Muhammad Ali Sadpara, who went missing on K2 on February 5, 2021, will be remembered as a hero for his courage and feats, writes M Ilyas Khan, an Islamabad-based senior journalist and correspondent for BBC News.

Muhammad Ali Sadpara, a versatile mountaineer, is the only Pakistani to have climbed eight of the world’s 14 highest mountain peaks, and he made the first-ever winter ascent of the world’s ninth highest peak, Nanga Parbat.

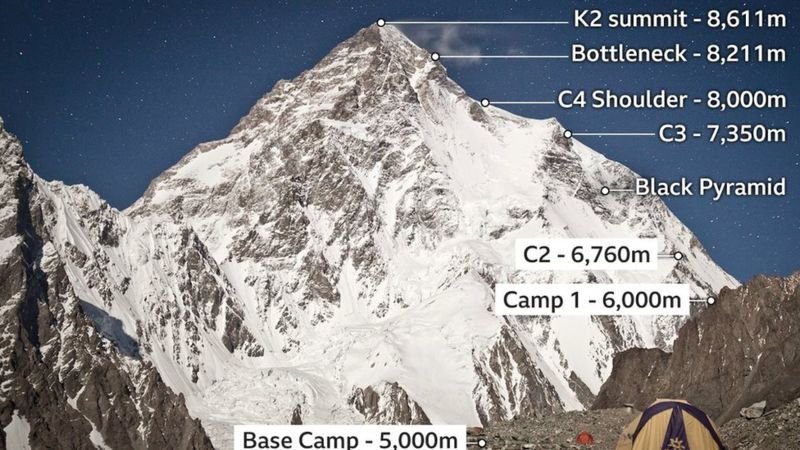

On Friday, 5 February, he went missing along with two others — Iceland’s John Snorri and Chile’s Juan Pablo Mohr — while trying to climb K2, the world’s second-highest peak at 8,611m (28,251 ft) and also reputedly the deadliest.

His son Sajid was also a member of the team and the idea was for the father-and-son duo to summit K2 without oxygen, a feat never done before in winter. But Sajid had to turn back from a spot called the Bottleneck – also known as the “death zone”, some 300 metres from the top – after he felt sick.

He has since helped military-led rescue teams scour the mountain for signs of his father and the other two men – but there has been no trace of any of them. The military want to resume the search, weather permitting, using a high-altitude C-130 aircraft and infrared technology to spot possible shelters on the peak.

But Sajid doesn’t hold out much hope.

“I’m thankful to everyone organising a search, but it’s unlikely that they are alive by now. So the search should be to recover their bodies,” he said earlier in the week.

Who is Muhammad Ali Sadpara?

Muhammad Ali was born in 1976 in Sadpara, a village in one of the river valleys of Baltistan region in Pakistan’s extreme north.

Livestock farming is the main source of livelihood in the region, and the area’s youth also work as porters with Western mountaineers and adventure tourists who frequent the region each year.

Ali Sadpara finished middle school in the village and his father, a low-grade government employee, later moved the family to Skardu town, where he studied up to higher secondary school before moving onto climbing.

Nisar Abbas, a local journalist and relative and friend of Sadpara from their village days, describes him as being extraordinary right from his childhood.

“He had the physique and the habits of an athlete, and was also good in studies. He never failed a class. Since his elder brother never did well in school, his father was keen to get him a good education and that’s why he moved him to Skardu.”

Given the family’s financial constraints, he moved to climbing in around 2003 or 2004.

“He was an instant success with tour operators because the expeditions he led were mostly successful. He earned worldwide fame in 2016 when a three-man team he was a member of became the first to summit Nanga Parbat in winter.

Hamid Hussain, a Karachi-based tour operator from Skardu who has known Sadpara since 2012, has similar memories.

“He was brave, and pleasant and very friendly,” he recalls. “And he was so physically fit. We trekked together on many occasions, and while there were times when we would run out of breath and collapse, he would still jog up the steep slopes and then shout back at us, asking us to be quick.”

On one occasion in the winter of 2016, during a trek from Sadpara valley to the Alpine planes of Deosai, when freezing winds caught them in a snow-filled gorge and sent shivers down their spines, they saw him climb smoothly up the slope and start dancing over the ridge.

In the last three years, Ali Sadpara had been travelling to France and Spain to train college and university students in mountaineering.

Why summit K2 without oxygen?

One theory is that he was working as a high-altitude porter for John Snorri and had to comply with the agreement he had signed with him.

But that was just a ruse, Nisar Abbas says. Weeks earlier, Ali Sadpara had openly expressed his keenness to make the attempt after a 10-member Nepalese team led by the famous Sherpa Nirmal Purja became the first-ever to summit K2 in winter.

And in order to set a new record, Sadpara wanted to do it too – but without oxygen. And he also wanted his son to be there when it happened.

Sajid, his son, told the media that they had started out with some 25 to 30 climbers, local and foreign, but all of them turned back before hitting the 8,000-metre point.

Sajid’s own condition worsened when they hit the Bottleneck.

“We had carried an oxygen cylinder in our emergency gear. My father told me to take it out and use some. It will make me feel better.”

But while Sajid was setting up the cylinder, its mask regulator sprang a leak.

Meanwhile, his father and the two foreigners continued to scale the Bottleneck. His father then looked back and shouted to Sajid to keep climbing.

“I shouted that the cylinder had leaked. He said, ‘don’t worry, keep climbing, you’ll feel better’. But I couldn’t gather the strength to do it and decided to turn back. It was around noon on Friday. That was the last I saw of them.”

When asked why his father insisted that he keep going, Sajid said: “The Nepalese had done it weeks earlier, and he wanted to do it too, because K2 is our mountain.”

What could have happened?

Sajid says he saw the three men climb over the bottleneck at the top, which means that they probably did make it to the summit.

Experts say most accidents happen while descending, as even a slight loss of balance can send one crashing down into an abyss.

Those who knew Ali Sadpara doubt he would have made such an error.

People in his village still recall more than one occasion when a goat Ali Sadpara was tending in the mountains got injured, and instead of slitting its throat, as others would, he’d haul it over his shoulders and walk all the way down to take it to the village vet.

They suspect that he probably failed to make it back because one or both of his partners met with an accident and he stayed on trying to find a way to save them.

We will probably never know.

People in the area have been awaiting a miracle.

But as his son says, given the hostile environment, low oxygen and winter temperatures dipping to as low as -80C, there’s little chance the men could have survived a week at over 8,000m.

“This hasn’t happened in climbing history, so we can only hope for a miracle,” Sajid Sadpara told the BBC.–Courtesy: BBC News

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia