by Aftab Husain

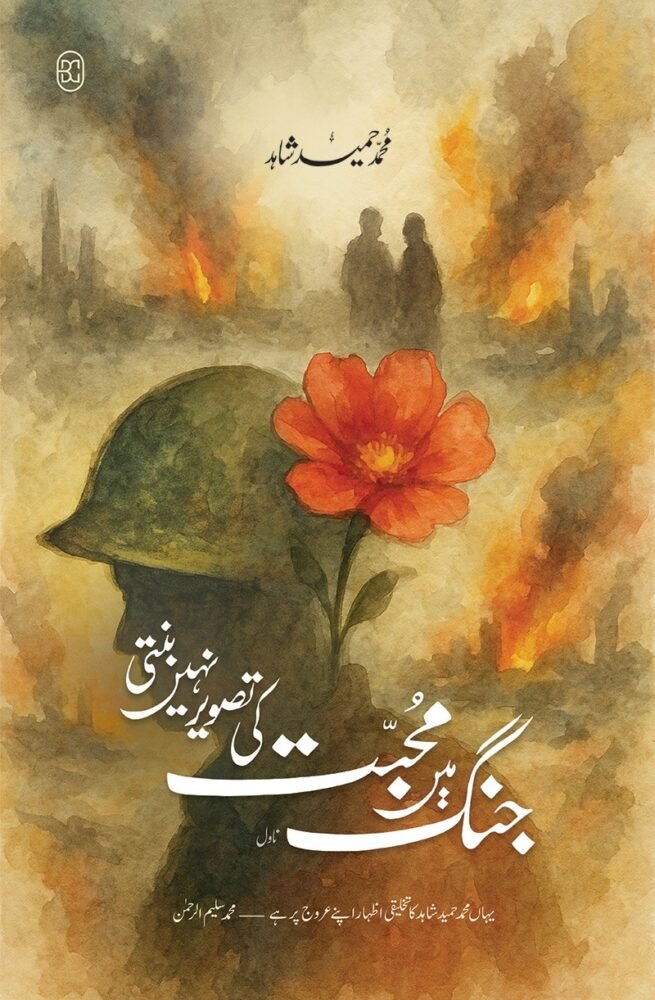

The novelette Jang Mein Muhabbat ki Tasveer Nahin Banti resists the very tradition of war literature it appears to inhabit. On its surface, it tells of lives destroyed and distorted in the crucible of violence, but beneath that surface runs an unrelenting interrogation of storytelling itself—what it means to narrate love when war is the backdrop, what it means to “represent” horror when representation itself falters. The very title, a declaration that “a picture of love cannot be drawn in war,” sets the stage for a work that is less a chronicle of events than an inquiry into the limits of narrative and representation.

From its earliest pages, the text destabilises the expectations of the reader. We are not given a linear progression of characters whose destinies unfold before us in realist clarity. Instead, we are drawn into a shifting narrative terrain where the act of narration is constantly foregrounded. Gérard Genette once observed that “narrative does not simply recount events; it frames them, it makes them visible and thinkable.” In this novelette, that framing is itself interrogated, broken, and reconstituted. The narrator does not only recount lives entangled in war; he also interrupts himself, questions his authority, and insists that what is being told may not be “truth” at all but the echo of countless other voices, fragments, and texts.

The text is profoundly metafictional. At multiple points, the narrator declares that he is aware of writing a story, aware of shaping an audience’s response, and aware of the impossibility of capturing in words what trauma does to human life. The boundaries between the world of fiction and the world of the reader collapse, and what remains is an oscillation, a ceaseless reminder that literature is both a window and a mirror, both a veil and an unveiling. In that sense, the novelette becomes not simply about war and love, but about the writing of war, the impossibility of writing love in war, and the paradox of literature’s attempts to testify.

Intertextuality saturates the work. Julia Kristeva reminds us that “any text is a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another.” Here, stories of individual suffering are never singular—they echo myths, folk tales, fragments of oral histories, and the residue of countless other war narratives. The narrator is less an “author” than a conduit through which multiple cultural and literary voices pass. In one moment, the intimate suffering of a woman becomes indistinguishable from the mythic figure of sacrifice; in another, the death of a soldier is refracted through literary allusions that extend beyond the local to the universal. The text never allows us to forget that each voice is always already haunted by other voices, that representation is always citation.

What emerges is a self-consciously fractured narrative that resists closure. War, after all, is not a story with a beginning, middle, and end—it is repetition, recurrence, an endless return of violence. The novelette mirrors this by refusing neat narrative arcs. Characters are glimpsed and then abandoned, their stories begun and then broken off. The narrator himself becomes unreliable, sometimes confessing ignorance, sometimes acknowledging invention. The metafictional texture forces the reader into an ethical stance: not to consume the story as spectacle, but to question the very act of consuming war and love as literature.

At its heart, the text stages the encounter between love and destruction, intimacy and history, body and discourse. And yet it does not romanticise this encounter; rather, it insists that love under the conditions of war cannot remain untouched. Here, Genette’s concept of narrative levels becomes crucial. The “story” of war and love unfolds within the “discourse” of the narrator, but the narrator also comments on the impossibility of that discourse. There are layers upon layers, and the reader is constantly being pulled out of immersion to reflect on these layers themselves.

The thematic spectrum of the novelette is as wide as it is unsettling. While war and love appear as the central axes, what unfolds across the narrative are themes of fragmentation, memory, violence, displacement, and the persistent search for meaning amid devastation. The text meditates on the vulnerability of the human body, the unreliability of memory, and the collapse of moral boundaries in a world governed by survival. Desire is shown to be inseparable from destruction, intimacy from estrangement. In this way, the text opens itself to philosophical questions that far exceed the immediate experience of conflict, situating itself within a broader meditation on the precariousness of human existence.

At times, the text approaches allegory, but even allegory falters in the face of atrocity. We are shown bodies that cannot be reduced to symbols, grief that resists all metaphor. There is in these passages a pulsating undercurrent beneath language itself, as though words tremble under the weight of what they cannot fully articulate. The narrative becomes stammer, rupture, silence. What is written is as significant as what is left unsaid.

This refusal of closure, this insistence on the impossibility of seamless representation, is what makes Jang Mein Muhabbat ki Tasveer Nahin Banti a philosophical text as much as a literary one. It asks: how does one speak of love when language itself has been mutilated by war? How does one narrate trauma when trauma is precisely the shattering of narrative coherence? The metafictional intrusions, the overt intertextuality, the self-conscious layering—all serve not to ornament but to embody this crisis of narration.

The narrator becomes both participant and observer, victim and author, voice and silence. At times he speaks in a tone of confession, at times in the cold distance of report. This oscillation is itself part of the philosophical thrust of the work: that there can be no singular perspective on war, no singular voice of truth. Truth is fractured, refracted, plural. Literature cannot capture it whole, but it can stage the impossibility of its capture.

The intertextual currents extend further into cultural and political critique. The text situates itself in the long tradition of South Asian war writing, but it also dialogues with global traditions of metafiction, from the self-reflexivity of Borges to the testimonial fractures of Primo Levi. In doing so, it refuses the insularity of “national” literature and insists on the global resonance of local trauma. War is both particular and universal; love is both embodied and displaced. Each story told is already entangled with countless others across history.

And yet, for all its philosophical density, the novelette does not lose its human pulse. At its most searing moments, it offers fragments of lives—women waiting, men broken, children orphaned. These fragments are never allowed to cohere into a sentimental whole. They remain fragments, reminders of incompleteness. The metafictional gestures serve to keep them in fragments, resisting the aesthetic temptation to make of suffering a coherent, consumable story.

Jang Mein Muhabbat ki Tasveer Nahin Banti should be read not only as a story but as an inquiry into storytelling, not only as a narrative but as a critique of narration

Aftab Husain

This is where the text most forcefully achieves its ethical power. It does not allow the reader the comfort of catharsis. It does not permit the illusion that love can redeem war, or that war can be subsumed into the redemptive arc of love. Instead, it insists that the picture of love in war cannot be drawn—not because love vanishes, but because war contaminates the very act of representation. The impossibility is not in love itself, but in narrating love without distortion.

Thus, Jang Mein Muhabbat ki Tasveer Nahin Banti should be read not only as a story but as an inquiry into storytelling, not only as a narrative but as a critique of narration. Its metafictional ruptures and intertextual mosaics embody the philosophical crisis of representation in the age of war. It is less an answer than a question, less a picture than a shattered mirror in which countless faces flicker.

The novel ends where it began, in uncertainty, in refusal. And this refusal is its philosophical gift. It reminds us that narrative is never neutral—it is always a choice, a frame, a cut. It reminds us that no text speaks alone—each is a chorus, a palimpsest, a dialogue across history. And it reminds us, above all, that in war the very act of love, like the act of writing, becomes a fragile defiance, an impossible possibility.

Muhammad Hameed Shahid, one of the most significant contemporary voices in Urdu fiction, has long been preoccupied with themes of violence, existential fracture, and the limits of human endurance. His works stand at the intersection of political urgency and philosophical depth, always pushing Urdu prose toward new formal and ethical horizons. This novelette, his latest work, is a culmination of these concerns—at once intimate and universal, experimental and searingly human. With it, he confirms not only his place within the canon of modern South Asian literature but also his dialogue with the global philosophical novel.

Dr Aftab Husain is a Pakistan-born, Austria-based poet who crafts verse in Urdu and English. His work bridges cultural and linguistic landscapes. He is a scholar of South Asian literature and culture, which he teaches at the University of Vienna.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia