpara also managed to summit Makalu. This makes Ali Sadpara the only Pakistani to have seven 8,000m mountain summits under his belt. That leaves seven more to go!

“He’s very senior to me and a very close friend,” says Sirbaz about Ali Sadpara. “I consider him as one of the finest mountaineers in Pakistan. We would frequently have meals together at the [Everest/Lhotse] basecamp. We’ve done Nanga Parbat, K2 and now Lhotse together.”

What’s in store for Sirbaz now? “I plan to attempt climbing Broad Peak (8,047m) and Gasherbrum 2 (8,035m) in June… as soon as my foot recovers!” he laughs. How long has his doctor said that would take? “The doctor said I should wait one and a half months but when June-July come in Pakistan [its peak trekking and climbing season in the country], who wants to stay at home?!”

Published in Dawn, EOS, June 2nd, 2019

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia