“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.” Arundhati Roy, Financial Times, April 3, 2020

by Nazish Afraz

The COVID-19 crisis is leaving even the most advanced economies of the world reeling, testing the limits of cooperation between nations. The European Union, despite coming together to procure equipment jointly, share medical resources, finance research and support SMEs and workers, has come under criticism for not doing enough. Germany, for example, is being criticised for not offering adequate assistance to other overwhelmed European states and for rejecting a plea to share debt in the form of Eurobonds. ASEAN too has struggled to come up with a solid joint response other than issuing statements of solidarity.

In this context, while it was refreshing to see South Asia break the hiatus of five years and come together under SAARC to try to coordinate responses to COVID 19 and share resources, it was too little, too late. Even at a time when they are both on the same side, trying to battle a common enemy, Pakistan and India are not being able to collaborate with each other. As both nations reflect on national priorities while dealing with the crisis, it is a good time to take stock of the costs of such non-cooperative relationships, and the possibilities available for a less hostile, and more prosperous and stable future.

South Asia: poor populations living in an uncooperative neighbourhood

Regional exchange of goods and services, people and investment, and cooperation in critical areas of energy, environment, water, health and infrastructure in South Asia is currently minimal. The Asian Development Bank’s Asian Regional Cooperation and Integration Index, a composite index consisting of 26 indicators across six dimensions: trade and investment; money and finance; regional value chains; infrastructure and connectivity; the movement of people; and institutional and social integration, ranks South Asia second from the bottom in Asia on regional cooperation and integration.

Yet South Asian economic history stands testament to the correlation between trade and prosperity. The region has flourished in the times when its location has been leveraged for trade, for example during the Indus Valley civilization period (3300-1300 BC), the Mauryan Empire (600-300 BC), and the Mughal era (1526-1720). Conversely, as exemplified by the current moment in history, disconnected regional trade and poverty have also gone hand in hand.

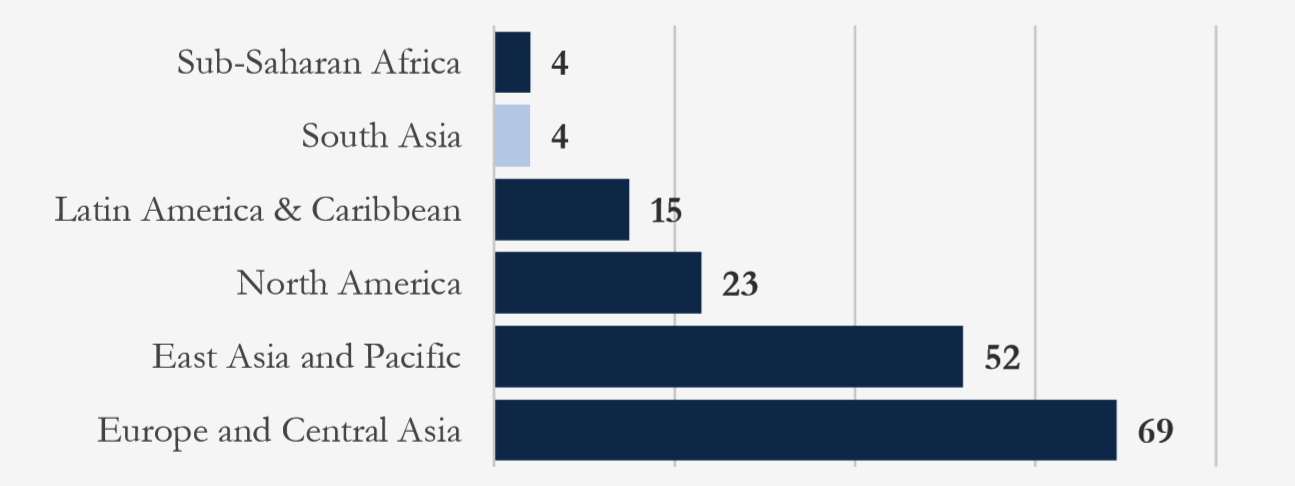

The extent of the disconnection is stark: intra-regional trade in South Asia is just four per cent of its trade with the world. In contrast, intra-regional trade in Europe and Central Asia is 69 per cent, and in East Asia and the Pacific is over 50 per cent (Table 1). And while other more functional Asian trading blocs have expanded their intra-regional trade over time, South Asia has stagnated at the same low figures for decades.

Figure 1 Intra-regional trade, per cent of trade with the world, 2018

This outcome is not due to lack of trade potential between neighbours. Trade within South Asia has the potential to increase three-fold, from $23 billion to $67 billion (Kathuria 2018). Trade between the two largest economies in the region, India and Pakistan, has the potential to increase 27 times. Their size, geographic distance, common border, common language and culture, and common colonial history make them ideal trade partners. Pakistan’s exports to India, for example, could grow 45 times, and in fact, these potential exports are over 3 times larger than Pakistan’s potential exports to China (Afraz et al 2019). Accompanying these potential expansions in trade are positive impacts on the balance of payments and consumer welfare. Savings on aggregate consumer expenditure from using less expensive imports from within the region alone are estimated to be to the tune of USD 2 billion, representing a saving of 31 per cent on the import bills in these product categories in South Asia (Chatterjee and George 2012).

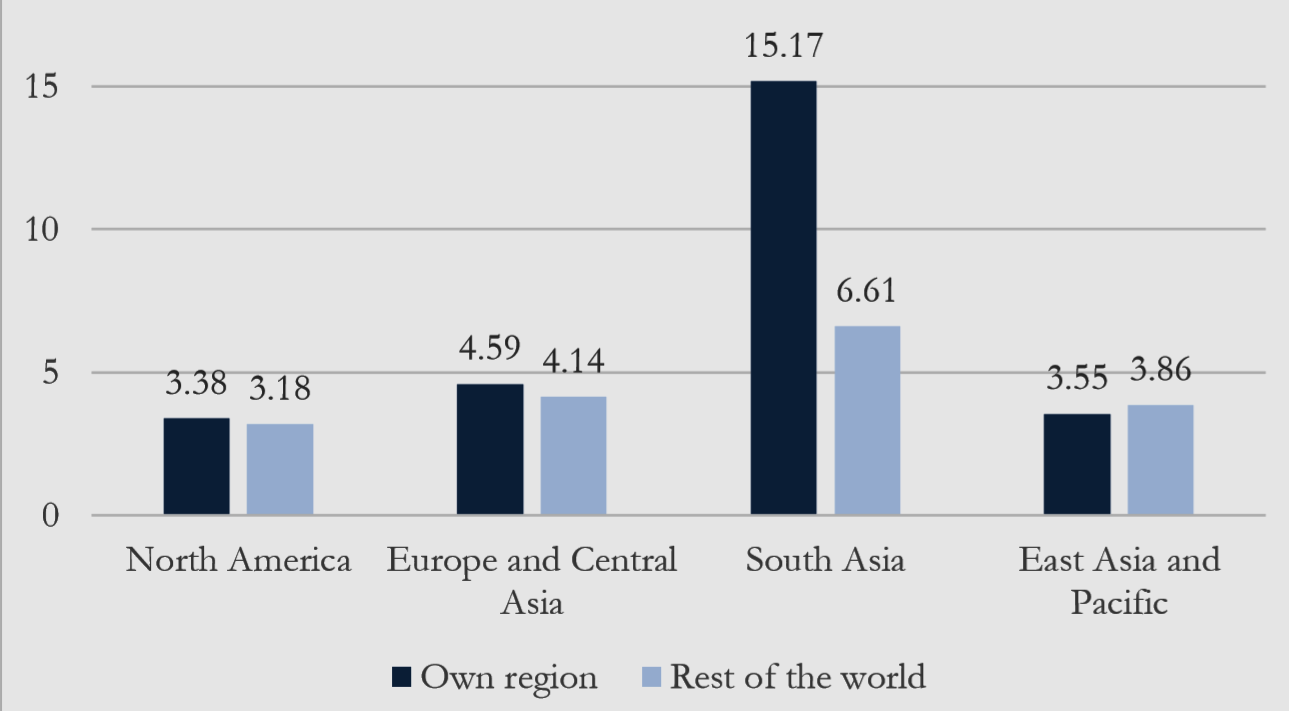

A host of deliberate barriers hold the region back from reaching this potential. Tariff rates are set such that it is much more expensive to trade with each other than it is to trade with countries that are much further out (Figure 2), and numerous studies have documented non-tariff barriers (such as quotas, sanctions, standards and administrative compliances, lack of land trading routes and banking channels) and connectivity costs. The low people-to-people contact also means that trust deficits and misinformation about perceived trade barriers also persist, contributing further to the low trade (Kathuria 2018, Taneja 2007, Afraz and Khawar 2019).

Figure 2 MFN weighted average tariff rate, Per cent

As with trade, potential gains to cooperation in water, energy and climate change are also well documented. On energy, electricity supply and demand patterns in South Asian nations are generally complementary. For example, the hydropower producing wet seasons in Bhutan and Nepal coincide with peak summer electricity demand in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, creating opportunities to trade. Yet less than 20 per cent of the region’s hydropower potential is utilized, and the region continues to depend instead on imported oil and coal for energy generation. In addition to the reduced availability of electricity, this puts pressure on both balances of payments and erodes air quality. South Asia was reported to have more frequent power outages than any other region of the world in 2011-2015, and the second-largest population living off the grid, impacting both households and businesses, for whom energy availability is a critical bottleneck. For water too, rapidly plunging water tables make it imperative to cooperate for water management not just for prosperity, but for basic survival.

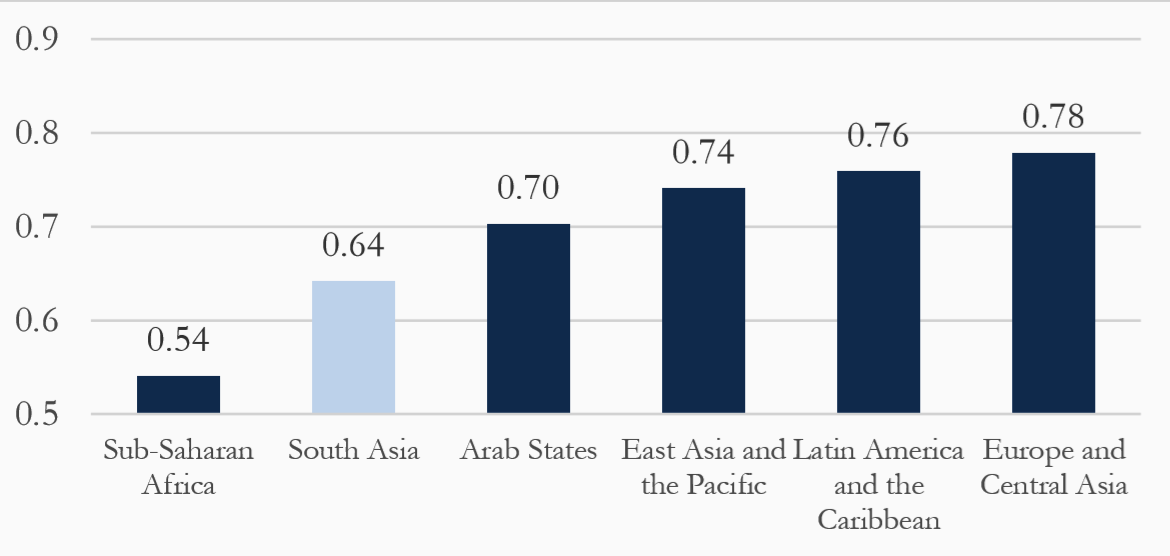

Accompanying the low regional cooperation and integration, are low levels of prosperity and poor human development outcomes in the region – second only to Sub-Saharan Africa on every count of deprivation. South Asian children can expect to complete 1.4 fewer years of education and live 5.4 fewer years as compared to East Asian children. 11.3 per cent of the South Asian population lives in severe multidimensional poverty, compared to 1 per cent in East Asia (UNDP Human Development Report 2019).

Figure 3 Human Development Index, 2019

In this scenario of low prosperity, realizing the potential for regional trade and regional value chains, tapping into regional energy markets, and coordinating to share experiences and data to manage climate change and natural disasters can provide a much-valued vent for growth. Yet, these potential opportunities are missed. The region has seen growth being held hostage to politics, decade after decade.

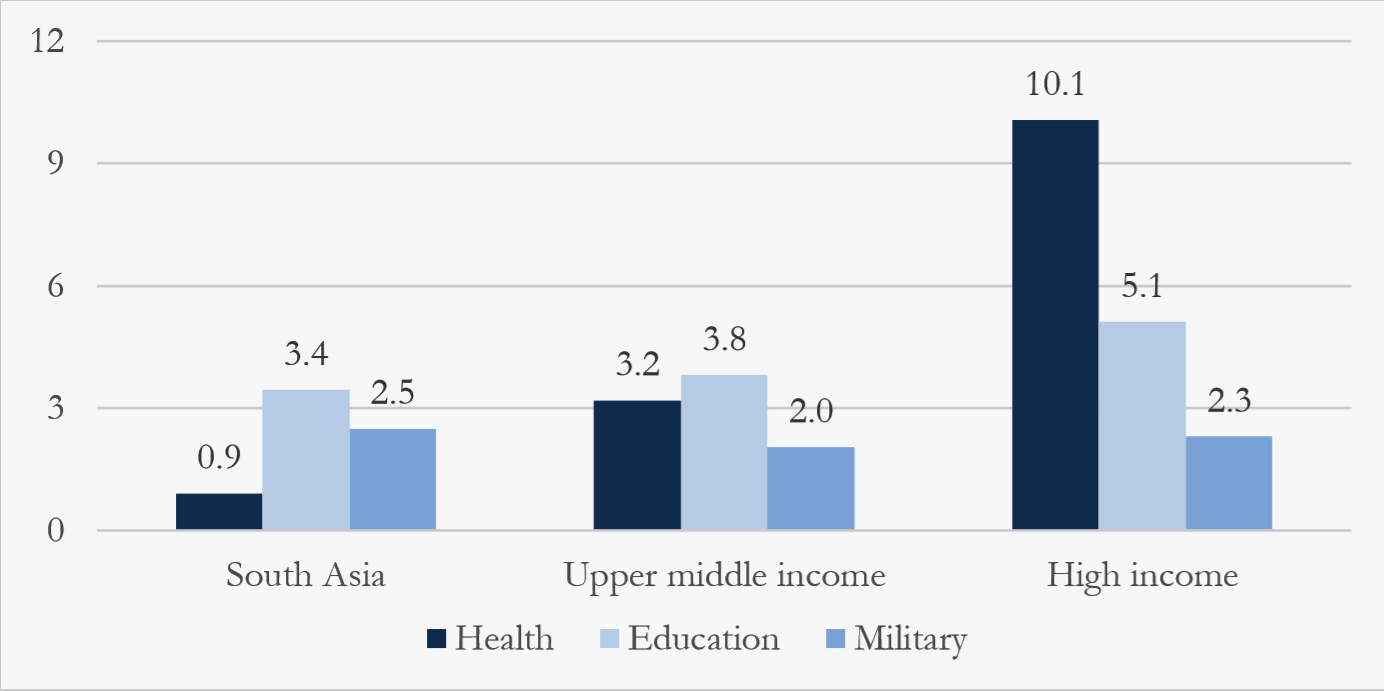

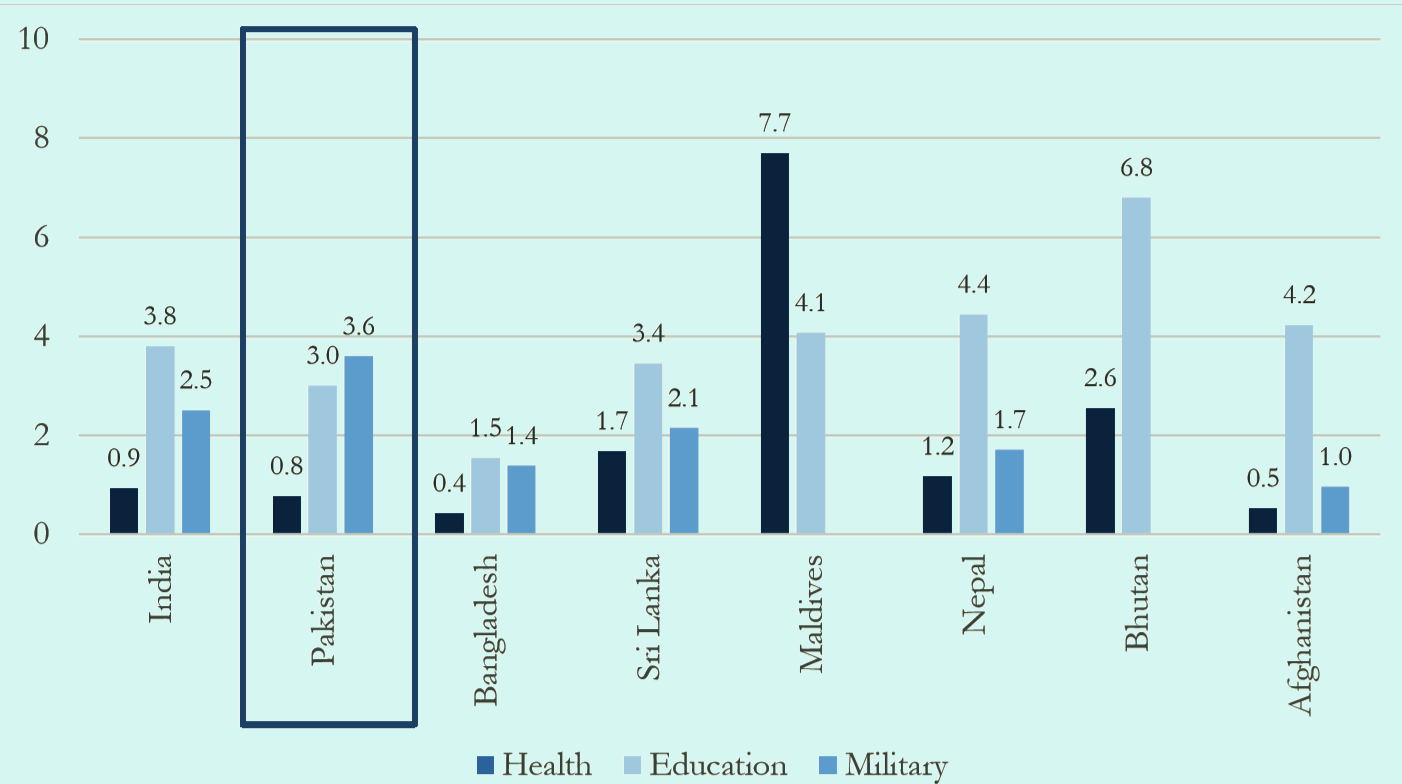

The uncooperative mindset vis-à-vis regional neighbours also distort spending priorities of limited budgets, requiring expenditures to be actively diverted to defence. As shown in Figure 4, South Asia as a whole spends more of its GDP on military expenditure than on health compared to higher-income economies. It is evident that countries that have achieved higher levels of income have allocated greater proportions of their income to education and health relative to their military.

Figure 4

Note: Data is for 2016, the last year that consistent figures are available for the three-country groups

This is true particularly for Pakistan, which, as shown in Figure 5, devotes 3.6 per cent of GDP to military expenditure, the highest in the region. India, the second-highest, spends 2.5 per cent.

Figure 5 Military vs. human development expenditure in South Asia, 2016

Note: Data are for 2016, the last year that consistent figures are available for most South Asian countries, apart from education data for India (2013) and military expenditure data for Maldives and Bhutan (not available).

The ongoing health pandemic lays bare the impacts of all these years of underinvestment in healthcare for countries like Pakistan, which had government hospitals overflowing beyond capacity even before the surge in demand ascribable to COVID 19. Ali (2013) notes, moreover, that “the greatest loss of human life and economic damage suffered by South Asia since 2001 has not been due to terrorism and its ensuring conflicts, but rather due to natural disasters ranging from the 2005 Kashmir earthquake and the Indus flood of 2010 to the seasonal water shortages and drought”. These disasters need an army – not of armed soldiers though, but of healthcare professionals.

Added to this, the demographic bulge brings in 1.5 million new young people for Pakistan to find jobs for every year. These could be a boon if it were not for the year after year of underinvestment in education. The World Bank’s human capital index paints an alarming picture: Pakistani children achieve, on average, less than 40 per cent of their productivity potential for lack of complete education and full health. Low labour productivity contributes to low competitiveness, which has to be contextualized in Pakistan’s recurring balance of payments crises that land Pakistan at IMF’s door every few years, handing over the reins of the economy in every electoral cycle. Equipping these young people with the education and skills they need to get high productivity jobs needs another army – again not of armed soldiers, but of education professionals.

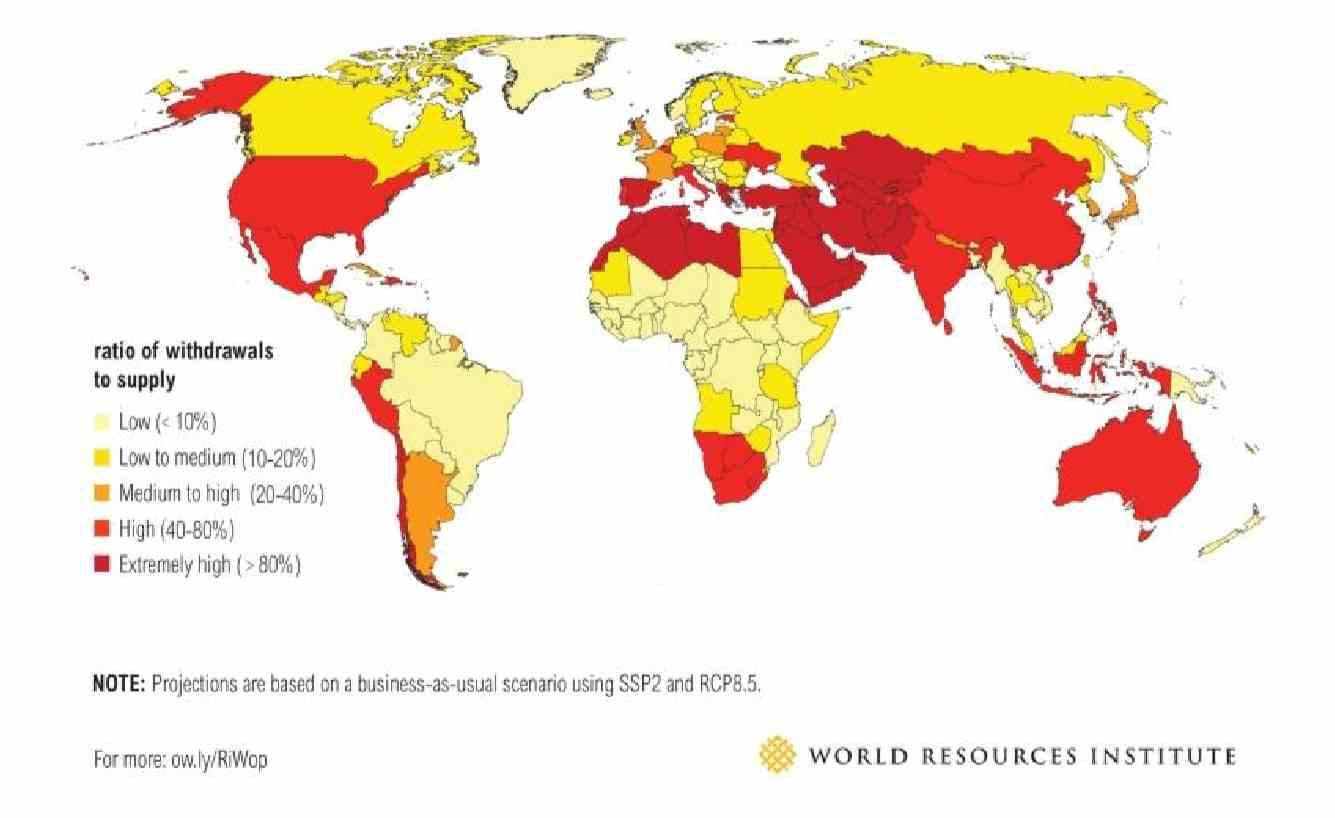

It is not just human development, but also climate change that necessitates a rethink. To pick an example, water tables in Pakistan are declining rapidly. According to the World Resources Institute, Pakistan is ranked twenty-third amongst countries most likely to become water-stressed countries by 2040. The Indus Basin Aquifer, on which the country is dependent, is the second most overstressed groundwater basin in the world (Richley et al 2015). Excessive silt deposits have reduced the storage capacity of both Tarbela and Mangla, Pakistan’s largest dams. Added to that, two-thirds of the Himalayan glaciers will have melted by the end of the century if emissions are not reduced. Even with reduced emissions, the number remains one-third, causing rivers to start drying up for parts of the year as early as 2050. This has repercussions not just on food availability but also on energy generation. Further south, the rise in sea levels is expected to increase the intrusion of seawater into the delta, and into coastal groundwater (Johnson 2019, Young et al 2019).

Even before the COVID-19 crisis then, it was becoming increasingly clear that a strategy of regional hostility was not sustainable for Pakistan, or for the region as a whole. The current status of the economy, the balance of payments, human development and climate change have created the perfect storm. The coronavirus ravaging country after country is a reminder to rethink priorities, a reminder also that while geographical borders demarcate policy domain, many of our common challenges know no borders, whether arising from environmental pollution, degradation of river basins and glaciers, or viruses. An uncooperative neighbourhood in this context comes at a cost – one that is too heavy to be carried on the shoulders of a malnourished population.

Figure 6 Water stress regions, the ratio of water withdrawals to supply by 2040

A way forward

Why does the uncooperative situation persist despite the enormous risks to the very survival of the people in the region? The argument thus far for continuing the status quo is based on the hostile neighbourhood being taken as an exogenous factor. The decisions of the state are then a reflection of the priorities mandated by regional politics. Agency for change is minimal. There are very limited stakes in each other’s economies and therefore no substantial, vocal constituencies that lose out when relationships are fractured. Formal trade with India has hovered between 1.2 and 3.5 per cent of Pakistan’s trade in the last two decades. Seen from the Indian perspective it is even more insignificant – trade with Pakistan has stayed well within just half a per cent of its global trade in the same period. And while economic gains from cooperation in energy and water are unquestionable, it is also out of question to undertake cross-border investments from fear of being held hostage by the other. There is such little to be had, that it is no great loss when it is lost.

By dispensing with Indian Occupied Kashmir’s autonomy, Narendra Modi’s government has suffocated whatever little space there was for improving the relationship with Pakistan. Followed up as it was with the Citizenship Amendment Act later in the year, and suppression of protests against both acts, there is little ambiguity left about the appetite for peace in Indian leadership at the moment. There is some hope, however, for democracy to force a corrective path, driven not perhaps by a constituency for peace, but by an economic imperative. India’s growth has slowed successively, down now to 4.7 per cent this quarter, the slowest in seven years. The COVID crisis has come hot on the heels of the existing slowdown. There may yet be a window for a rethinking of national priorities and for embracing the vision of a cooperative neighbourhood.

While this vision needs political support to be plausible, it does not need a comprehensive settlement of all border disputes. China, for example, remains India’s top import partner and fourth most important export partner despite territorial disputes. In fact, China also maintains strong trade ties with the ASEAN countries, despite disputes over the South China Sea. Forging ahead with economic ties generates a virtuous cycle, building constituencies for peace and space for dialogue that can be leveraged to make progress on the politically sensitive “no-go” areas of bilateral relationships.

While India runs through the cycle of nationalist far-right politics, there are still ways for reasonable people on both sides to continue contributing to the vision of peace and cooperation, focusing on small gains that build trust and people-to-people contact, while avoiding politically charged items. Lower government involvement also lowers the risks of the derailment, generating space to develop the vision and groundwork required for peace outside of the minefield of Track 1 dialogue.

For trade, for example, while the political climate makes it difficult to push for free formal trade, limited informal border trade can build people-to-people contact and enhance the welfare of participating communities. The border haats established between Bangladesh and India in 2011 demonstrate these benefits. Initially, four borders haats were set up as a confidence-building measure, with only local produce permitted to be traded. Given the strong, positive response to the initiative, both the range of products traded and the number of haats have increased over time and demonstrated successes have included an increase in trust, in people-to-people connections, and in local jobs and income.

Other examples of small initiatives to promote trust-building and people-to-people contact include cooperative joint research projects and academic linkages. Initiatives such as the South Asian Economics Students Meet (SAESM) are a case in point. Inaugurated in 2004, this is a forum for young economists in the SAARC region to get together to present their research. Each of the SAARC countries takes turns to host the annual SAESM meet, which has continued interrupted despite fluctuations in the formal relationships. In addition to generating feedback and exposure for young researchers, it has helped form friendships and networks, building trust and contributing to ameliorate the ‘other’-isation prevalent in the formal media and politics. Academic collaboration is also an important way to claim intellectual space in the discussion of regional politics and economics. Similarly, cultural exchanges and health and religious tourism also provide safe pockets within which to continue to build relationships and trust. The Kartarpur Corridor illustrates this aptly. Built and inaugurated after the tumultuous border conflict in 2019, the opening of the corridor was received with unrestricted jubilation from the people in both Punjabs and across the Sikh community in India and beyond.

Other, more sensitive, topics can also benefit from a shift in approach. The issue of sharing the supply of waters, for example, is politically fraught and consequently seen as “difficult” – a zero-sum game that is competitive in nature. More water to one riparian comes at the cost of less water to another. An alternative approach is to shift focus towards a collaborative, demand-based approach that builds cooperation. In the early stages, this could take the shape of alignment of policies and management practices for joint eco-systems and basin-wide planning. Another less controversial area of water cooperation to start with is sharing experiences and data for similar challenges and their solutions, such as rainwater harvesting, less water-intensive agricultural practices, salinization in coastal regions, ecosystem protection and flood management (including sharing of early warning data). These also shift the focus from competitive to cooperative initiatives, where communities can work together and see local (and mutual) benefits immediately, which helps to re-visualise water as a source of benefit rather than conflict (Price 2016).

The Brahmaputra Dialogue is an interesting example of this type of approach. Initiated in 2013 under the South Asia Water Initiative, it involved the four riparian countries of the Brahmaputra Basin: China, India, Bangladesh and Bhutan. The Dialogue started as an informal platform of Track 2 and Track 3 dialogue, to initiate conversation between representatives of states, civil society, academia, etc. across the four countries. The initiative focused on jointly identifying and developing common themes such as institutional mapping, disaster management, inland water navigation, and the water-energy nexus, building trust and consensus at each stage to ensure participation and ownership, and has eventually become an important input into breaking the deadlock over the basin. It has been successful in building trust and developing avenues of cooperation beyond the signing of treaties and sharing hydrological data that typically result under Track 1 dialogues.

The Chaophraya Dialogue and the Chao Track are examples of such initiatives between India and Pakistan, which have consistently brought experts on water and climate change from Indian and Pakistan to discuss ways in which both countries can devise cooperative mechanisms on transboundary water resources, in addition to the more strategic challenges of conflict stabilisation and peacebuilding. Run for more than a decade now, the Chao Track has had India and Pakistan’s ranking diplomats, senior policymakers and opinion leaders formulate options on Kashmir, strategic stability, peace across the LoC, countering violent extremism and building narratives for peace. It has operated close to Track 1 policy and in recent years become the strongest channel for interlocutors to debate and convey key recommendations for governments on both sides, in the absence of any official bilateral channel. The Chao Track’s Young Leaders Forum also ensures participation from the second cohort of younger practitioners who can influence both policy and public discourse. Expanding initiatives such as these would ensure that groundwork on building a cooperative neighbourhood continues even in politically volatile times.

The Pakistan-India relationship is the elephant in the room for South Asian cooperation. The time for this relationship to amend its current unproductive course is now when economic growth rates and a health pandemic can act as a stimulus for change. Both the vision of a prosperous and peaceful South Asia and the human development imperative to shift away from the hostile status quo are in place. Pakistan and India can choose now to participate in developing the South Asian success story, building constituencies for peace that will allow politics to finally follow the economic and ecological realities of their people. Or, in the words of Roy, they can choose to drag the carcasses of their prejudice and hatred behind them as they step into the future. This essay was first published on the Jinnah Institute’s website.

Nazish Afraz is a Teaching Fellow at the Department of Economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). She has worked in public policy research in the UK and in Pakistan. Research interests include industrial development and trade. She has completed an MPhil in Economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and an MSc in Economics and Finance from the University of Bristol.

Nazish Afraz is a Teaching Fellow at the Department of Economics at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). She has worked in public policy research in the UK and in Pakistan. Research interests include industrial development and trade. She has completed an MPhil in Economics from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and an MSc in Economics and Finance from the University of Bristol.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia