By: Reshma P. Musofer

Educational reforms and a ‘single-national curriculum’ have lately become a widely debated topic in Pakistan and across the globe. However, little effort has been made to respond to the practical challenges pertaining to ways of enactment and imparting education.

My recent research paper as part of my PhD thesis, published in Curriculum Journal, is an effort to explore the enactment of educational reforms, specifically the Australian Curriculum that was conceived in 2008 and implemented in schools from 2010.

The study was conducted in one State High School that had been implementing the new curriculum for five years by the time data was gathered for this study in 2015.

The main argument is that curriculum reforms at the national level and its enactment in schools is a top-down approach not necessarily a reflection of the intended curriculum.

But first it is important to differentiate between ‘implementation’ and ‘enactment’ in relation to educational reforms.

In implementation research, scholars measure how much of an intended/documented curriculum has been implemented. In other words, it is a measurement of how the documented curriculum is used or implemented effectively in schools.

It is a top-down approach, which makes teachers strictly accountable and leaves no room for their autonomy. Whereas enactment research believes that the intended or documented curriculum doesn’t need to be implemented in its totality. Instead, enactment research believes that schools have their own social, historical, and geographical context and that one box cannot be fit for all contexts. That a single national or standard curriculum cannot address the contextual needs of all schools across a country.

The contextual differences in schools, the experiences and expertise of teachers’ and leadership, the historically evolving practices, and the diversity in the students’ composition put a question mark on one standard curriculum as a one size fits all.

The notion of enactment believes that schools have their own resources, existing practices that have worked well and teachers’ expertise to address the diverse needs of students, making curriculum enactment an active and creative process.

As the curriculum works in coordination with the local factors to make learning more meaningful and useful, therefore, measuring the fidelity of implementation is not as effective as making the curriculum contextually relevant.

Another argument in this space of the top-down approach in curriculum implementation is that the standard national curriculum is generally developed and approved by ‘experts’ in the field. These expert policymakers might not have the experience in teaching in schools, so they generally cannot see the curriculum through the lens of teachers’ experiences rather rely on the global forces borrowing policies from other countries.

Hence, the purpose of this research was to analyse the curriculum through the experience of the teachers who actually bring the curriculum to life by teaching it.

In my data analysis, I used the theory of a French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu’s concepts of field, habitus and capital are very well researched in many different fields like economics, sociology, politics, religion, and education.

There are many related concepts associated with these bigger themes such as position-taking, position-taking strategies, doxa, and symbolic violence. In this paper, I have particularly focused position-taking along with field, and habitus.

The field is a network of positions. People or Bourdieu refer them as agents, occupy certain positions based on the field structure and the capital they possess. A field, such as political field, economic field, or educational field, has agents who occupy certain spaces. By objectively defining the field of research, one becomes capable to go down deeper and analyse these positions further.

Agents occupying different positions, also have dispositions or habitus which is the social world within the biological body of individuals. This internal world or habitus starts developing very early from home. As the child internalises the norms and values from home; s/he moves to the outside world and keeps internalising things from the surrounding like streets, playgrounds, or religious places.

One important organization is the school. In schools, the habitus is influenced the most through deliberate teaching of a certain curriculum. As the child grows, s/he gains more experience or understanding through these organizations. Some dispositions are replaced with new experiences while others remain durable.

Thus, the habitus is flexible – it can expand, it can forget some past experiences, but it can also gain more experiences. Bourdieu argues that habitus is potential and not always durable.

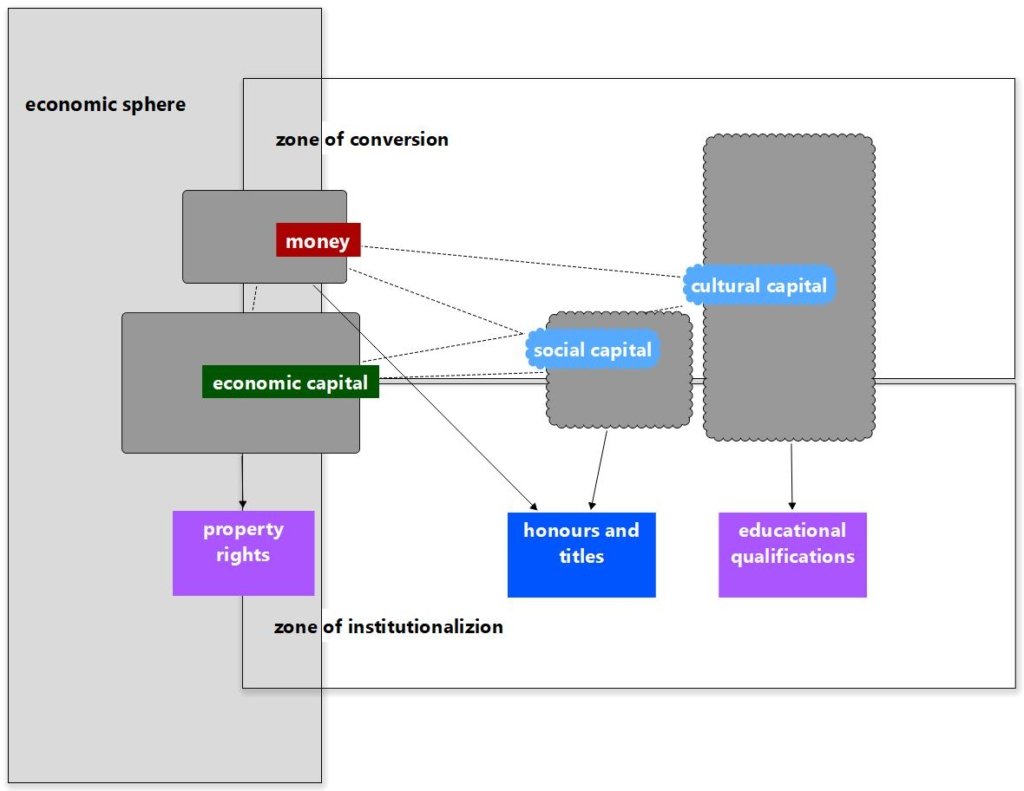

The third concept is capital. There are different kinds of capital like economic capital, cultural capital, and social capital. Bourdieu states that these capitals are interchangeable especially many of them can be converted into economic capital. The agents’ position in a field is determined by the kind and proportion of the capitals they possess.

Symbolic capital is when it is valued and legitimized in a field more than other capitals. For example, speaking of English might be a symbolic capital in the job market in a country.

Hence, agents in any field, occupying a specific position have many invisible and deep traits that determine their relationship with other positions in the field. In any field, agents take a position based on what they already know, their habitus and the kind and proportion of capital they possess. This is called position-taking.

Thus, in Australia, there was a visible change in the education field with the introduction of the new national curriculum. The field was changing and demanded a change in the teachers’ habitus. However, this change in the habitus was not easy. In other words, the enactment of a curriculum or any educational change is not a straightforward process.

There is no short cut to it. Instead, the enactment is a long process where teachers go through the new reform, trying to make sense of what is changed. They develop new resources, but they also have existing resources that they do not want to let go because those existing practices and resources have worked very well for them. Sometimes they find out that the new resource is not working, hence, they modify or change it. They use trial and error method, rely on their durable habitus while trying to change according to the changes in the field.

In this process of implementing, reflecting, falling back on their previous practices, consciously or unconsciously using their durable disposition, teachers were in a flux of moving forward but relying on their past. This continued for a few years during the enactment process.

Hence, my argument is that during the first few years of education change enactment, teachers do not necessarily arrive at a position-taking point. Rather they are in a position-making process of what works well for them and what they need to change, how much, for how long, with what kind of resources and tools.

Policymakers must keep in mind the fluctuating situation of the implementation stage while planning changes in policy. It is important to understand the local context, its challenges but also acknowledging its creative ways of navigating a new change. This is a good strategy for managing a crisis situation and change.

Dr Reshma Perveen Musofer is a teacher by profession, she did her PhD from the University of Queensland, Australia, and working as a research fellow in STEM education for schools at the same university. She tweets @ReshPar

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia