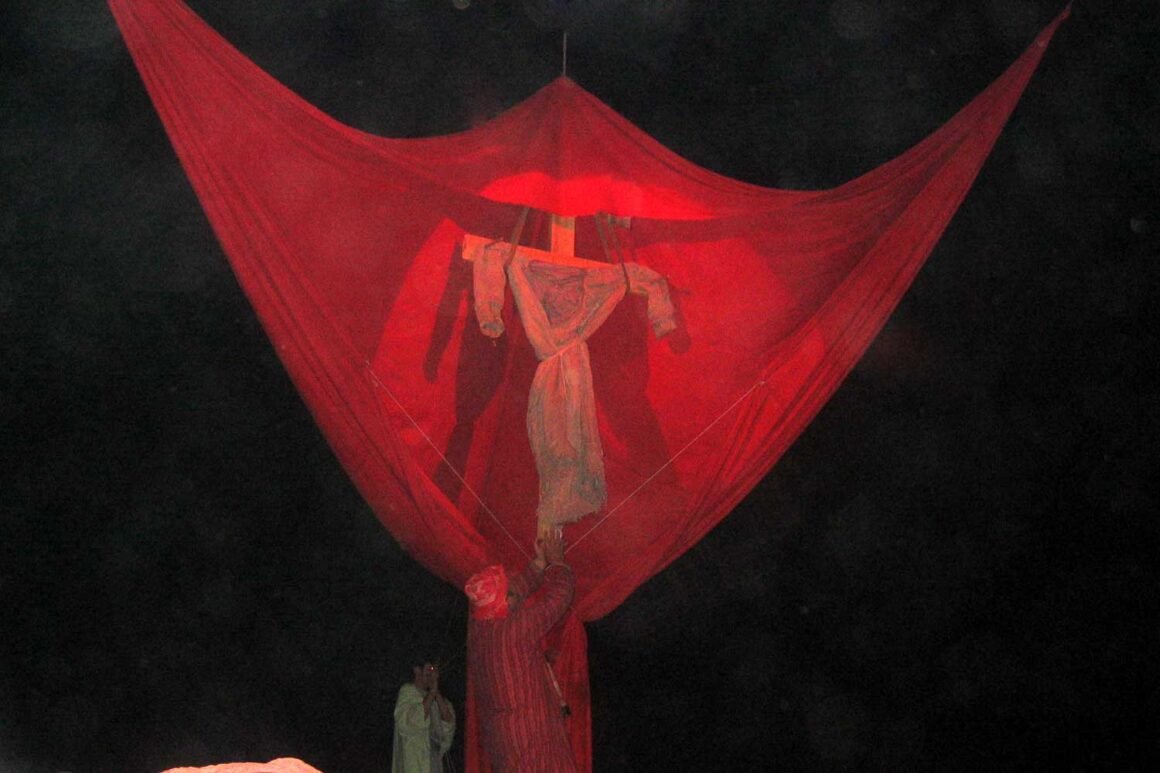

Five-wives-of-Khodja-Nasreddin_-dir.-Olim-Salimov-Mayakovskiy-theater-photo-Ulugova

Five-wives-of-Khodja-Nasreddin_-dir.-Olim-Salimov-Mayakovskiy-theater-photo-Ulugova

Lolisanam Ulugova traces the roots, evolution and contemporary theatre in Tajikistan which goes back to ancient centuries. In her essay in the online magazine Voices on Central Asia, she discusses in detail how do theaters in Tajikistan thrive and act at times when politics in the arts is too dangerous?

My recent visit to Tashkent (the capital of Uzbekistan) was marked by the exploration of several theaters. I saw two plays: The first, Zavtra (Tomorrow), was staged by Artyom Kim, based on the script of Nikita Makarenko, and revolved around the insecurities associated with urban planning; the second was the production of Sayfiddin Meliev’s Tillo Tabasumlar (Golden Smiles), which was based on Abdullo Kodiri’s Turon Theater and focused on high taxes. At the same time, theaters in Dushanbe (the capital of Tajikistan) showed productions of Shakespeare: Hamlet (staged by Bakhodur Miralibekov in the Mayakovsky Theater), and Macbeth (staged by Firdavs Kosimov in the Ahorun Theater), each depicting the fate of royal power. An interesting detail about Tajikistan is that both productions were made in a presidential election year, and the plot of both performances speaks of a power struggle in which wrestling for the throne is a cross-cutting theme. How do theaters in Tajikistan thrive and act at times when politics in the arts is too dangerous?

How did it begin?

In his book, The History of the Tajik Soviet Theater (Donish, Dushanbe, 1967) (thanks to Katie Freeze for the copy), Nizom Khabibbullaevich Nurjanov (1923-2017) asserts that “the Tajik theater in its development had inherited the centuries-old traditions of Tajik national art that go back to ancient times. The earliest beginnings of the theatrical activities of Tajiks could be seen in the agricultural songs associated with customs and rituals and in spring festivals of flowers originating from ancient mysteries.”

Tajik professional dramaturgy originated in the bowels of the Lakhuti Drama Theater (1929). Discussing the early Tajik plays, Nurjanov described them as “a head-on solution to the conflict, a poster image of the individual phenomena of reality, an inept construction of the composition.” It was not until 1934 that the Lakhuti theater turned to western European drama when it staged the play Princess Turandot by Carlo Gozzi. This was one of the first national performances staged by Khomid Makhmudov (1900-1977). He was one of the first organizers of the Tajik theater and spent much energy on the selection of artists, musicians, and technical staff to attract young authors and educate actors.

The poem Shahnameh (Book of Kings) by Abulkasym Firdawsi is an icon of Tajik-Persian literature that glorified the braveness and courage of folk heroes with its humanism, sharp dramatic scenes, and powerful characters. It also was and remains a brand to reflect “Tajikness.” Shahnameh based on a play by the Armenian playwright M. Janan was staged for the first time by Tikhonovich (1903-1970)in December 1935 out of a desire for the theater to expand contacts with fraternal Soviet republics. Tikhonovich was considered as Tajikistan’s first eclectic theater director. Speaking about him, Nurjanov pointed out that Tikhonovich had suggested two primary methods of theater development in Tajikistan, such as (1) “Orientalizing” the plays of Russian and West European dramaturgy and (2) “Europeanizing” the works of national playwrights, as well as enhancing the entertainment value of theatrical productions. In principle, this happened much later on. The embodiment of courage and heroism answered ideological questions, since the theater remained one of the essential institutes for the education of a “new human.”

Great Tajik theatrical directors

“Dajjal Antichrist” by Farrukh Kasymov, Ahorun Theater, archival photo by Janjalov

“Dajjal Antichrist” by Farrukh Kasymov, Ahorun Theater, archival photo by Janjalov

Farrukh Kasymov

Farrukh Kasymov (1948-2010) was the founder of the Sufi-poetry theater. In 2004, Farrukh Kasymov was awarded the Prince Klaus Prize (the Netherlands) for his contribution to the development of Tajik art. Farrukh Kasymov establisрed the Ahorun (City of Gods) Theater in Tajikistan. His wife, actress Sabokhat Kasymova, is now the artistic director and his youngest son, Firdavs Kasymov is one of the directors.

Last winter I met with Russian theater expert Anna Stepanova (1952) in Moscow to ask her about the artistry of Farrukh Kasymov. She highly praised Farrukh Kasymov’s play entitled Yusuf, which is based on the 12th Surah of the Koran, the Muslim analog of the biblical parable about Joseph the Beautiful and his brothers. The story of the prophet Yusuf was put to the music of ingenious verses by Rumi, Hafiz, Jami, and Sheikh Attor and showed some of the ritual forms that existed among the Sufi and the Shiites. Kasymov’s story ends with the brothers killing Yusuf—an eerie prophecy of the fratricidal civil war from 1992-1997 in Tajikistan.

In 1996, prior to the end of the civil war, the Ahorun Theater went on a production tour in Moscow. I saw poor-quality footage of a Moscow journalist’s interview with F. Kasymov. The journalist noticed the beauty of the Tajik artists in the theater, and he noted that it was discordant with what was happening on the street. The journalist asked how the things happening on the street differed from what was happening on the stage, where there were people beautiful everywhere. Ustod Kasymov confidently responded that there was “almost no difference between what was happening on the street and what was on the stage; the same beautiful people on the street also played the roles of murderers or victims, depending on the situation and circumstances.” In the same interview, Kasymov spoke about the significance and richness of the heritage of Persian-language literature, that it was unused enough, neglected, and that this wealth belonged to the people and should be with the people. “Our tour declares that we exist and we have not died,” Farrukh Kasymov tells the journalist, “any theatrical production should lead to catharsis, purification, and empathy because any theater is a temple, a place for prayers,” the master claimed.

Barzu Abdurazakov

Another major significant figure of Tajik theater is Barzu Abdurazakov (1959). Since 2010, he has been a dissident. Although authorities have reported that they are not against Abdurazakov’s work in the country, none have officially invited him to continue his professional activities (as he stated in one of his interviews). He fell out of favor after staging the play Madness: Year 93, based on Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade play. In 2009, a public activist Amal Khanum Gadjieva interviewed him on the opening night performance of Madness: Year 93.

The below quotation (shortened for clarity) is from this interview between Gadjieva and Abdurazakov:

“AG: The play Madness: Year 93 talks about the events of the 18th century Great French Revolution. It gave the world a set of ideas of social and human progress and democracy. The life path of Marat—the main character of the play—became an example for many generations of revolutionary fighters. But, despite the limitations of what is happening in the society, the performance is so relevant that we were all afraid of how the artistic council of the Ministry of Culture would react to it and even feared that it would not accept the play for our future repertoire. But the artistic council accepted it; moreover, they praised it. How can you explain this: the times of servility are already gone, and people are finally straightening their shoulders or…?

BA: I do not think that the times of servility are gone. The performance is invulnerable in content and quality, and people in the artistic council, headed by Ibrahim Usmon (state official), can evaluate it intellectually.

AG: Where did the idea come from?

BA: I didn’t want to get myself or my family into trouble. However, it is still my civic duty to say how I feel about the present and future of my country. We are not urging anyone to go to the barricades; Tajikistan has seen enough blood. We do not emphasize the political aspect, but we do emphasize the personal aspect. Either you are an active citizen of your country, or you are an eternal slave. And this is the main plot of the play.”

Theaters today

There are several major drama theaters in the country, including the Lakhuti State Theater, the V. Mayakovsky Russian Drama Theater, the Muhammedzhan Kasymov Ahorun theater, the M. Vohidov State Youth Theater, and other functioning theaters in various regions. The leading modern Tajik directors include Nozim Melikov, Sulton Usmonov, Bakhodur Miralibekov, Davlat Ubaidulloev, and Firdavs Kasymov.

Among the listed directors, I would like to focus on the work of Nozim Melikov (1966). His plays—A Night Away from the Homeland (script by Bozor Sobir), Ishtibokh (“Misunderstanding,” script by Albert Camus), Diravshi Kovayen (“Banner of Kova,” script by Firdawsi), When the Mountains Fell (script by Chingiz Aitmatov)—each reflect the current reality: migration and societal disorder.

Among the listed directors, I would like to focus on the work of Nozim Melikov (1966). His plays—A Night Away from the Homeland (script by Bozor Sobir), Ishtibokh (“Misunderstanding,” script by Albert Camus), Diravshi Kovayen (“Banner of Kova,” script by Firdawsi), When the Mountains Fell (script by Chingiz Aitmatov)—each reflect the current reality: migration and societal disorder.

Recent premieres

Two plays by Shakespeare have recently premiered in Dushanbe theaters: Hamlet, directed by Bakhodur Miralibekov (1950) in the V. Mayakovsky theater, and Macbeth, directed by Firdavs Kosimov (1987) in the Ahorun theater. The following paragraphs contain a brief description of each, as well as my own review of the productions.

In Hamlet, the main role is played by Khurshed Mustafoev (F. Kasymov’s follower, 1978), and the role of Ophelia is played by Munira Dadaeva (director of the Mayakovsky theater, 1970). In this production, Hamlet is portrayed as a misogynist, woman-hating, infantile young man that treats his mother and Ophelia without respect. Both women are shown as victims of their circumstances, passionately and sacrificially adoring their prince. Such focus seems an odd choice in a society where abuse towards women happens often. So it remains unclear to me what Miralibekov wanted to say by staging this classical play.

Another recent Shakespeare performance in Dushanbe was Macbeth, presented in the Ahorun Theater and directed by Firdavs Kasymov (1987). He took the plot of Macbeth but filled the meaning of the libretto with excerpts from Firdawsi’s Shahname. In my opinion, the eclecticism of the play was justified. The performance had good plasticity and musical design. Undoubtedly, the director was attempting to visually imitate his father. But I do not reproach the director; this is his second performance and I think he will still find his own directorial style and strengthen it. The most important thing for Kasymov will be to continue on his own path while still carrying on his father’s legacy and considering the meaning of the theater’s minimalist visual design and strong content component.

There has always been a shortage of actresses in Tajikistan’s theaters. However, there are great actresses—such as Sabohat Kasymova, Mavlona Najmiddinova, Mokhpaykar Yorova, Tereza Zaurbekova, and Soro Sobir. In modern Tajikistan, parents are reluctant to let girls into public professions, especially if it is connected with cinema, theater, or dancing.

Only girls whose parents are less demanding—or girls who do not have parents at all—continue with their passion for dancing and artistic expressiveness and eventually turn it into a professional craft. But there are very few of them in the country.

What is the future?

All Tajik theaters are run on a state budget. Accordingly, the state authorizes each theater’s repertoires. Although the state subsidizes theatrical institutions, these subsidies are not enough for the theaters’ expenses. Theaters are consequently trying to become more attractive to viewers and raise funds. The ticket prices are very low for theater productions here: $1 to $1.50 per adult ticket. I understand that the population is poor in Tajikistan; however, people are willing to pay money for the concerts of pop divas or other major events when the prices are as much as $50 or higher.

Someone told me that we have no theatrical atmosphere anymore. The circle of theater lovers has been diminishing. “The theater is dying,” I was told. I cannot agree with such a radical point. Theater, as a Phoenix, obtains new life by arising from the ashes. People will come back to theater as soon as they find themselves there, as proved by my experience watching the play Zavtra (Tomorrow) by Nikita Makarenko, staged by Ilkhom’s theater legendary director Artyom Kim. The feedback from the spectators/audience is crucial. Moreover, it is vital to discuss the performances, pose questions, and look for answers to them. Furthermore, aside from state support, it is paramount to get donations from donors and businesses.

I am optimistic about theatrical art in Tajikistan, and I agree with the words of the Zavtra’s scriptwriter Nikita Makarenko (the Ilkhom theater), who told me the following in our conversation in Tashkent: “Theaters remain a thriving center for contemporary culture/arts, and, as Ilkhom’s experience shows, they may survive and develop as unique places with their own exceptional spirit of freedom.”

Lolisanam has been an art manager in Tajikistan since 2000. She has contributed to writing and producing the nation’s first 3-D animation film, a short designed to promote awareness of environmental issues among children. She holds a Master’s degree from the University of Turin, Italy and an undergraduate degree in Russian Language and Literature. She was a Global Cultural Fellow at the Institute for International Cultural Relations at the University of Edinburgh and participated in the Central Asian-Azerbaijan (CAAFP) fellowship program at the George Washington University at Elliott School of International Affairs for Fall 2019.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia