Abhrajyoti Chakraborty on a giant of the Bengali renaissance

When Rabindranath Tagore died in 1941, crowds gathered outside his ancestral mansion in Calcutta hoping to catch a last glimpse. As soon as the body was brought out of the house, everyone charged toward it at once. Hairs were plucked from his beard, wreaths tossed from buildings on the funeral route. In Satyajit Ray’s documentary of the poet, the corpse is seen floating above a sea of human heads. The roads were so crammed that Tagore’s son Rathindranath could not reach the cremation ghat near the Ganges to light his father’s pyre. The ghat had been cordoned off for a week in preparation for the funeral, but once the fire was lit, people broke in, looking for bones and other remains. The body wasn’t yet burnt, and mourners were scavenging through the ashes, screaming and cursing.

Mrinal Sen was in the crowd outside the funeral. He was new to the city, a student at the Scottish Church College, which had canceled classes after reports of Tagore’s demise. Sen had reached the ghat beforehand to get a good view, but the policemen near the entrance made him stand at a distance. He was waiting for the procession to arrive, he wrote later, when he spotted a young man dressed in white on the other side of the police cordon. “He was standing with a child in his arms, his own, so I thought, wrapped in a milk-white towel. Most probably, he came to cremate the child and was caught in a cruel situation. Why did he not go to another crematorium?”

All of a sudden, there was a surge of crowd. From different directions. As if, to attack the crematorium. […] All the protective measures failed, the cordon was broken totally. Everything was out of control. […] A stampede? Any casualty? Anyone’s guess! And the child? The child was lost, drowned in the crowd. So was the man.

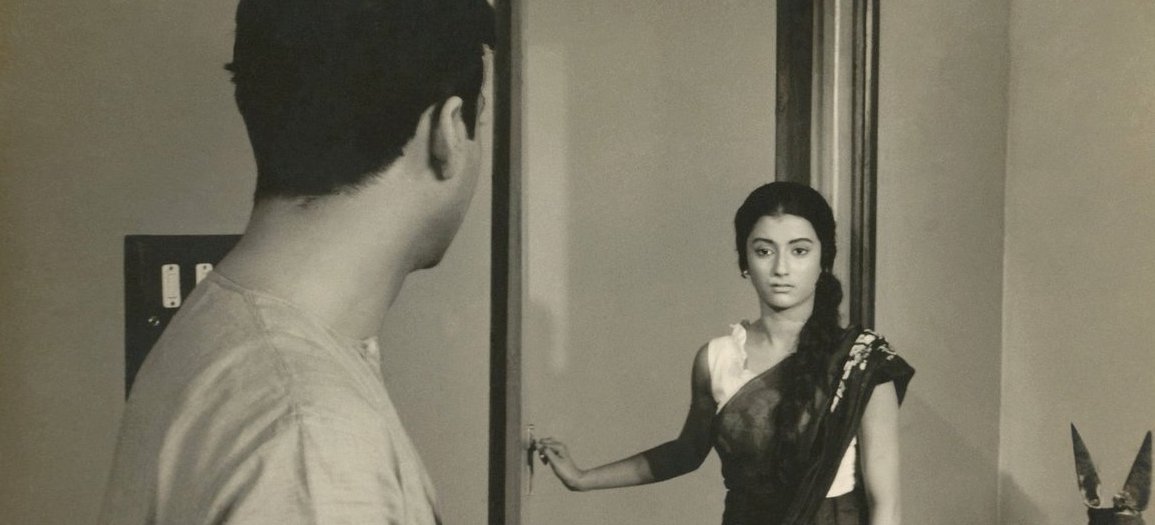

Twenty years later, when Sen made a film set in the period of the devastating 1943 famine in Bengal, he called it Baishey Sravan—the date in the Bengali calendar that marks Tagore’s death. In the film it is the day when a middle-aged salesman gets married to a younger girl in a village. His forebears may have lorded over the village as wealthy landowners, but now the man makes a living selling dyes on trains. Early in the marriage he tells his wife that he is only reaping what his ancestors sowed: “Who knows how many perished struggling to pay their dues? Or who had to suffer in what way to indulge my family’s whims?”

By the time of the famine, the man is unable to walk, or work; he can no longer put his situation into perspective. He finishes off his meals without caring if there is enough for his wife to eat. Each day she suffers just to keep him going. His circumstances are not to blame, his wife tells a friend: “It is him—he has changed, he has become selfish.”

By the time of the famine, the man is unable to walk, or work; he can no longer put his situation into perspective. He finishes off his meals without caring if there is enough for his wife to eat. Each day she suffers just to keep him going. His circumstances are not to blame, his wife tells a friend: “It is him—he has changed, he has become selfish.”

The tragedy of the famine—implied in the film through a brief scene of villagers queuing up to buy rice—is overshadowed by the couple’s relationship, the speed with which husband and wife end up being pitted against each other in order to survive. It is akin to the way in which, for Sen, Tagore’s passing paled beside the death of a child in the crowd.

*

When Sen died a year ago, the question of what would happen to his films was glossed over in the obituaries. His passing, like Tagore’s, was drowned by a ceremony of passion and indifference. The crowd chose what to remember and what to forget. Elaborate noises were made about the “end of an era,” and that in death Sen had been reunited with other Bengali giants like Ray and Tagore.

But Ray’s and Tagore’s legacies are far from certain in a country that could not salvage the original negatives of Ray’s renowned Apu trilogy before they vanished in a fire back in 1993, or recover Tagore’s Nobel Prize medallion after it was stolen in 2004. Sen, too, had to opt out of a 2009 retrospective in Cannes because the prints of his Calcutta trilogy were in terrible shape. His early films have already disappeared. In the months since his death, the fear has been that his work will be preserved only in memories.

Tagore had foreseen this indifference, this overwhelming “suspicion of man for man,” something he saw emerging from the same spirit of conflict and conquest that he detected in both Western imperialism and the nationalist movement in India. Yet his position was complicated by the prodigious wealth of the Tagore family over generations, wealth that no doubt helped him step out of the apparatus of colonial power and resistance and forge his own distinct way of looking at the world.

The Tagores had been at the center of the Bengal Renaissance—the astonishing tide of social and intellectual activity that accompanied the formation of a secular modern bourgeoisie in the early 19th century, and turned Calcutta into a booming literary city. But these ideas and texts had failed to trickle down beyond the educated middle class. The majority of Bengal—and India—had no way out of the imperial trap. Their advantage over the British was, after all, contingent on numbers: the strength of their crowds.

The Tagores had been at the center of the Bengal Renaissance—the astonishing tide of social and intellectual activity that accompanied the formation of a secular modern bourgeoisie in the early 19th century, and turned Calcutta into a booming literary city. But these ideas and texts had failed to trickle down beyond the educated middle class. The majority of Bengal—and India—had no way out of the imperial trap. Their advantage over the British was, after all, contingent on numbers: the strength of their crowds.

Sen grew up trapped between these limited choices. Born in 1923 in Faridpur, a town now in Bangladesh, his father was a lawyer at the district court whose sympathies were with the freedom movement. Sen’s most vivid memories of his childhood were of attending rallies and protests, getting involved once or twice in the ensuing violence, and being detained in a police station while still in primary school. It was only in Calcutta where, as he said later, he learned to read everything he could—and through reading began to develop a sense of himself as slightly apart.

The break was never clean, however. In the city Sen was influenced by the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was set up in the wake of World War II and the Bengal famine. The artists’ guild had ties with the Communist Party of India, and many of its members went underground after independence. Sen, though a “private Marxist,” did a lot of organizational work—smuggling posters, writing plays, shielding fugitives from time to time. He was forever flitting between objectivity and commitment.

India became independent when Sen was in his mid-twenties, but the country kept much of its colonial machinery intact. In Bengal, the horrors of the famine were compounded by the creation of East Pakistan—later Bangladesh—followed by carnage on both sides of the border. The loss of life and property threatened never to end. Trains would arrive in Calcutta teeming with refugees; while the dead would be unloaded, those alive would disembark on the platforms and remain there, whole families camping with their belongings beside the tracks.

Despite these crises, the city’s cultural life flourished. Apart from the IPTA, there was the Calcutta Film Society, set up by Ray with a friend, which organized screenings of international films, invited visiting directors like Jean Renoir and John Huston to speak, and published bulletins of film interviews and criticism well before Cahiers du Cinema was founded in Paris. A cohort began to emerge, interested in the imaginative possibilities of filmmaking and disdainful of the exaggerations and sloppiness that prevailed in most Indian films.

Ray’s superior sensibilities were evident in his circle, and he was the one most expected to succeed. Ray had learnt well from Tagore. He had immersed himself in honing his craft through the war years, cultivating a focused detachment. In his spare moments, he developed alternative storylines for films under production, designed book jackets, taught himself how to read and write Western musical scores. When his employers sent him to London for further training, he watched 99 films in the space of six months.

After watching Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, he knew that he wanted to shoot outdoors on a low budget with a nonprofessional cast. By the time Ray made his debut in 1955, he was, in many ways, assured of his antecedents. The maturity of the Apu trilogy—tracking a Bengali boy’s journey from the village to the city—was not an aberration: the spirit of the Bengal Renaissance had found a new form.

*

Sen’s apprenticeship was never so ordained. After Partition, his parents sold their house in Faridpur and moved in with him in the city.

For a while, Sen worked for a pharmaceutical company, traveling through central India as a marketing representative. He came to cinema through reading—Rudolf Arnheim’s Film, followed by Vladimir Nilsen’s Cinema as a Graphic Art, which in turn led him to Eisenstein and Pudovkin. He translated a novel by the Czech writer Karel Čapek, then wrote a book on Chaplin. In 1948, Sen wrote a script based on a peasant uprising that had broken out in a town 50 miles away from Calcutta. He had just figured out the logistics of shooting on location when he heard that the police were planning to raid his apartment. He went home at once and burnt the script.

Baishey Sravan, released in 1960 and shown outside India as The Wedding Day, was Sen’s attempt to reckon not just with the excesses of the past, but also with the possibilities Ray had opened up for Indian filmmakers with the achievement of Pather Panchali, the first installment of the Apu trilogy. Both films are set in rural Bengal; both were acclaimed in film festivals abroad before being feted at home—but that is where their similarities end. Ray allows his characters to daydream and discover things on their own: little Apu and his sister can always run away from home and disappear into the golden landscape.

Even at their happiest, the couple in Baishey Sravan cannot escape into each other’s arms. Because of their age difference—and inexperience—Sen suggests that sex between them is an encumbrance. They look up to see planes flying overhead without dropping any food supplies. Their surroundings can only remind them of the desperate lives they lead. No poem will reflect their true predicament, no conceivable change in their situation repair what they have lost in their relationship. History will record the number of people dead in the famine, not the end of the couple’s marriage.

Bhuvan Shome has the air of having emerged from a provisional script. Much of the action is wordless, the conversations no more than plausible.

Akash Kusum (Up in the Clouds), made five years after Baishey Sravan, is about another doomed couple. Ajoy pretends to be a successful businessman in order to impress Monika and her parents. He borrows a well-to-do friend’s clothes, tells Monika that this friend’s apartment is his own. Hoping to get rich quickly, he ends up investing in a risky venture for better profits. The inevitable happens: Ajoy’s new business sinks without a splash, the girl’s father finds out his lies before he can come clean. The father blurts out everything he is thinking—“Fraud! Cheat! Impostor!”—in a sentimental final scene.

From Akash Kusum onward, one notices a preponderance of freezes and stills in Sen’s work. He had picked up the idea from François Truffaut, as countless filmmakers had after watching The 400 Blows. The freeze fit perfectly with Sen’s wish to inhabit a moment and be self-consciously outside of it. Ajoy’s motivations, however familiar to us, seldom feel hackneyed in the film. His gestures seem in keeping with his confidence. Sen is able to convey the naiveté behind Ajoy’s ambitions with the frequent stills.

Without any memory of the frozen frames, a viewer might think of the last shot—Monika waves at Ajoy from her window, and he reluctantly waves back—as a director too neatly wrapping things up, but the prior pauses and interruptions undercut any certainty about that moment. Instead, one realizes what happened between the couple was not so much a romance as a reckoning.

Ray found Sen’s films to be “naïve” and didactic. He famously dismissed Sen’s next major release, Bhuvan Shome, in seven words—“Big Bad Bureaucrat Reformed by Rustic Belle.” But this judgment is itself naïve. What sustains interest in the film is not the story, but the character of Mr. Shome, the big bad bureaucrat. Mr. Shome may be old, yet his inner life is that of an imp. His reputation of being stern at work is repeatedly undermined by his antics in the course of a hunting trip, and the girl he meets in a village recognizes a fellow spirit.

She first sees him hiding from a buffalo on top of a tree. He sees her coolly ride away on that buffalo, laughing at him for being so afraid. Their affinity for each other is hard to describe: words like “reform” or “romance” don’t quite capture it. One moment they are tramp and child in Chaplin’s The Kid, the next moment king and queen in the ruins of a palace. Back in his office, Mr. Shome is still a bureaucrat—not reformed but, somehow, revived.

Bhuvan Shome has the air of having emerged from a provisional script. Much of the action is wordless, the conversations no more than plausible. Sen appears to cherish the film’s clumsier aspects. When Mr. Shome is introduced as a Bengali, portraits of Ray and Tagore appear on the screen followed by a shot of the protagonist doing squats to prepare for the hunting trip. Later, while he is being chased by a buffalo, for a split second we are shown Mr. Shome back in his office poring over a book. The implication is clear: Mr. Shome can study all he wants; sophistication won’t save him. Courtesy: The Point

Abhrajyoti Chakraborty is a writer living in New Delhi. He has written for the New Yorker, the Guardian, the New Republic and the Times Literary Supplement. His essay on Mrinal Sen appeared in issue 21 of The Point.

Abhrajyoti Chakraborty is a writer living in New Delhi. He has written for the New Yorker, the Guardian, the New Republic and the Times Literary Supplement. His essay on Mrinal Sen appeared in issue 21 of The Point.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia