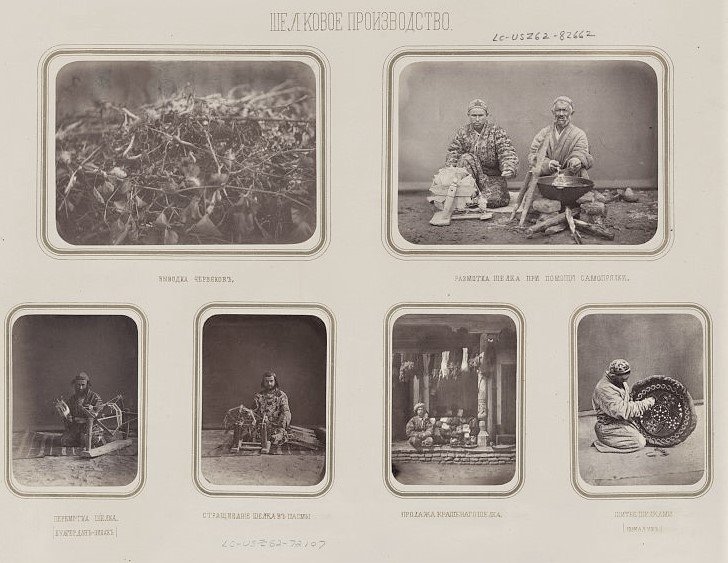

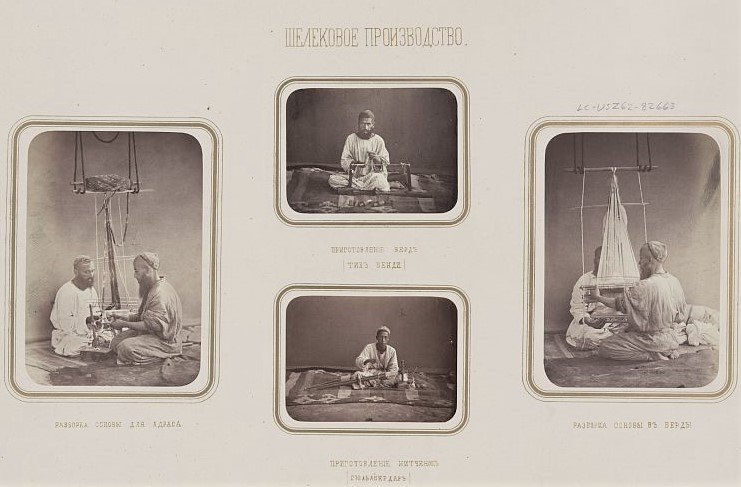

Central Asia is known for its long tradition of exquisite textile production. To this day, scarves or chapans woven using the ikat technique remain sought-after items for fashionistas around the world. Carpets are likewise a product of complex techniques that have been passed down for generations in the “rug belt.” Carol Bier, a historian of Islamic art, discusses in an interview with Elvira Aidarkhanova for Voices on Central Asia the cultural aspects of geometry in Islamic art, and the beauty of its form, pattern, and structure.

by Elvira Aidarkhanova

The history of geometry dates back to the early Arab world that later on spread to the Persian world and beyond (Central Asia, Spain, and North Africa where developed translations of, and commentary on, the ancient Greek texts about mathematics and philosophy, says Carol Bier, a historian of Islamic art who has published widely on cultural aspects of geometry in Islamic art that inform a beauty of form, pattern, and structure.

“I have studied a lot of geometry in Islamic art and architecture, an interest born of my earlier studies of textiles and textile patterns. The patterning in textiles is very much related to the technology of weaving or embroidery or resist-dyeing—ikat, or Abrband (from the Persian “abr”—a cloud, “band”—to tie), as it is called in Central Asia, at least in Uzbekistan,” says Ms Carol in an interview to Elvina Aidarkhanova, published in online research magazine Voice on Central Asia.

“So my interest in geometry and Islamic architecture and arts is very much tied to the relationship between craft and technology — building technologies in the case of architecture, says Ms Carol, concurrently, Research Associate at The Textile Museum in Washington, D.C., where she long served as Curator for Eastern Hemisphere Collections (1984-2001).

What my studies have revealed is the emergence in the Islamic World of an algorithmic aesthetic. So repetition itself has meaning, and that meaning, in my understanding, is very much tied to geometry, to making geometry manifest.

So my understanding and interpretation has taken several different directions, Ms Carol, who is currently a Research Scholar at the Center for Islamic Studies at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, CA, explains. One is the study of Qur’anic inscriptions on monuments that have geometric patterns.

I would argue that Qur’anic inscriptions, the passages selected for those monuments, may help inform us as to the meaning and the significance of the patterns as well as the buildings themselves. In particular, the word, Amthal, which is the plural of Mithāl, has many different meanings in relation to allegory, in relation to parable, but, for mathematicians, it means geometric problem.

According to the scholar, the Qur’anic passages can be interpreted in light of the geometric patterns on the buildings, such that the geometry is precisely making geometry manifest. That, in essence, is the interpretation that I have come to in my study of geometry, art, and architecture in the Islamic world.

Responding to a question, she says, “The spiritual meaning is not something that I have particularly explored. The primary ways to investigate this would be by looking at the textual tradition and, today, conducting interviews with practitioners—whereas I have for the most part worked with the primary sources (the materials themselves), so the material culture”.

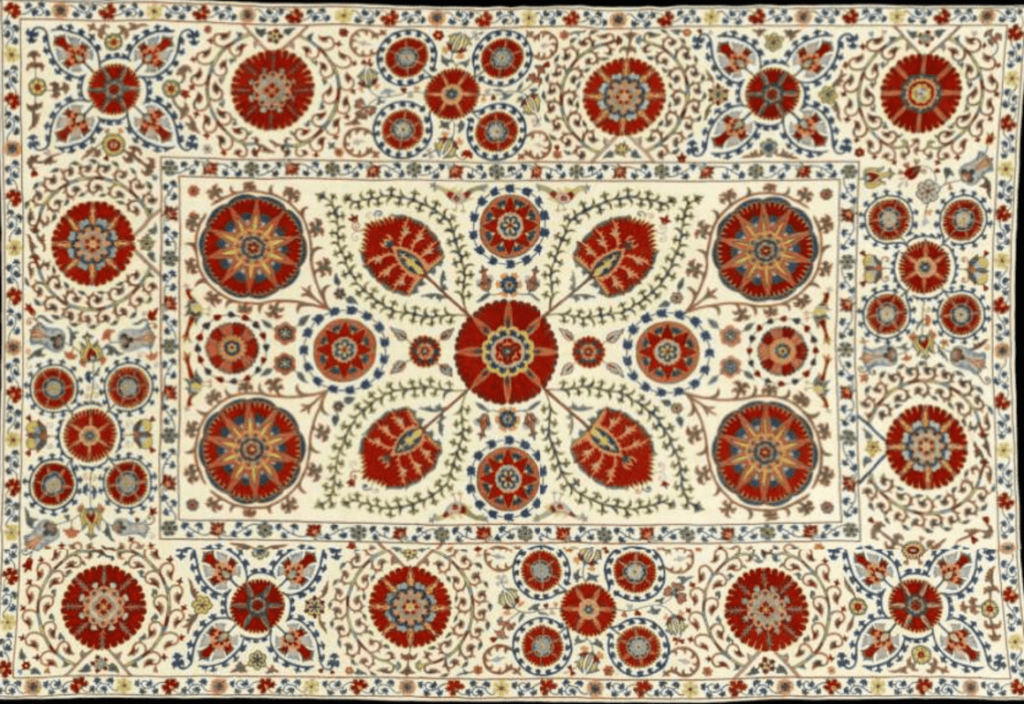

But what I can say is that all of the textile traditions — from felt-making (shyrdak) in Kyrgyzstan and embroidery (suzani) in Uzbekistan to carpet-making (qalin), rug products, and so forth — rely on renewable resources that are readily available in Central Asia. So there is a very long history, dating back to prehistoric times, of felt-making and textile manufacture.

The techniques for textile production in Central Asia are just absolutely extraordinary and many of them are still practiced today. There are very rich productions of ikat in, for example, the Fergana Valley. Ikat is a resist-dyed warp that is woven in Central Asia (and elsewhere).

“You have the cultivation of cotton, the procurement and preparation of the dye materials, the yarn preparation of the fabric itself, the dyeing and the weaving technologies. So a simple product like a scarf, for example, with its warp ends showing, is already the product of multiple technologies. In shyrdak/shyrdok, the cutting of the felt into two layers, and then placing one layer on top of the other, produces two identical patterns, but the colours are then reversed. So that’s a brilliant use of very simple technology, heat, and compression, to make felt from wool yarns and then play with the color and the ornament.

But there is symbolism — or symbols — in the designs, such as the horns of sheep, the beard of a goat, or elements of tools that are fundamental to society.

In Central Asia, there is also a sharp contrast between the herding cultures and the agricultural cultivators. There are nomadic populations, on the one hand, and settled populations, on the other hand. That contrast reflects the varied geography of the region, with desert areas, river valleys, and oasis towns.

About the textile arts of Bukhara, such as embroidery (suzani), pile carpet weaving, and ikat weaving, its relevance in today’s world, Ms Caril says, Ikat is called abr-bandi (tying of the clouds) and it has to do with the resist-dyeing of the warp yarns before weaving. And that is practiced very widely in the contemporary Fergana Valley, where multiple studios, ateliers, workshops, and factories produce what in English we have come to call ikat.

There is also a strong tradition of producing silk embroidery (suzani) in the areas around Bukhara, Samarkand, and Shakhrisabz, for example.

As far as I know, we can only trace ikat and suzani back to the 19th century, maybe the late 18th century, but we have earlier examples from elsewhere in the Islamic world. I am not sure how these technologies came to be transmitted to Uzbekistan, but they were definitely present by the nineteenth century and are very strong today, as ms Carol put it.

Madina Kasimbaeva in Tashkent is a contemporary suzani embroiderer. Her contemporary embroidery in a historical idiom has been very well recognized internationally. Within Uzbekistan, she has received one of the presidential awards for artists; her work is also exhibited in the British Museum in London.

Read more: How Ikat Accompanied History in Central Asia

Responding to the question about her research on the Kyrgyz kurak korpe, also common in Kazakhs and the origin of such terminological similarities in Central Asian countries, Ms Carol says ‘Yastık‘ is the word used for a pillow in Turkey, as far as I know, and all of those words are closely related.

“You also find that sharing of vocabulary in other contexts—from Persian to Turkish, Turkish to Persian, or Tajik to Turkic languages. Many of the words are the same. So ‘zhastyk,’ ‘ýassyk’, ‘zazdyk,’ and ‘yastık’ are all related (with a few dialectical differences), and there are also similarities between the arts they use.

Such cultural similarities can be seen in techniques for producing textiles, architecture, and food, she argued.

That being said, the ornaments depend on which type of culture people these countries belong to. For example, some Central Asian ornaments are much more of an urban product; others are a nomadic product. Different designs are chosen and repeated to make patterns among settled urban populations that are selected among nomadic populations.

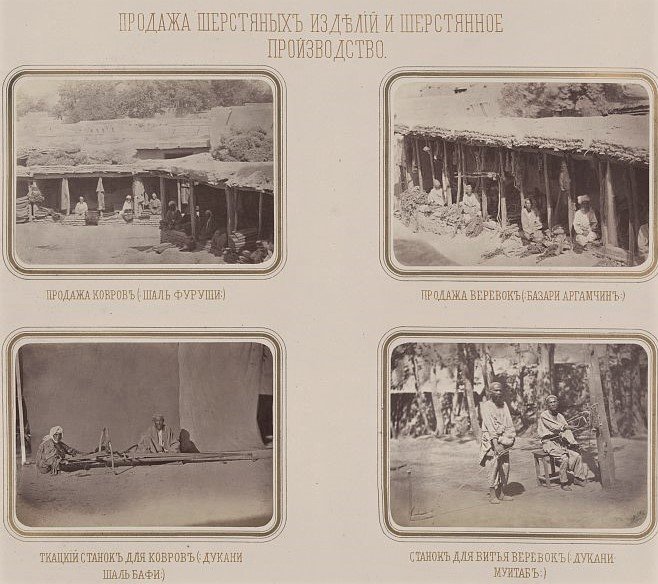

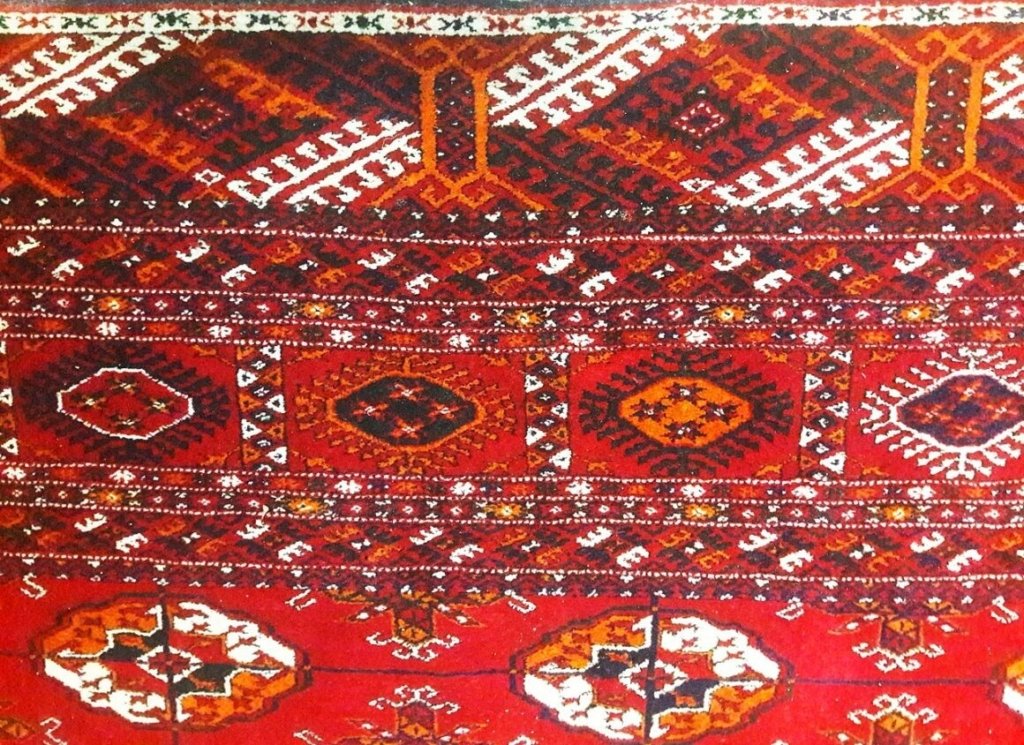

The premier product of nomadic culture, of course, is carpets. You see them used not only on the floor, as we do in the West, but also as doors and covers, for example, to cover trunks or as furnishings, as well as to cover the floor of a tent (yurt) structure. Pile carpets may have wool warp, wool weft, and wool pile—it is the pile in the carpet that features patterns and designs.

About patchwork traditions and Oriental carpets, and their origin, Ms Carol says patchwork is a very important domestic technique—it is something that is done in people’s homes rather than in factories. Scraps of older textiles are put together to make quilts, covers or horse covers, or horse head ornaments.

“I have studied much more about carpets than about patchwork. Starting with the terminology of “Oriental carpets” is already an indication of an outsider’s perspective. To call something oriental is to suggest that it comes from the Orient, which in the nineteenth century—to which the history of European collecting of carpets dates—was anywhere east of Istanbul. It was not the Far East as we think of it today.”

The very fact of phenomenon of “oriental carpets” demonstrates that these textiles transcended their cultural origins in the “rug belt,” which extends across Central Asia to include Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, part of Egypt, North Africa, and Spain. This region is arid (with dry/low rainfall), making cultivation problematic, so sheep husbandry and herding provide people’s primary economic livelihood. Wool, of course, is a renewable resource: you shear the sheep once or twice a year and then the wool grows back. It is not like shish kebab (in Turkish ṣiṣ kebab), which is not renewable.

The carpets produced in these areas became favorite products traded or gifted to the colonial powers of Europe. Thus, carpets transcended the Eastern world and became a feature of the Western world — which gave rise to their being called ‘Oriental carpets’ as a category. For the most part, that category still holds, although it is considered politically incorrect today to refer to them as such. But no one ever wove an ‘Oriental’ carpet. A woman would simply weave a carpet. That is what it would be called in her own culture.

As for patchwork, it is less a commercial product and more a domestic product often made from scraps of older textiles. One of the thoughts is that the arrangement of those little squares of fabric may ward off evil. So it has a protective quality for those who use it or wear it, Ms Carol says.

Historically, it was predominantly women who used to do this type of work, she argues. I think men tended to be responsible for the herding of the animals, the maintenance of the herd, and animal husbandry. Meanwhile, the women tended to be in charge of milking the animals and making milk products, as well as the craft traditions of yarn preparation and weaving.

“I have seen men involved in felt-making—it is traditionally a male-dominated field because it takes a lot of stamping and pressure to turn the wool into felt. Felt was typically used to make shepherd’s coats, felt floor coverings, or dervish hats. As for embroidery, that is also — in the domestic context — a women’s realm. In the commercial context, I have seen men involved in embroidery in northern India, Western China, and Central Asia. But there are, within these different textile technologies, certainly gender roles and gender differentiation.”

In response to a question about carpet weaving, the scholar says it has a much longer history than the Islamic world, which in Central Asia dates back to the 18th century.

The oldest carpet we know of comes from a kurgan (barrow) grave in Siberia in Russia. It is called the Pazyryk carpet from the Pazyryk Kurgan. It was discovered in 1949 in the permafrost of Siberia. Based on its style, it dates back to the fifth or fourth century BCE — a time before Alexander the Great. What is interesting about it from my perspective is that it has extraordinary technical properties. It is an example of the advanced technology of weaving, and yet we do not have any knowledge of how it came to be. So it has very tightly spun yarn, plied yarn—beautifully knotted. The pattern is already laid out like much later oriental carpets, with a square or rectangular field, repetition of a design, and multiple borders surrounding the central field, she explains.

Read more: The Treasures of Pazyryk Kurgans in the Hermitage Museum

Thus, carpet weaving dates back to at least the fifth or fourth century BCE. We have fragments of carpets from a thousand years later, in the Seljuk era, and then we have entire carpets from the fifteenth century and more recently.

In the Soviet era, during the period of collectivization, factories were established for the weaving of carpets, and so the tradition continued, but more in a commercial environment than in a domestic or nomadic one.

Answering a question about the influence of trade and commercialism on the development of these textiles, Ms Carol says there is both the domestic tradition — where textiles were made for home use and for use by local populations — and commercial production.

Tribal materials were also sold when money was needed; they became a commodity for monetary exchange. The most significant collecting efforts occurred during the Russian Empire. The greatest museum collections in the world thus became those in St. Petersburg and then, in the Soviet period, in Moscow.

The ethnographic museums in those cities have some of the finest holdings of Uzbek carpets. Their bright colors are still fresh today if they have not been exposed to too much light or too much washing. They are really beautiful.

In response to a question about her interests in the subject, Ms Carol says one aspect that I personally love studying is beauty — the pattern, shape, design, colour… and then, as I mentioned earlier, I am fascinated by the interrelationships of craft and technology, craft production, and the manufacture of products, whether for home use or for commercial use. I can extend that further and say that I am fascinated by the interrelationships of design – structure – technology – and function.

As I have mentioned some of those connections, whether it is the resist-dyeing of the warp, and then the weaving, and then the manufacture of scarfs; or the animal husbandry and the yarn preparation and the dyeing and the weaving of carpets and the different methods of making patterns. The warp resist is one, and that is what gives the ikat pattern all this variation of up and down within the design motifs. But in carpets, patterns are formed by individual knotting of segments of yarn one by one in sequence. So it is a fascinating subject to study. — Courtesy: Voices on Central Asia

Elvira Aidarkhanova is an independent expert on Central Asia and an analyst. She has done PhD in International Affairs.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia