Pakistan is among the 21 countries which were “not free” in terms of freedom and access to Internet use

Herald Report

Islamabad: Internet freedom in Pakistan has further shrunk due to blocking of websites, shutting down of networks and increasing disinformation during the last one year, finds a report.

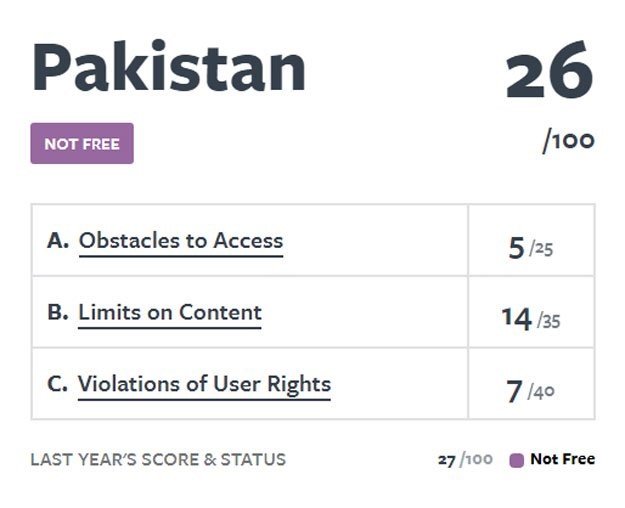

According to a report “Freedom of the Net 2019” which assessed 65 countries, global internet freedom declined for the ninth consecutive year as “populist leaders and their armies of online supporters seek to distort politics at home”. Of the countries surveyed, only 15 were “free”, 29 “partly free”. Pakistan is among the 21 countries which were “not free” in terms of freedom and access to Internet use. Each country is ranked on a scale with 100 representing the freest conditions and 0 the least free. A combined score of 100-70 = free, 69-40 = partly free, and 39-0 = not free. Pakistan ranks 26 out of 100, a drop from last year’s score of 27, for its score on Obstacles to Access because of poor infrastructure, Limits on Content and Violation of User Rights (intimidation, blackmail, and at times violence, in response to online activity).

The report found that election interference marred the online landscape in 26 of the 30 countries held over the past year, focusing on developments that occurred between June 2018 and May 2019. It also mentions increasing monitoring of dissenting voices on social media as well as threats and physical attacks on journalists and rights activists.

“The Internet in Pakistan is increasingly being used as an alternative medium to share information by dissenting political voices. As censorship in mainstream media grows, the government is looking for ways to control this alternative information resource,” says Sadaf Khan, Director Programs and Co-Founder of Media Matters for Democracy, a non-profit organisation working on media development and digital rights in Pakistan.

The decrease in Pakistan’s Internet freedom ranking is not a surprise. “I think we will see further regression in the way the State is looking at the Internet and trying to control it,” she suggests.

Ms Khan says the report is a wake-up call for civil society and digital rights activists to work together to push for a “more progressively regulated Internet in Pakistan.”

Limits on content

Pakistan ranked 14 out of 35 in terms of limitations of online content, according to the report. The report cited the blocking of AWP and Voice of America’s Urdu and Pashto websites as examples of content getting blocked without any reason. Social media platforms — Twitter and Facebook — also complied with the government to remove contents that were allegedly blasphemous, defamatory or containing hate speech. The report also noted PTA’s failure to issue notices before blocking websites or content. The report highlights network shutdowns ahead of the 2018 elections, blocking of website of Awami Workers Party (AWP) which was later opened by the ‘authorities’ on the direction of the Islamabad High Court in September 2019.

During the 2018 election campaigning, the AWP’s official website was blocked by the PTA in the lead-up to the 2018 general elections, was restored after the party lodged complaints with the Election Commission of Pakistan and the Islamabad High Court (IHC) against the unconstitutional move by the authorities. The IHC gave its landmark verdict on the petition on Sept 19, 2019, which has now been included in the Global Freedom of Expression database at Columbia University, which cites landmark cases related to the freedom of expression from around the world.

In a situation when the space for dissenting voices and freedom of expression is shrinking and “the definition of freedom”, according to Dawn‘s columnist Rafiya Zakarya, “is being questioned from loudspeakers and megaphones, one act of courage by the IHC is being lauded.

“The government’s position — strident as it has been — remained the same. Counsel for PTA argued that Section 37 of Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act gave them the blanket authority to block any website of any party or organisation at any time, based on their independent (and unclear) estimation of national security needs, writes Ms Zakariya.

One of the lawyers representing the AWP maintained that basic due process rights guaranteed in the Constitution are required to be read into any statute that is passed by the legislature. When pressed on the issue of the lack of specific rules for blocking websites, the PTA lawyers admitted that there were no such stated rules.

IHC Chief Justice Ather Minallah observed that PTA is not empowered to pass an order or take action under Section 37 of the Act of 2016 in derogation of the mandatory requirements of due process.

He added that the PTA had the responsibility to set out rules regarding the blocking of particular websites and to provide due notification of these rules. The CJ held that the rules should already have been provided given that the act itself was passed some time ago. The court gave 90 days deadline for the provision of the rules after the issuance of the decision in the case.

However, the court did not give any verdict on spoken words or speeches made by certain radical religious groups as mentioned by Ms Zakarya: “the court did not make a ruling on the fact that there were no restrictions placed on spoken speech while websites and online material were being blocked. This matter is relevant in the context of freedom of expression. The fact that the government and PTA consider themselves as having broad powers to assault the rights of political and other organisations that rely on their online presence while leaving untouched those that rely on other forms of organisation is notable…It should be noted that restrictions implemented with great vigour on one and not another can be considered indicative of the government’s own motives.”

“Certain kinds of political movements are welcome in Pakistan, despite all the venom and divisiveness they inspire. It does not matter how much their actions disrupt the lives of ordinary people, the costs they impose on the taxpayer-funded infrastructure. Nor are the security costs and threats imposed by such gatherings considered worthy of the same blanket and unexplained blockages that are the lot of other groups,” Ms Zakarya noted.

The framework of laws and freedoms and then the regimen of who they are enforced against all determine who is permitted to be vocal and who is permitted to be visible. Indeed, there are those who are trying to tread the trail of the good and the right; Justice Minallah is one of them. At a moment where exhaustion has set in and depredations issue fast and furious from the mouths of so many, such individuals are to be lauded. Perhaps others, faced with similarly momentous decisions in the future, will do the same — and focus on the question of how those that rouse thousands with angry words are as deserving of scrutiny as those who put up their official website on the internet, she argues.

Among other practices, it is such ad hoc content restrictions that have resulted in Pakistan being among countries “where governments are increasingly using social media to manipulate elections and monitor their citizens”, Human Rights Commission of Pakistan said.

While disinformation was the most commonly used tactic, authorities in countries blocked websites or cut off access to the internet “in a desperate bid to cling to power”, the report says.

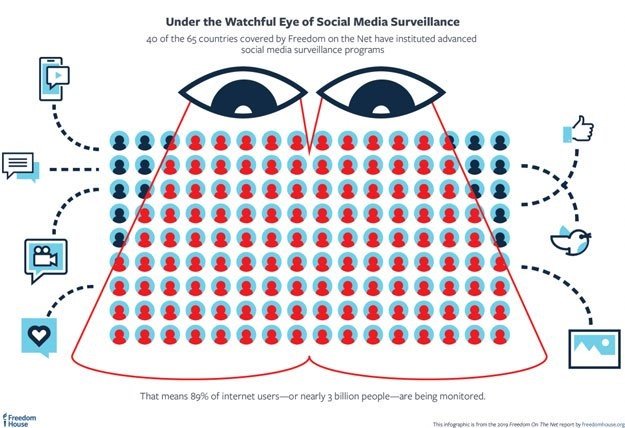

Governments were indiscriminately monitoring citizens’ online behaviour “to identify perceived threats – and in some cases to silence opposition.” The report found evidence of advanced social media surveillance programmes in at least 40 of the 65 countries analysed.

Obstacles to Access

The report has scored Pakistan 5 out of 25 in terms of access to the Internet. Authorities in Pakistan, a country with 67m broadband connections, increased blocking of political, social, and cultural websites. Over 800,000 such websites remain blocked. The report also highlighted the digital divide and the monitoring of digital activities of women within their homes. Many people in rural and under-developed parts of the country still do not have access to the Internet.

Between July to December 2018, the number of content restrictions by Facebook doubled from 2,203 (January to June 2018) to 4,165 items.

During the same period, authorities reported 2,349 profiles to Twitter with the request to remove 193 contents from the platform.

The government also sent 214 requests to Google to remove 3,125 contents between July and December 2018, up from 196 the previous six months.

“The PTA…routinely restricts content in a non-transparent and arbitrary fashion. While PECA legally mandates that the PTA issue notices when restricting content, in practice the agency rarely does,” the report said. “This lack of written notices impedes the ability of those impacted to appeal the orders or undertake a judicial review.”

Internet bots supporting various political parties surfaced ahead of polls. According to a study it cited, 52 percent of accounts using #PMLN, associated with the country’s main opposition party, were bots, while 46 percent using #PTI, the party that is currently in power, were bots.

In April 2019, Facebook removed a number of pages, groups, and accounts that had posted content on or operated pro-military pages.

The group cited a report from the Oxford Internet Institute, released in September 2019, which identified Pakistan as having “coordinated cyber troop teams with full-time staff members employed to manipulate the information space”.

The report identified that such teams work to support preferred messaging of their clients, attack the opposition, and suppress critical content. “Pakistan is alleged to have fake accounts run by both bots and human accounts, and most often manipulates content on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter,” the report said.

Authorities shut down mobile and internet service during protests and in the lead-up to the polls. “Mobile internet services were notably suspended in parts of Balochistan, and in all of FATA during both the election period and the lead-up,” the study said, adding that “mobile and internet services were shut down in parts of Lahore ahead of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif’s return to Pakistan from London before the general elections, impeding rallies of supporters welcoming him back.”

The government increased social media monitoring, announcing a new system to target extremism, hate speech, and anti-national content. “In a troubling development during the coverage period, the Federal Investigation Agency announced in February 2019 that it would implement a social media monitoring system to target extremism, hate speech, and anti-national content online,” the report said. “The system would allow authorities to take action against users under the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016.”

Violation of user rights

Pakistan ranked 7 out of 40 in terms of violation of Internet user’s rights, the report says. Journalists and activists have continued to face intimidation and threats due to their online expression. Journalists and activists were abducted and physically attacked, the report found citing an investigation into “targeted social media campaign” against Saudi Arabia when Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman was visiting Pakistan earlier this year. The report also found online violence directed at women, such as in the aftermath of the Aurat March in 2019, which restricted their online activities.

Commenting on the report, Usama Khilji, a digital rights activist, said, “In the last year we have seen the pressures on freedom of expression and privacy increase from state-led efforts to trample on speech and increase surveillance, especially with the setting up of the web monitoring system, and blocking of political content on the internet,” he told The Express Tribune.

However, he added, there have been some welcome developments, such as an effort on part of parliamentary committees to amend the draconian PECA 2016, and some court decisions that call on the government to not block political content on the internet and follow stipulated legal processes in regulating online content.

“It now all depends on the intent of the state to protect fundamental constitutional rights guaranteed under Article 14 as the right to privacy, under Article 19 Right to Freedom of Speech and Press, and under Article 19-A Right to Information,” the director at BoloBhi said, when asked if Pakistan’s standing could improve. “However, that does not seem likely, as those in control currently benefit from silencing democratic forces.”

The frequent disruption of telecommunication services during protests, holidays, elections and religious gatherings also limits access. The report also noted irregular changes in the telecom policies that make it harder for telecom companies to operate and the concerns related to transparency and independence of the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) as a regulatory body for the Internet.

Disinformation was rampant during the reporting period, aided by “troll armies” who spread false information, such as journalists, under coordinated hashtag campaigns on Twitter. Government surveillance caused journalists to self-censor, therefore limiting content.