By Ghulam Amin Beg

On Tuesday, September 14, 2010, I had written this article and published on the Simurgh Institute blog, which received several comments and further elaborations. The article analyzed the opinion post by Selig S. Harrison published in the New York Times in August the same year under the title, ‘China’s Discreet Hold on Pakistan’s Northern Borderlands’.

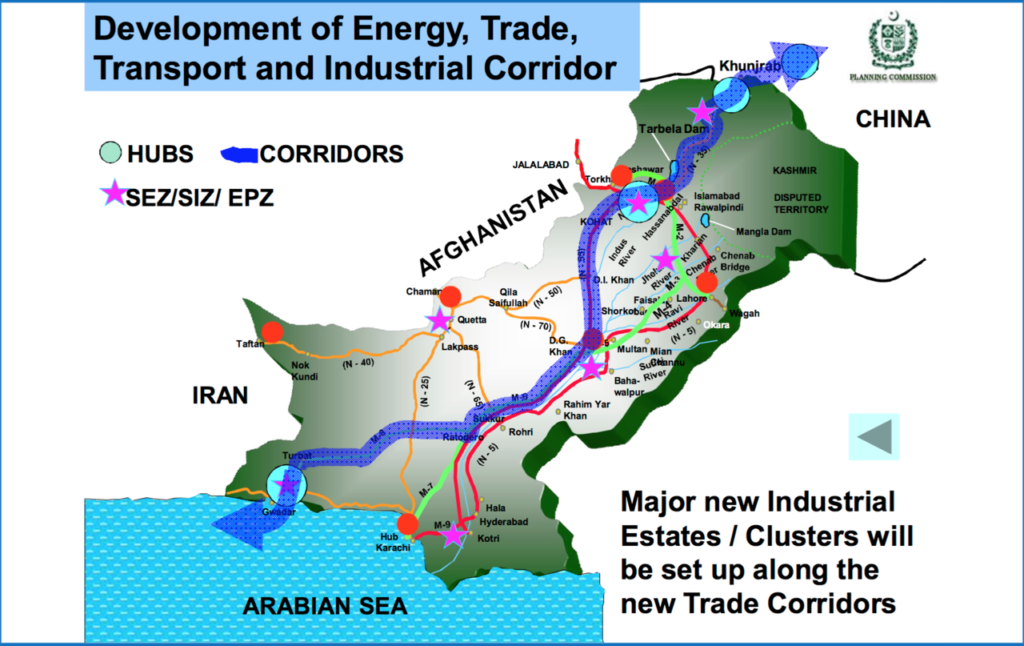

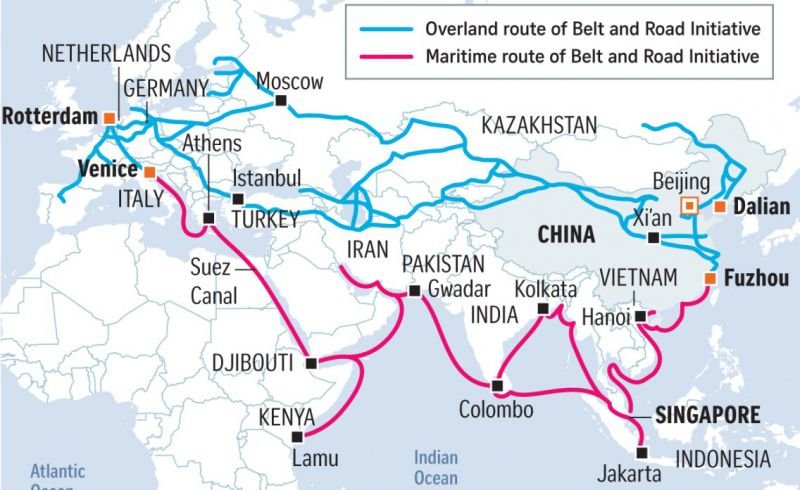

Today, September 20, 2019, it’s almost a decade now. Much water has flown under the bridge since then and many of the assertions of Harrison has proved wrong, but the very rationale for his writing: Chinese ambitions and the US and India aiming to contain it continues to be relevant. When elephants fight or make merry, it is the grass that suffers, as was quoted a leading African leader of the Non-Aligned Movement during Cold War. I have updated it, as many things happened down the road. We have seen the evolution and launch of China’s $3 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), dubbed as “21st century Silk Road”, the operationalization of the $60 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), and reports of the fire and fury of Washington exerting pressures on economically and politically fragile governments especially the current one in Islamabad at different levels to roll back or slow down CPEC.

Meanwhile, Modi’s Hindutva nationalistic fervor continues conspiring with Tel Aviv and its sponsors to dissect and disconnect Pakistan’s strategic links with China, changing status quo in Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh and now openly craving and woofing to retrieve Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan (GB).

New Great Game

New Great Game

Some analysts rightly argue that the term ‘new great game’ is a misnomer and that the new world order is multipolar and there are many players playing their own games. So it is not a one grand design between two powers, but multiple powers — big and small — and multinational corporations (MNCs) competing for economic, political and security interests under the neoliberal neocolonial agenda. Neither Pakistan, nor Afghanistan or the Central Asian states are pawns. Even smaller territories and regions within these state systems are not mere spectators. While China is a big country with a huge economy, US has historically replaced the British in this region and India has economic and political ambitions, it must be noted that over the years Russia has regained influence as an international player and is a power broker in Central Asia. Both China and Russia have provided a framework under the Shanghai Cooperation Organization(SCO) for peace, cooperation and security in the region. All the potential flashpoints — Afghanistan, Kashmir, Xinjiang, the Farghana valley — are ring-fenced as potential areas of opportunities to promote cooperation by creating local opportunities. China has invested a lot in western regions and created trade and infrastructure links across all the borders of Xinjiang, including, of course, the CPEC through GB to Gawadar.

The article started with this question: “Is Gilgit-Baltistan a new pot for cooking a mix of Chinese, South Asian and continental cuisines by the Yankee and the Asian dragon with hot spices from the South Asian vultures? Or is Gilgit-Baltistan coincidentally wedged between the devil and the hard rock or is it only a corridor for the exchange of flood waves?”

Nine years on today, it seems, at least in the eyes of Indian think tanks and policymakers after the changed status quo in Kashmir, and for the Chinese since they have signed border agreement with Pakistan in the 60s, GB is an important strategic economic corridor, which links energy-starved South Asia with energy-rich Central Asia. However, for Islamabad, the Pakistani think tanks and media, GB is only seen through the prism of a narrow security paradigm, attached to the old status quo on Kashmir and its geostrategic importance of linking with China for military and security cooperation. For Pakistani think tanks, perhaps, access to energy resources of Central Asia is best served through Afghanistan and tribal areas once peace is restored the violence-hit region.

Festering wounds

I also referred to the old or the first great game which was played by the British Empire and Tsarist Russia ending in the division of Badakhshan in Central Asia along the Panj River into what is now known as Afghan Badakhshan and Tajik Gorno-Badakhshan. Later, when the sun set on the British empire in the South Asian Subcontinent, as we now find through published reports and diaries, that with full knowledge of the British colonial officers who were still in charge of the security forces on both sides, they deliberately left Jammu and Kashmir, Ladakh and Gilgit-Baltistan disputed and as an open wound for their own interests, which continues to bleed. This colonial crime led to three wars and many proxy wars between India and Pakistan and with real risks of nuclear escalations and threatening regional peace and security.

Similarly, at the height of the Cold War, when the former Soviet Union entered Afghanistan and the US and allies fought back through proxies and denied the polar bear access to the warm waters, it ended in a devastated Afghanistan, human catastrophes and ethnic scars continue to bleed.

What will happen this time, when the uneasy, but rising red dragon meets the naked American imperialism at its very borders in Central Asia for the first time, and when New Delhi darbar’s greater ambitions and Pakistan’s sense of state insecurity — and notions of strategic depth — and internal anomalies of misgovernance oscillate courting between the two poles? While Tehran continues to pinch the US-Israeli-Saudi nexus in the Gulf, and Iraq, Yemen and Syria being the new battleground for a new game, what new order is in the making in this region? Would the US and Indian nexus allow a new axis between China, Pakistan, Russia, Iran and Turkey for domination in Central Asia and the Middle East? How important is the land route and corridor passing through Gilgit-Baltistan in this new great game? What scenario and outcomes are predictable and what are the risks and threat to be mitigated by Pakistan and China vis-à-vis Gilgit Baltistan?

On August 26, 2010, Selig S. Harrison, director of the Asia Program at the Center for International Policy and a former South Asia bureau chief of The Washington Post published an opinion in the New York Times entitled as, “China’s Discreet Hold on Pakistan’s Northern Borderlands”.

Building his arguments around the increasing Chinese strategic investments in Pakistan in terms of providing men, money and machine, especially in building the Gwadar Port (which the author called Chinese-built Pakistani naval bases in Gwadar, Pasni, and Ormara), widening of the Karakoram Highway and projects related to construction of small and large dams and ‘construction of 22 tunnels in secret locations’ in the Karakoram and Himalayas, the author had termed it as, ‘influx of an estimated 7,000 to 11,000 soldiers of the Peoples Liberation Army (PLA). Most of this has now proved wrong and misinformation.

In this file photo taken on September 29, 2015, commuters wait to travel through a newly-built tunnel in Gojal Valley. Photo: AFP

In this file photo taken on September 29, 2015, commuters wait to travel through a newly-built tunnel in Gojal Valley. Photo: AFP

Why China would take this gigantic step? In the author’s own analysis, because, “China wants a grip on the region to assure unfettered road and rail access to the Gulf through Pakistan as it takes 16 to 25 days for Chinese oil tankers to reach the Gulf. When high-speed rail and road links through Gilgit and Baltistan are completed, China will be able to transport cargo from Eastern China to the new Chinese-built Pakistani naval bases at Gwadar, Pasni, and Ormara, just east of the Gulf, within 48 hours”.

What Harrison suggested to stop China to ‘engulf’ Gilgit-Baltistan and the next steps for America are:

“The United States is uniquely situated to play a moderating role in Kashmir, given its growing economic and military ties with India and Pakistan’s aid dependence on Washington. Such a role should be limited to quiet diplomacy. Washington should press New Delhi to resume autonomy negotiations with Kashmiri separatists. Success would put pressure on Islamabad for comparable concessions in Free Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. In Pakistan, Washington should focus on getting Islamabad to stop aiding the insurgency in the Kashmir Valley and to give New Delhi a formal commitment that it will not annex Gilgit and Baltistan. Precisely, because the Gilgit-Baltistan region is so important to China, the US, India and Pakistan should work together to make sure that it is not overwhelmed, like Tibet, by the Chinese behemoth”. (To be continued)

![]() Ghulam Amin Beg, is an international affairs commentator, development practitioner, policy advisor on youth, civil society and local governance with an eye on mountain areas in Pakistan and Central Asian region.

Ghulam Amin Beg, is an international affairs commentator, development practitioner, policy advisor on youth, civil society and local governance with an eye on mountain areas in Pakistan and Central Asian region.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia