News Desk

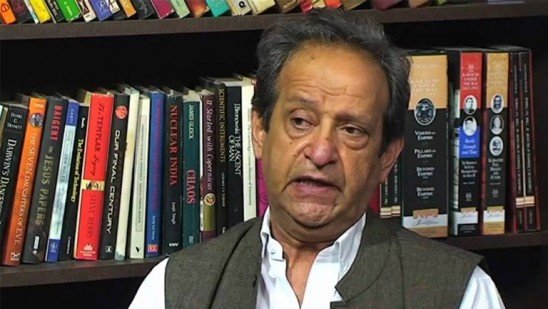

Aijaz Ahmad, a world-renowned Marxist philosopher and political commentator, passed away at his California residence on Tuesday (March 9). He was hospitalised for age-related ailments and had returned home only a few days ago.

Aijaz Ahmad was a literary theorist and in 2017 joined Irvine School of Humanities at California University where he served as a Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature.

Born in the Uttar Pradesh state of India in 1941, Aijaz moved with his parents to Pakistan following partition. After completion of education, he went on to work with various universities in the US and Canada before joining UC Irvine.

He was also an editorial consultant with Frontline magazine and served as a news analyst for the online site Newsclick.

Before joining UC Irvine in 2017, he was a professorial fellow at the Centre of Contemporary Studies, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, visiting professor at the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, and visiting professor of political science at York University, Toronto.

After the Second World War, nationalism emerged as the principle expression of resistance to Western imperialism in a variety of regions from the Indian subcontinent to Africa, to parts of Latin America and the Pacific Rim. With the Bandung Conference and the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement, many of Europe’s former colonies banded together to form a common bloc, aligned with neither the advanced capitalist “First World” nor with the socialist “Second World.”

In this historical context, the category of “Third World literature” emerged, a category that has itself spawned a whole industry of scholarly and critical studies, particularly in the West, but increasingly in the homelands of the Third World itself.

Setting himself against the growing tendency to homogenize “Third World” literature and cultures, Ahmad has produced a spirited critique of the major theoretical statements on “colonial discourse” and “post-colonialism,” dismantling many of the commonplaces and conceits that dominate contemporary cultural criticism.

In his book In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures, Ahmad primarily discusses the role of theory and theorists in the movement against colonialism and imperialism.

His argument against those who uphold poststructuralism and postmodernist conceptions of material history revolves around the fact that very little has been accomplished since the advent of this brand of postcolonial inquiry.

Writing from a consistent and sensible Marxist perspective, Ahmad criticizes the one-sidedness and posturing prevalent in so much hip academic postcolonial theory.

Although the book itself is not entirely free of the terrible use of language that is the hallmark of this theoretical approach, with the occasional “discourse”, “mapping” and “interrogating” making their appearance, Ahmad succeeds very well at dissecting the errors and bad faith that are at the core of the postcolonial enterprise in Western academia.

Ahmad notes that they tend to support the concept of ‘Third World literature’ or ‘Subaltern studies’, implying that there is a unity in the developing world that makes any text from there, or in some arbitrary manner associated with it, subversive and superior for that reason alone. This completely ignores the great differentiation in class, culture, politics and religion that exists within and between the various developing natures. It also utterly fails to properly analyze the position of given ‘Third World writers’ within this — Ahmad points to the case of Rabindranath Tagore, who is considered a canonical ‘Subaltern’ writer, despite the fact that within the context of Indian literature his works are considered conservative and elite.

Much of the book is taken up by a systematic study of the works of Fredric Jameson, Edward Said and Salman Rushdie in this context. He criticises Jameson for using the concept of the three worlds in such a manner that he conceives of the First as capitalist, the Second as socialist, and the Third as fundamentally neither.

Ahmad correctly objects that the Third is just as capitalist as the rest, but simply suffers more backwards capitalism and that therefore to read one ‘Third World literature’ of nationalism into the varied texts from these nations is to fundamentally misunderstand their political-economic position.

The book also contains a discussion of Marx’s articles on India, where Ahmad defends Marx from an all too easy reading of his works as Orientalist in the sense of Edward Said, whose many inconsistencies and contradictions with regard to his own position on the ‘Third World’ he deftly exposes.

Ahmad in his book expresses his chagrin at how his critique of Jameson has been appropriated by postcolonial scholars as an attack on Marxism, while Ahmad contends that he takes issue with Jameson simply because of his use of Marxism in the essay on Third World Literature is not rigorous enough.

The book also contains a lengthy critique of Edward Said’s Orientalism which Ahmad argues reproduces the very liberal humanist tradition that it seeks to undermine in its selection of Western canonized texts that are critiqued for their Orientalism, as this upholds the idea that Western culture is represented in its entirety through those very texts.

Furthermore, Ahmad asserts that by tracing Orientalist thought all the way back to Ancient Greece it becomes unclear in Said’s work whether Orientalism is a product of Colonialism, or whether Colonialism is, in fact, a product of Orientalism.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia