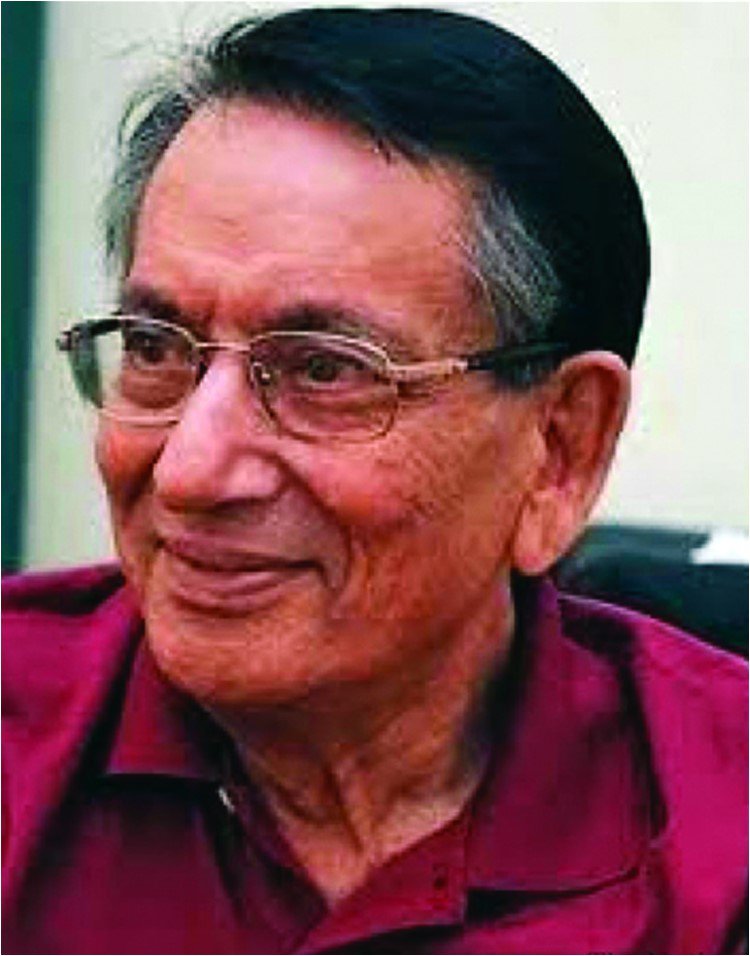

Raza Naeem offers a translation in which the late Enver Sajjad (1935 – 2019) writes about himself and his art

Translator’s Note: One of Pakistan’s last true Renaissance men, writer, novelist, artist, actor, dancer and playwright, Dr Enver Sajjad passed away on June 6 last week. He was on e of the last Pakistani writers who wrote fiction of an international calibre and was known in equal measure both in India and Pakistan. Along with the likes of his late Indian contemporary Balraj Menra, Sajjad was known for being one of the founders of abstract and symbolic fiction, perhaps one of the rare members of the Progressive Writers Association to do so. According to this writer, his Urdu translation of Soviet writer Emmanuil Kazakevich’s little-known account of Lenin’s revolutionary days ‘The Blue Notebook’ (1982) and his experimental novel ‘Khushiyon ka Bagh’ (1979) will stand out as his everlasting literary legacies for posterity. I also think his prescient essay on the definition, dynamics and discontents of Pakistani culture, “The ‘Issue of National Character and Culture’ and Judicious Mismanagement”, which forms part of his essay collection, ‘Talaash-e-Vujood’ (1986) and written at a very important time in Pakistan’s history deserves a rereading in Naya Pakistan. Keeping in mind the demands of shortage of time and space, and the requirements of currency, and while we await a fuller evaluation of his talents from his contemporaries and critics, I thought to translate his Preface to the aforementioned essay collection as perhaps the best representation of his eventful artistic life, rather than a conventional obituary, which might do him considerable injustice. This original translation (to my mind and knowledge, the very first translation of any of his works in English) not only sums up Sajjad’s person and views on art but for the uninitiated, and especially for our younger generations, by way of advice to all budding writers, serves as an entry point to a further and deeper engagement with his works

e of the last Pakistani writers who wrote fiction of an international calibre and was known in equal measure both in India and Pakistan. Along with the likes of his late Indian contemporary Balraj Menra, Sajjad was known for being one of the founders of abstract and symbolic fiction, perhaps one of the rare members of the Progressive Writers Association to do so. According to this writer, his Urdu translation of Soviet writer Emmanuil Kazakevich’s little-known account of Lenin’s revolutionary days ‘The Blue Notebook’ (1982) and his experimental novel ‘Khushiyon ka Bagh’ (1979) will stand out as his everlasting literary legacies for posterity. I also think his prescient essay on the definition, dynamics and discontents of Pakistani culture, “The ‘Issue of National Character and Culture’ and Judicious Mismanagement”, which forms part of his essay collection, ‘Talaash-e-Vujood’ (1986) and written at a very important time in Pakistan’s history deserves a rereading in Naya Pakistan. Keeping in mind the demands of shortage of time and space, and the requirements of currency, and while we await a fuller evaluation of his talents from his contemporaries and critics, I thought to translate his Preface to the aforementioned essay collection as perhaps the best representation of his eventful artistic life, rather than a conventional obituary, which might do him considerable injustice. This original translation (to my mind and knowledge, the very first translation of any of his works in English) not only sums up Sajjad’s person and views on art but for the uninitiated, and especially for our younger generations, by way of advice to all budding writers, serves as an entry point to a further and deeper engagement with his works

***

Man is so obsessed with classification – meaning homogenization – that if he cannot stick a label on any discovery, cannot fit it into one’s frame, he deems it meaningless or worthless, closing the doors of research and inquiry on it. Then sometimes some rebel arrives, picks it up after dusting off the new discovery of that time, evaluates it and if that discovery does not fit the customary principles, he then creates principles to give a status to that discovery. The world of art is indeed very different and here the entire arrangement is fluid and there is great room in its logic. But the scientific world too is full of rigid dogmatism. It cannot be said conclusively whether this attitude is due to the entry of limited perception or mere negligence. I always view homogenization with suspicion in that this method gives rise to commodification and encourages those who fill prominent brands of bottles with their self-prepared beverage from home.

I write stories and for this I have to work really hard and I do not dare invent rare ideas, in that between the Unseen and myself there is a human. I can humanize the Unseen but cannot unsee the human; I do not come within the range of Divine inspiration. With the qualities of my weaknesses, deficiencies, virtues, energies and generosities, defects, I am an ordinary person. I am grateful that I do not consider myself faultless otherwise I would have become a victim of hysteria, trying to have my first weak volume (of short stories) accepted indeed as if it were some Divine revelation. In every story, there is just this much of an attempt from my side to be successful in somehow maintaining that deep, delicate dialectical balance between the topic (idea) and form which will destroy the order of the story if one of its scales even bends just a fraction. In this connection, I have to work even more. Faulkner says that no story in the world is new, only the tone and style is. I am not so short-sighted and foolish as to disagree with this truth of Faulkner.

“Enver Sajjad is the great architect of the new Urdu afsana” (Shamsur Rahman Faruqi)

This proves the large-heartedness of the opinion-maker and I respect this encouragement.

“What a big fr aud Enver Sajjad is. He cannot narrate a story. He is not a man of the story indeed.”

aud Enver Sajjad is. He cannot narrate a story. He is not a man of the story indeed.”

I also do not dismiss this learned opinion and I respect this narrative and am also happy that such scholars, intellectuals and great creators while having such opinions about me too, despite condemning (me) in the prefaces they write, are forced to give space to the short-stories of this good-for-nothing, which they publish in order to establish their authority in the market for stories.

Keeping aside the mass-produced volumes, victims of diabetic corpulence, written in the excitement of assault, thank God that this fakir never had this wishful thinking that he has done literature a great favour by writing just a few stories, publishing a weak and lean collection.

“I can humanize the Unseen but cannot unsee the human”

I am interested in history, but not the construction of history; and that too, frail and deadly construction of history? And that too in the field of fiction! I accept the taunt of being a lowbrow. I am not fond, too, of proving myself as the founder or framer, inventor or leader of any literary movement or method in that I run a campaign with the support of various means of communication. I do not have so much time. Those whose chest is narrow and back wide are welcome to their self-awarded honours and medals. I have no shame in admitting my secondary status in the arts (especially in fiction in that attacks from invaders are greater) so that all the others indeed keep proving themselves as being in the top rank – in fact, the very topmost artists. There should indeed be an artist of the second rank or a second-rate artist so that the existence of superiority be proven, and this crisis of artists (especially short-story writers) be at an end and they turn attention towards creative work with encouragement and focus, and maybe the whole matter may prove a success.

Various arts, be they fiction-writing or essay-writing, drama-writing or acting, painting or dance – all these for me are resources for comprehension of my own and others’ internal and external circumstance, to understand the earthly and cosmic relations of Man; and create space for having a dialogue with other humans. To attain an exalted status among them all or with anyone is not my issue and neither do I have any such pretensions.

I think fiction-writing is a difficult task; to write good fiction even more difficult. Great troubles have to be endured for it. Circumstance, experience, observation, study, perception, way of feeling and then the use of language. If the writer has capacity, they grant a wide perspective to everything. If the writer does not possess vision and is unable to use creative language in an effective manner for the expression of their vision, they give birth to an abnormal child who breathes for a little while then dies – to see whom people indeed come from afar; whose photos are indeed published in newspapers; who becomes famous indeed on radio and television; who becomes the cause indeed of scientific study and interest for some time; but eventually the jar of formalin is its fate. Or a mention in Ripley’s ‘Wonder Book’. There is no dearth of such wonders in the present age and when there is an abundance of wonders, they do not remain wonders.

The desire to have attention lavished towards oneself (by being published) is so strong and the inclination for attaining eternal fame without hard work, labour and study in our midst so much that it suggests a fake creative delirium. Circumstance, experience, observation, comprehension and way of feeling is often so incomplete, unfinished and limited that the glance neither comprehends nor reaches the outside the well. A passing acquaintance with a command over words, the arrangement of words, their meaningfulness and the structure of sentences leads to crafting fake prose. This is all due to intoxication with the passion for mass production and then the desire to be called ‘modern’ on top of that – so the story one seems like the story of another; as if all stories have emerged fashioned by the same pen. In these circumstances, one feels that if the short story has not already passed away by choking, it is definitely at its last gasps.

“I think fiction-writing is a difficult task; to write good fiction even more difficult. Great troubles have to be endured for it”

By all means, destroy the warp and weft of the short-story; do demolish the idea of time and space; even treat language with excess; smash the basic elements of the story (narration, circumstance, happening, etc) into pieces. But with reference to your masterpiece, at least do not let it be known as to why these extreme steps were needed after all. There is logic within creation itself, which brings together the validity for its existence. (To be continued)

This obituary was first published in The Friday Times.

Raza Naeem is a Lahore-based social scientist, book critic, award-winning translator, the recipient of a prestigious 2013-2014 Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship for his translation and interpretive work on Saadat Hasan Manto’s essays. His most recent work is a contribution to the edited volume ‘Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry’. He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association, Lahore chapter. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

Raza Naeem is a Lahore-based social scientist, book critic, award-winning translator, the recipient of a prestigious 2013-2014 Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship for his translation and interpretive work on Saadat Hasan Manto’s essays. His most recent work is a contribution to the edited volume ‘Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry’. He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association, Lahore chapter. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia