By Anita Bakhtiar

If you want an honest and surprising look into what the ‘Me Too’ Movement constitutes without bookish definitions, watch the movie ‘Bombshell’. A movement primarily catapulted by Hollywood and mainstream American media, this movie follows the results of a sexual harassment lawsuit by a Fox anchor who was fired from her job by a very powerful man. The use of surprising to describe this movie is accurate because it nimbly explains gray areas related to the movement. Why do powerful women speak up much later? Why do most women refuse to speak up? How is ambition tempered by caution in an industry that is predominantly male in its corridors of power?

The ‘Me Too’ movement seemed eons away from us when it began. Big names with big money were accused of sexual harassment, exploitation, and downright assault. The accusers were big-time actresses, unknown crew members, rising starlets-powerful men, and women, it seems enjoyed the power associated with coercing attractive individuals for intimacy.

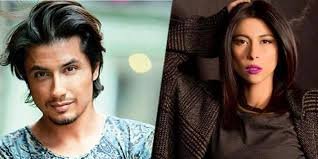

Then came Meesha Shafi, with her explosive reveal — or shall we say accusation — against costar Ali Zafar. The backlash that Shafi faced as a consequence of this was so negative that it remains unparalleled in Pakistan. She has been accused of lying solely because she is a strong, unapologetic woman. Her pictures have surfaced on media, from various elements, pointing out her clothes and her familiarity with the accused. We pretended that harassment takes place between strangers, that women who are covered from head to toe do not face it, that confident women are unlikely to be targets of such behavior.

Without going into the resulting dynamics of Shafi’s accusation, I would like to remind us that harassment-particularly in Pakistan-is widespread across public spaces, offices, and institutes. It is the result of condescending attitudes as men (and many women) believe that women are incapable of working ethically or professionally and thus look for favors; or men and women believe that independent women are promiscuous-or that women that smile out of politeness, or respond to small talk are welcoming their sexual overtures. Newsflash: this is not true. Also, while the Law against Harassment in the workplace is in effect and the Federal Ombudsman is quite active in its pursuit of cases, women think many times before bringing their complaint public.

An inherent message of the ‘Me Too’ movement is that of consent, or the right to choose and to say no. While these are messages that do not contradict our religious scripture in any way, our culture has always encouraged a rather desperate kind of sexual expression. Our novels speak of one-sided, tragic love stories, our films and dramas show haughty women being won over by the persistence of their well-meaning but dangerously obsessive admirers. Women are either hesitant to engage-in which case the man must masterfully convince them of their own heart. Or, they are head over heels in love, risking reputation and family for a man.

Much like the nation’s reception to the ‘Me Too’ movement, our local media content is also faced by the halo and horns effect. Some individuals or groups — often those acceptable to popular movements or platforms — enjoy the halo effect wherein their messages or content receives vastly positive feedback. Then there are others, singled out for their personal problematic views or affiliations that suffer from the horns effect, criticized for even trying to express their opinion on society’s dire realties. This was witnessed recently for Mere Paas Tum Ho, the recently concluded widely successful TV drama penned by controversial playwright Khalilur Rehman Qamar. The drama’s success was nearly overshadowed by the bewildering response to its’ approach towards a difficult topic: the cheating wife. The writer’s personal deeply unsettling views on women are unfortunate and may have had an impact on the plot and script. He is however, I am certain, one of many others just given more airtime. One has simply to browse through our dramas, whatever the channel, to decipher this.

The drama proved to be vastly entertaining for an entirely unexpected reason. Penned in the writer’s rather unusual dramatic expression, the plot revolved around a married woman with a young son cheating on her doting yet poor husband with a charming and rich businessman. Now the average husband in Pakistan has the liberty of beating his wife says the Council of Islamic Ideology (without breaking any bones, of course), particularly for infidelity. That’s just our reality: the average husband when cheated on is seen as weak-the cheated wife is simply unfortunate. Mahwish, in reality, would have heard or experienced far worse than depicted in the drama’s (in)famous scene. where her husband tells her lover that she is hardly worth two pence, much less the monetary amount he was offered for her.

Ironically, the drama illustrated that infidelity is equally and unanimously damaging whether done by the man or the woman. Very rarely do we see a woman genuinely won over by a man’s maturity, his gentleness, his goodness. Such men meet rather unfortunate endings — such as Humayun Saeed in ‘Mere Paas Tum Ho’ — for such a man can never keep a woman engaged. It is the rogue, the playboy –the Harvey Weinstein or Shahwar Ahmed let’s say — who gets the girl. This is dangerous business because we have filled out young women’s’ heads with the idea that decent men who seek your consent or wait for your approval are somewhat pathetic, while the alpha male singing songs to inform your neighborhood that he is in love with you deserves a medal: you. It is time to move past the assertive man winning over the woman of his dreams through actions that would humiliate her in our reality. Especially here in Pakistan, where such love stories have also resulted in acid attacks and murders because the girl said ‘no’.

Anita Bakhtiar is an Islamabad-based writer. She has nearly fifteen years of experience in strategic communication, capacity building and linkages development. An avid reader, cultural enthusiast, she advocates social causes.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia