Laila Haidari risks her life to run the country’s only private rehabilitation centre, helping hundreds of addicts a year

Kabul

People shelter under the Pul-e Sokhta bridge in western Kabul, during a police round-up of suspected drug addicts. Photograph: Ahmad Masood/Reuters

Laila Haidari is considered a criminal, despite never committing a crime. The 40-year-old works with drug addicts in Kabul. “The addicts I work with are considered criminal and dangerous and by extension I am considered criminal,” she says.

Despite opposition and death threats, eight years ago, Haidari opened the city’s only private drug rehabilitation centre, which so far has helped nearly 4,800 Afghans who would otherwise have ended up on the streets, or worse, dead.

She opened the centre, called the Mother Camp, after watching her brother fall into addiction. “I cared for my brother and helped him recover, even if it was briefly, because I believe that he deserved to be saved. He was a good man,” she says. Each of the addicts who pass through her shelter are good people who’ve gone astray, she adds, and they deserve a second chance.

Afghanistan’s drug problem is not a secret. The country is the world’s largest producer of opium. In November 2017, the UN reported that opium production had increased by 87% over the previous 12 months to a record high, despite almost two decades of counter efforts by the US.

According to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (Sigar), since 2001 the US has spent $8.6bn on disrupting the illicit drugs trade, yet the country still produces about 80% of the world’s opium.

Afghans remain among the worst victims of the failed war on drugs. According to the 2015 Afghanistan national drug use survey, in a country of 35 million people, an estimated 2.9 million are addicts. But there aren’t enough government-run shelters to meet the growing needs. Kabul has 27 government shelters and there are about 115 across Afghanistan – all of which are over capacity.

Mother Camp, named by the first drug addicts Haidari took in, was established in 2010. “I used to look after them, clean them, cook for them and sometimes even feed the weaker ones. That is when they started to call me ‘mother’,” she explains.

Using her own savings, Haidari, once an aspiring filmmaker, rented a small space in the west of Kabul to open the shelter. It was basic, with furniture donated by friends and family.

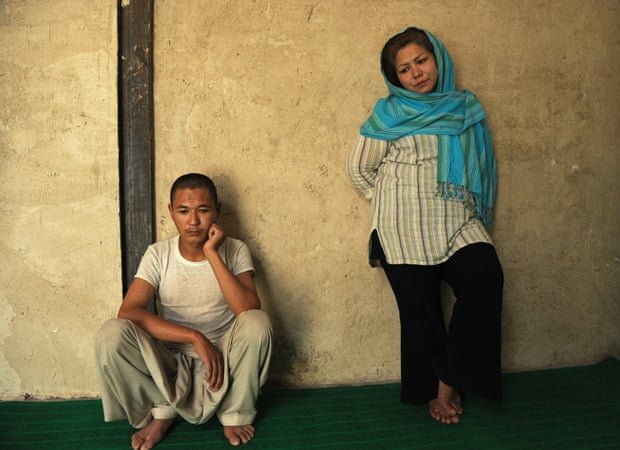

This year alone the shelter has admitted 117 new addicts, most of whom were rescued from under Kabul’s Pul-e-Sokhta bridge, known for the homeless community that lives there. The shelter has a capacity of 25 residents at one time, but it has hosted up to 40. Haidari and her team try to keep track of residents after they leave, but since many of them are homeless it’s not easy. About 20% of people who leave the centre will drop off the radar, while some will have relapses and return. So far this year, everyone who’s been in the shelter is accounted for and in various stages of recovery.

“The addicts normally stay 30 to 40 days at the camp. Once they are admitted to the shelter, volunteers clean, shave and wash them, explains Jalil Pažwak, a young Afghan media professional, who volunteers at Mother Trust, the NGO that runs Mother Camp. The shelter takes the “cold turkey” approach to recovery – a common approach in the country, where resources and access to other medication and expertise is limited. Doctors are on hand if any problems occur. “Cutting them off completely from drugs is the main step and the important one. In our experience it has never had a negative effect. But it helps them become determined in their mission of getting rid of addiction,” Haidari believes.

Residents are encouraged to join in group counselling and attend meetings, and eventually help with cooking and cleaning.

It costs between $1,500 and $3,000 every month to run the shelter, depending on how many residents it hosts. The costs are met by Haidari and friends and family. She’s yet to receive any money from government or international organisations.

In Afghanistan, drug addicts are seen as unwanted and a nuisance. “Contributing funds to help addicts has never been met with much enthusiasm among Afghans.

“The initial years were the most difficult and I put all my savings and money to this project,” she says.

To help meet costs, in 2011 Haidari opened a restaurant – the Taj Begum, which means “the crown of a queen” – run by the residents and furnished with donations.

There were worries that no one would visit a restaurant operated by recovering addicts. “However, we were able to generate interests among a lot of people, especially those already familiar with our work. The clientele is largely young, educated Afghans who are eager to support our work,” says Haidari. Taj Begum serves Afghan cuisine, tea and snacks.

However, this venture has not been without trouble. Men and women can socialise freely, which has ruffled feathers in a conservative society. “They’ve accused me of encouraging immoral and unIslamic values. Some have even accused me of running a brothel,” she says. She has received death threats.

But, Haidari has her supporters. Mina Sharifi, founder and director of Sisters4Sisters, a mentorship programme for Afghan girls, says she is doing important work. “We’re so far behind in even understanding what addiction is, never mind accepting it as a disease to be treated. If we wait for society and the government to catch up, that’s an immeasurable loss of valuable lives,” she says.

“Laila has combined addressing drug addiction with being a female lead in the fight. These are two huge things that many people here have a problem with. Her critics are scared of change and intimidated by what her success, with almost no money, says about their progress,” Sharifi adds.

Her work has received international attention. A documentary of her life and work – Laila At The Bridge – recently premiered in North America and at several European film festivals.

Despite constant threats to her own life and safety, Haidari remains determined to continue. “It has it’s flaws, but this is a good country, with good people who are thirsty for compassion. They deserve to be saved.”

The feature was first published in The Guardian, UK on January 3, 2019

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia