Artists, historians, and writers are marking Punjab’s secular epic, 250 years after it was penned by Waris Shah.

The legend of Heer-Ranjha is believed to have played out in real life on the banks of the river Chenab, way back in the second half of the 15th century. This was the site that many poets chose to tell the tale of the lovers, writes Nirupama Dutt in the scroll.ind an online news portal.

For instance, Pakistani scholar Muhammad Sheeraz places it thus: “For centuries, the Chenab River has been flowing through the soils of the Punjab, the land of five rivers, and its fast and furious waves have told tales of love and romance. Heer-Ranjha is one of the tales told in unison by the waters of the Chenab.”

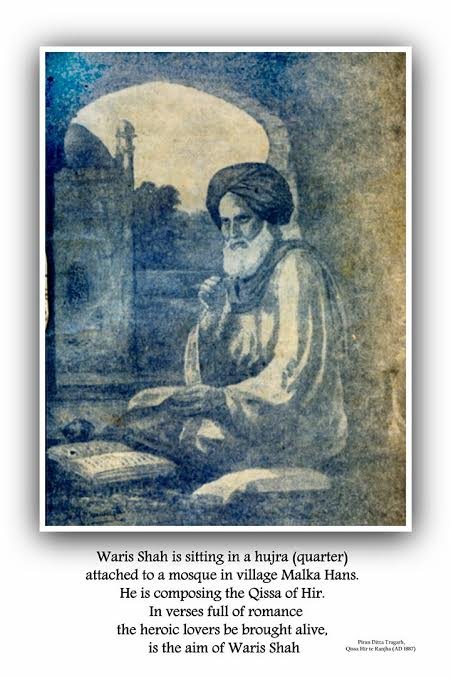

It was the rendition by Sufi poet Waris Shah, completed in 1766, that captured the imagination of the Punjabis. His Qissa is an all-time classic and a bestseller. Chandigarh-based historian Ishwar Gaur, who sources his writing of Punjab’s history from folklore, Sufi poetry and Gurbani, said about Waris’ text:

“It is a complete socio-cultural text of the turbulent 18th Century Punjab and truly secular in nature and it is time we acknowledged its value and not treated it as mere erotica.”

Lahore-based Punjabi writer Zubair Ahmad echoed Gaur’s sentiments, saying: “Waris was loved across borders, and is one of the most significant poets of Punjabi, who stood for unity and assertion of women’s identity. That is why famous modern poet Amrita Pritam called out to him in her immortal poem on the Partition, ‘Ajj akhan Waris Shah nu…’ (Waris Shah, I call out to you today).”

The text is quoted as part of spontaneous everyday conversations in Punjab, so it was not surprising that litterateurs chose to celebrate 250 years of Heer Waris, as the legend is popularly known. A call for celebrations was sent out through social media, on the cross-border literary group ‘Kitab Trinjan’.

London-based Punjabi poet Amarjit Chandan said on the Facebook page of Kitab Trinjan that he wished for a celebratory Indo-Pak literary event, at the mazaar of Waris in Malka Hans village, near Pakpattan in Pakistan, and postage stamps commemorating Heer-Ranjha in both countries.

Star-crossed neighbours

Of course, none of this happened. As the year progressed, India-Pakistan relations grew tense. The establishment chose to stay away from celebrating this legend of love and revolt, but poets, writers, and historians chose to mark the year regardless, with literary and art events in the two Punjabs, separated by the barbed wire of the Line of Control. They held readings, discussions at the SOAS University, London, with scholars from India and Pakistan. Jasbir Jassi and Madan Gopal Singh sang Heer in Delhi.

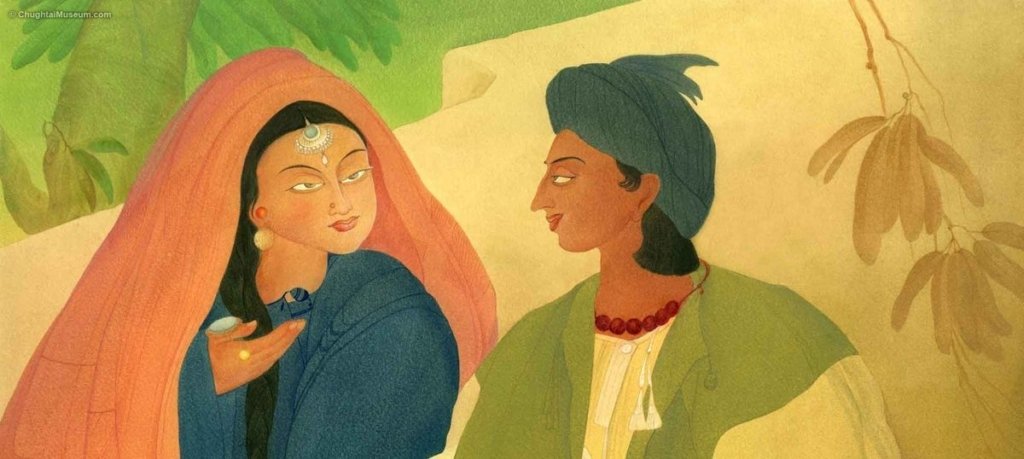

It has been refreshing to assess the medieval heroine who dared to transcend social bounds for her lover Ranjha, whose first name was Dheedo. Another prominent Sufi poet of the 18th century, Bulleh Shah, described the intensity of her passion, in the first person, as Sufi poets are known to do when speaking of love:

Ranjha Ranjha kardi hun main aape Ranjha hoyi

Sakhiyo ni mainu Dheedo Ranjha, Heer na akho koyi

(Chanting the name of Ranjha I myself am Ranjha now

My friends call me Dheedo Ranjha not Heer anymore)

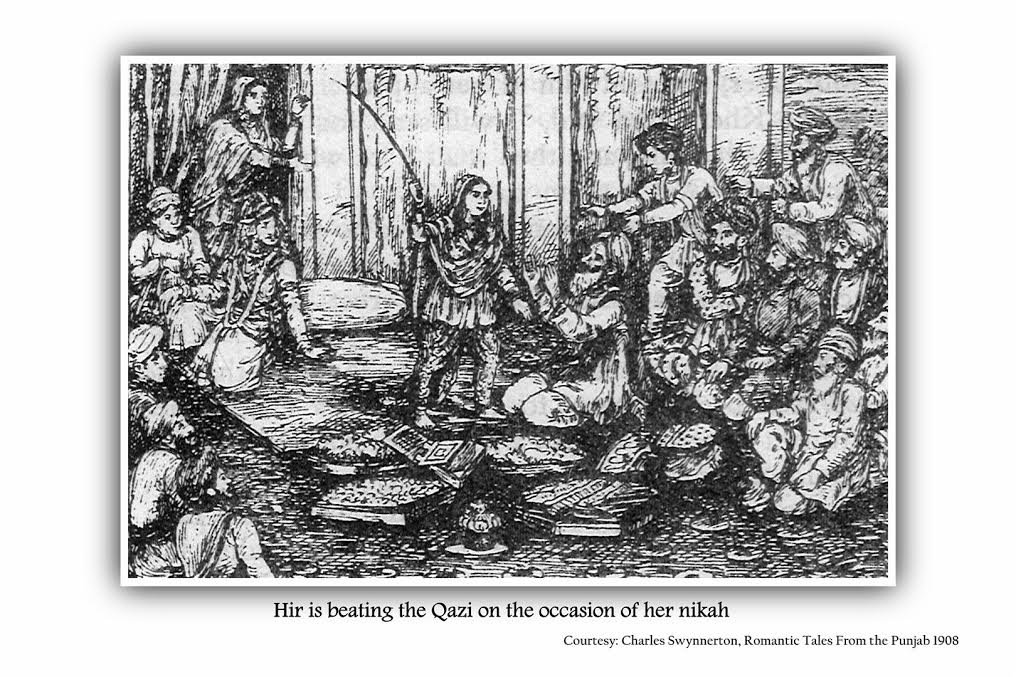

Gaur, who had authored a book in 2008, called Society, Religion and Patriarchy: Exploring Medieval Punjab through Hir Waris, chose this year’s anniversary to mount an exhibition at the Panjab University Museum, a rare collection of the depictions of Heer-Ranjha in popular art. He collected visuals from the copies of Qissa sold at fairs and festivals over a quarter of a century, as also from magazines and journals.

Laying emphasis on the spirit of Heer, Gaur said, “Not only does Heer fall in love, but she fights for her right to love and marriage as per her wish.”

The exhibition includes three graphics in which Heer, the daughter of the soil, is shown beating Ranjha when she finds him resting in her boat by the Chenab, with her villainous uncle Kaidon and the Qazi, the religious head.

“The text of Heer-Waris confirms only her beating Kaidon, the rest are folk perceptions,” Gaur said. “She does confront Ranjha when she sees him the first time, asleep in her boat, until their eyes meet and they fall in love. She argues with the Qazi forcefully, and the folk view is that she has beaten him for his bigotry. In fact these works celebrate the spirit of Heer who has ruled the hearts for so many centuries.”

Worthy to note, as one salutes the spirit of the medieval maiden and the poet who penned her 250 years ago, that Heer’s name was once never given to a girl child, lest she develop the independence and fearlessness of her namesake. However, over the past decade or two, some young parents have named their daughters Heer even though their number is few. May the tribe of Heers multiply.–Courtesy: scroll.ind

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia