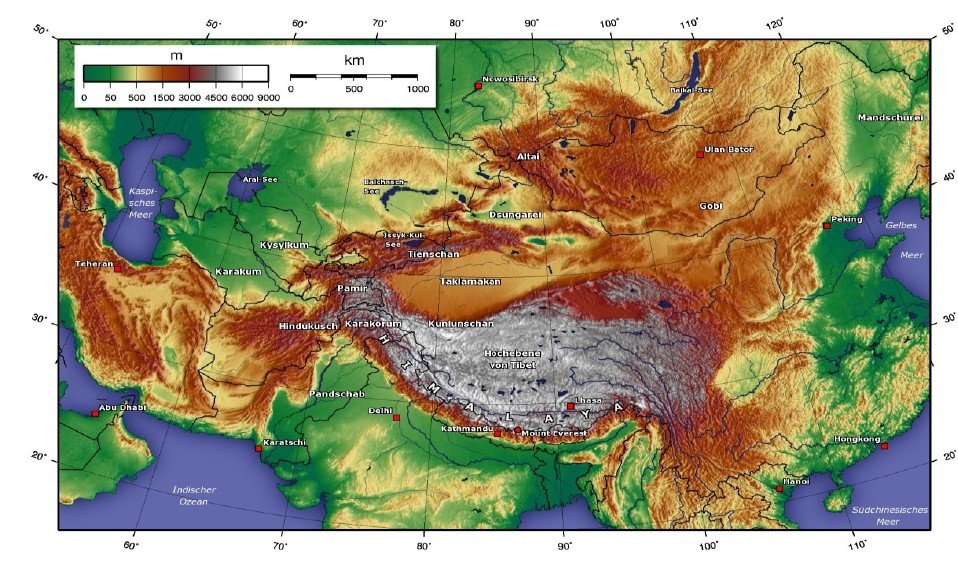

Central Asia is a landlocked region comprised of rugged mountains spanning from Tian Shan and Pamirs to the vast Karakum and Kyzylkum deserts, and the fertile valleys of the Fergana Basin. Stretching over five countries with diverse geography, Central Asia has been the hub of ancient Silk Road trade connecting China with West Asia, South Asia and Europe.

In this article I will discuss the often-overlooked annexation of Central Asia by the Russian Empire with special focus on Pamirs and signify its importance in the context of the Anglo-Russian competition that resulted in its integration into the broader Russian Imperial narrative of ‘Great Reforms’. This annexation was a complex interplay of colonisation and social transformation that reconfigured the diverse cultures and politics of the region.

The history of Central Asia is an ornate tapestry that may help to understand the dynamics of the empire, control and resistance in the 19th century. Owing to its geographical importance and resource riches, it has been a cultural and trade channel between civilisations for centuries. The mountains, deserts, and khanates of Central Asia became the chessboard of the imperial geopolitical rivalry, famously known as the ‘Great Game’ of the 19th century between the British and the Russian Empires. The former wanted to protect its Indian colony from Russia, which aimed to expand its territory and influence into Central Asia.

The rivalry ended with the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, which drew spheres of influence in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet. While the term ‘Great Game’ originated in the 19th century, it is often used as a metaphor for later competition between the US and Europe and the defunct Soviet Union during the Cold War and the Afghan conflict, as well as China today.

The Pamirs are like a crown emerging from the heart of Asia by its snow-capped peaks, splitting the sky at altitudes where clouds swirl below, and breath comes short. Often called ‘as ‘Baam-i-Dunya’ (Roof of the World) in Persian, this high plateau has been more than a geographical phenomenon where the Kunlun, Tian Shan and the Karakoram meets the Hindu Kush and the western Himalayas.

This labyrinth of passes and valleys has funnelled invaders, spies, explorers, monks and traders for centuries. Deep gorges through eternal rocks are carved by the Oxus (Amu Darya) and the Panj or Syr Darya, where ibex and yaks cling to steep slopes that are impossible to tread by human feet. In the thin air of places like Wakhjir Pass and Lake Zarkul, history seems frozen even though the destinies of nations have been decided here.

For much of recorded history, the Central Asian and High Asian landscapes have always remained resistant to easy mastery. The oasis cities of Tashkent, Samarkand, and Bukhara thrived on silk routes linking China to Persia while its vast Great Steppe faced ramming by nomadic horsemen. In the 19th century, these ancient canvases became the theatres of deception, conspiracy, and intrigue. For Russia, the Pamirs were the ultimate prize due to its strategic vantage over British India, Afghanistan, and China. This rivalry and its transformation into a buffer zone ultimately evolved into a full conquest, forming the resettlement and a venue of conflict that still resonates in the 21st century. Today, as Russia, China, India, Afghanistan and Pakistan scramble anew for control of resources, connectivity and borders; the rivalry still continues, casting a long shadow over global power rivalries.

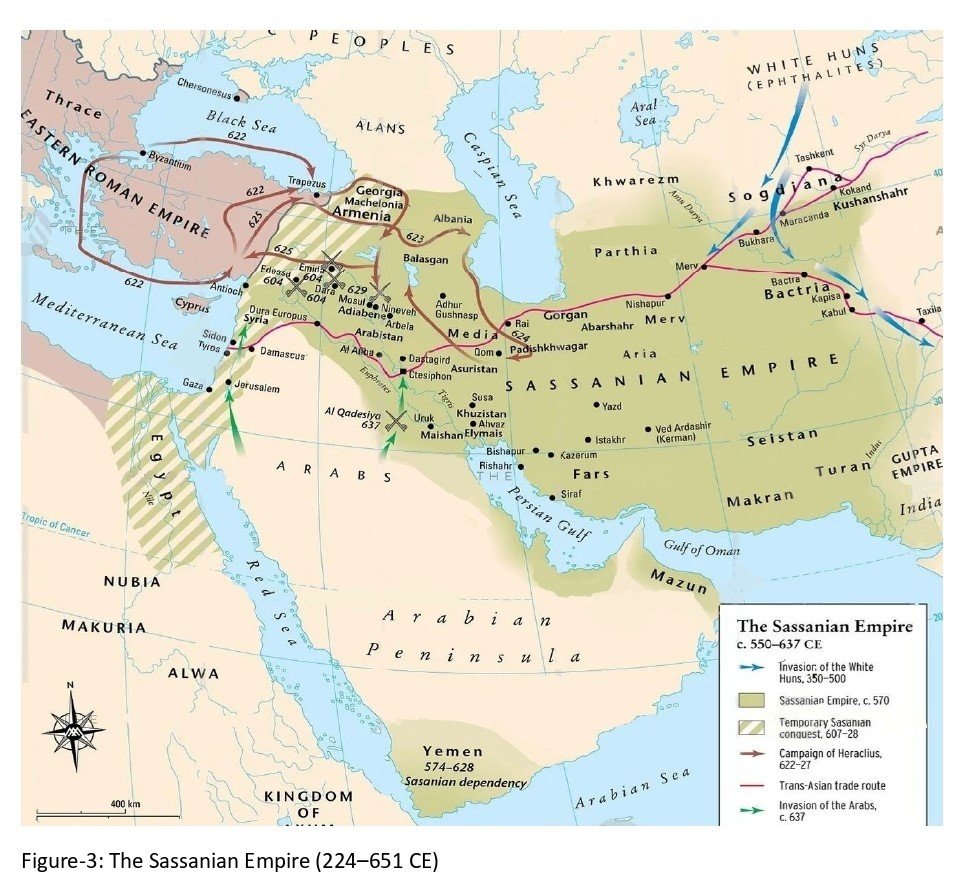

Ancient Empires

The map below illustrates the Sassanian Empire under Khosrow II stretching from the Indus Valley to the Egypt, an area that was once Achaemenid Empire. The modern struggle in Central Asia begins by the Mongol’s conquest that fractured the region into two major states of Transoxania and eastern oasis to Chagatai and Dasht-i-Qipchaq/Kazakhstan to Joshi’s Ulus. By 14th century, Mongols started converting to Islam like Özbek Khan of the Golden Horde (r. 1313–1341). After a kurultai assembly in 1370, Taimur emerged from the Barlas tribe proclaiming Balkh’s sovereignty that was extending over Mesopotamia and the Punjab (mostly of now-a-days Pakistan).

The Timurids were overthrown by another Changezi Shaybani Khan in 1507, but Tuqay-Timurids (Janids/ Ashtarkhanids) took over in 1599 resulted in three khanates of Bukhara, Khiva, and Kokand traversing Persia, Afghanistan, Caspian Sea, Kazakh, and China in 1709. These khanates struggled to dominate each other. For instance Rahim Khan I (1806-1825) of Khiva succeeded over Turkmen tribes of Yomut and Teke, power restoration by Amir Nasrullah (1827-1860) of Bukhara, Umar Khan and Ali Khan (1810-1842) of Kokand.

Meanwhile the Kazakh steppe was fragmented into three Zhüz following the death of Tauke Khan in 1715. In a struggle to stop Dzungar invasions (1723-1727), Zhüz ruler Abul Khair Khan sought Russian protection in 1731 followed by many of his successors till 1740s which also resulted in emergence of Russian forts of Omsk (1716), Semipalatinsk (1718), and Kamenogorsk (1720).

The Kyrgyz under Arman Khan, despite of beheading various rebels, were pushed south by Dzungars, finally submitted to Kokands and Tian Shan while Turkmens were conquered by the Russians.

The Crimean Spark and Alexander II’s Reforms

Humiliating defeat of Russia in Crimean War (1853-1856) ignited the Central Asian rivalry between Russia and Britain, also exhibiting the backwardness of Russian Empire as Nicholas I whispered to son Alexander II, the next emperor, “I hand you command not in good order”. Alexander II ascended the throne and had to bring reforms (1861-1874) in education, justice system, local government, reducing mandatory military service from 25 to 6 years, and emancipation of 40 million serfs after exposing technological lag in Russian defence in the fall of Sevastopol. The war and the Paris Treaty (1856) redirected the Russian ambition to south. It turned to Central Asia under the commandership of Dmitry Milyutin. This also provided a narrative of Crimean revenge without a conflict with the Europeans and enabled the empire to threaten British India through the passes of Pamir.

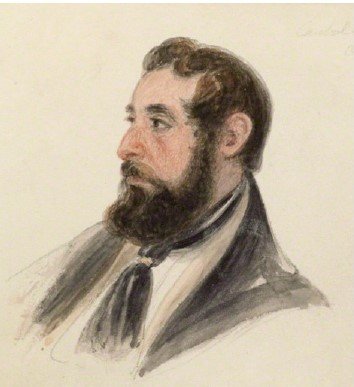

It was due to the mission of Captain Arthur Conolly (1807-1842), a British intelligence officer that Russians looked seriously at Pamir. Conolly was the person who coined the term, “Great Game”. He rode to Bukhara in 1840 as a move to unite three khanates against Russia when Amir Nasrullah Khan beheaded him in 1842 along with Col Charles Stoddart.

The Russian Conquest of Steppes

Russia launched military campaigns simultaneously at different parts of divided Central Asia in 1850s marked by storming of Col Johann Blaramberg on Kokand’s Ak-Mechet Fort in 1853 who renamed it Fort Perovsky (now Kyzylorda). Tokmok town was taken by Col Apollon Zimmerman in 1859 while the control of Uzun-Agach Pass was taken by Col Gerasim Kolpakovsky in 1860. In 1864, the final push emerged with the conquest of Tashkent by Mikhail Chernyaev getting help from Orenburg Column of Nikolai Kryzhanovsky despite Alexander’s disapproval.

The capture of Jizzakh and Khujand followed by Dmitry Romanovsky in 1866 who replaced Chernyaev. Although Emir of Bukhara, Muzaffar declared holy war (ghazwaat), he was defeated by Kaufman in 1868 resulting Bukhara as a vassal forcing it to pay tribute to Russia. Kaufman also gained control of Samarkand and Khiva in 1873.

Kokand also fell in 1876 due to the 1875 Revolt led by Mulla Essa Ali and Abdur Rehman Aftobchi against the tyranny of Khudayaar Khan and became Fergana Oblast due to Skobelev’s storming of Andijan. Turkmenia, on the other hand, showed long resistance, but Skobelev captured Geok-Tepe in 1881. It was followed by the fall of Tejen in 1883, Merv in 1884, and Panjdeh in 1885, consolidating the victory of Komarov over Naib Salar Taimur Shah. (To be Continued)

Dr Zahid Usman is a multi-disciplinary practitioner and educator from Swat Valley. His work as an architect, urban and regional planner, and lighting designer is grounded in spatial planning, large-scale master planning, heritage conservation, infrastructure development, and community development. He is dedicated to developing integrated solutions that balance socio-economic, environmental, and cultural factors. A graduate of the National College of Arts (NCA) Lahore, University College Borås, KTH Stockholm, and International Islamic University Malaysia, Usman now teaches at his alma mater, the NCA, and maintains an active research agenda focused on mountain heritage. He can be reached at: xahidusman@gmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia

3 thoughts on “An illustrated chronicle of the Anglo-Russian contest in Central Asia”

Mashallah Zahid Usman bhai

It is very informative research

Proud of you

This is a remarkably comprehensive chronicle that skillfully weaves together the geographic, political, and military dimensions of the Great Game in Central Asia. The author’s multi-disciplinary background shines through in the detailed topographical context and the systematic documentation of Russian expansion through the khanates. The historical progression from ancient empires through the Crimean War to the systematic conquest of the steppes is well-structured and richly illustrated with maps and portraits. However, the article ends abruptly with “To be Continued,” leaving readers eager for the next installment, particularly regarding the Pamir campaign itself which is promised in the title. Overall, Dr. Usman has created an accessible yet scholarly piece that makes complex 19th-century geopolitics understandable for contemporary readers interested in understanding today’s Central Asian dynamics.

This is a remarkably comprehensive chronicle that skillfully weaves together the geographic, political, and military dimensions of the Great Game in Central Asia. The author’s multi-disciplinary background shines through in the detailed topographical context and the systematic documentation of Russian expansion through the khanates. The historical progression from ancient empires through the Crimean War to the systematic conquest of the steppes is well-structured and richly illustrated with maps and portraits. However, the article ends abruptly with “To be Continued,” leaving readers eager for the next installment, particularly regarding the Pamir campaign itself which is promised in the title. Overall, Dr. Usman has created an accessible yet scholarly piece that makes complex 19th-century geopolitics understandable for contemporary readers interested in understanding today’s Central Asian dynamics.