In his book, Nomads and Soviet Rule: Central Asia under Lenin and Stalin (I.B. Tauris, 2018), Alun Thomas examines the experiences of Kazakh and Kyrgyz nomads in the NEP (New Economic Policy) period and demonstrates the Soviet state’s treatment of nomads to be far complex and pragmatic. He shows how Soviet policy was informed by both an anti-colonial spirit and an imperialist impulse, by nationalism as well as communism, and above all by a lethal self-confidence in the Communist Party’s ability to transform the lives of nomads and harness the agricultural potential of their landscape. This is the first book to look closely at the period between the revolution and the collectivization drive, and offers fresh insight into a little-known aspect of early Soviet history.

VCA: Your study provides important insights into Communist politics towards nomads since early Soviet times. The book’s introduction makes the point that this is the period between the revolution and the collectivization drive. What was this period about? Who was in charge? Were there debates around how to treat the nomads and what were they about?

AT: My book looks primarily at the period of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which lasted roughly from 1921 to 1928. The NEP was not applied in a systematic fashion; its effects were felt differently in different places. This makes it tricky to define. It might even be said that what makes the NEP a coherent period of time is what it wasn’t. It wasn’t Civil War, accompanied by ruinous violence, and it wasn’t the first Five Year Plan and collectivization, accompanied by a highly destructive confiscation drive.

This would be an exaggeration though. There was plenty of violence in the NEP era too, not least because of the so-called Basmachi uprising. There were also distinctive patterns in the treatment of nomads in the NEP era, and one had to do with the NEP itself; the Bolsheviks made an effort to establish a standardized tax system that taxed nomads in a proportionate manner, sensitive to their way of life. The NEP also coincided with the Bolsheviks’ ‘national delimitation’ of Central Asia, which divided the region into the five nation-states we have today, and this had profound physical and conceptual impacts on nomadic life.

This would be an exaggeration though. There was plenty of violence in the NEP era too, not least because of the so-called Basmachi uprising. There were also distinctive patterns in the treatment of nomads in the NEP era, and one had to do with the NEP itself; the Bolsheviks made an effort to establish a standardized tax system that taxed nomads in a proportionate manner, sensitive to their way of life. The NEP also coincided with the Bolsheviks’ ‘national delimitation’ of Central Asia, which divided the region into the five nation-states we have today, and this had profound physical and conceptual impacts on nomadic life.

Central Asian nomads were governed in the NEP period by a mixture of loyal Bolsheviks and local elites with whom Moscow had made an uneasy pact. There was a general consensus that nomadic life was ‘backward,’ but beyond this, there was a lot of disagreement about nomads in the 1920s. Some thought the Party needed to incentivize permanent settlement among nomads, for example, while others felt there was no need to intervene.

VCA: How would you describe the Tsarist policy towards the nomads? What were the Tsarist administrators planning regarding the region? Was Tsarist and Bolshevik policy different regarding the European/Russian settlers?

AT: Nomadic experience under the Tsar varied a lot depending on when different regions came under St. Petersburg’s control. Russian influence over the northern Kazakh Steppe came long before the Russian Empire reached the Tian Shan. The Empire made its presence felt in changing legal customs, in schooling, and in structures of authority; but probably its biggest impact from a nomadic perspective came from settler colonialism. Russian peasants arrived in nomadic areas in large waves in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and they tended to acquire the best pastureland, creating much hardship for nomads.

In the early 1920s, many of these European settlers (not only Russians, of course, but others from the western periphery of the former Empire, such as Ukrainians) were forced to leave Central Asia as local nomads reclaimed their pastureland. It seems the Bolsheviks were unsure how to respond. They were caught between two impulses; first, to support processes of decolonization and evince their anti-imperialist ideology; second, to sustain and develop the Soviet economy. Remember that they thought of nomadism as backward. The national delimitation might be thought of as a way for them to resolve the tension between these impulses, but I think the nomadic experience shows that this was near impossible.

VCA: Soviet anti—nomad politics affected not only Kazakh and Kyrgyz but also Turkmen nomads, maybe nomads in Siberia too. Do you know if politics were the same? Or were there differences?

AT: I think this is an open question. Local factors played a huge role in nearly every decision made by the Party regarding nomads, so there will no doubt be variation. The impact of collectivization on nomads was nowhere as bad as it was in Kazakhstan, for example.

However, there are some trends which, in all likelihood, apply in all cases. Moscow had a specific way of understanding space as both national territory and economic resources. This governing mentality cascaded down to Communist Party committees and cells in the form of demands for information and resources. In any nomadic region of the USSR, I’d argue, it was then confronted by a different way of valuing and mapping space. When nomads declared their right to use or migrate through land-based upon their own authorities of custom and practice, the Communist Party argued back with talk of national jurisdiction and macroeconomic targets. The nomadic tendency to migrate made some land seem unoccupied or under-utilized, but to nomads, this land was essential to their wellbeing. In contrast, the Soviet Union took its borders very seriously, but for nomads, these borders were trivial annoyances at best and obstacles to their survival at worst.

VCA: Soviet attempts of eradication nomadism could be designated as “carrot and stick policy”. It was a combination of coercion and attraction: higher taxes for nomads, de-kulakization and collectivization campaigns together with educational programs. What were the other carrots? Only education?

AT: I think it’s important to note that most Communist Party members assumed that the nomads were desperate to settle if they felt able to. Some Bolsheviks argued that nomadic elites, the bai and manaps, maintained their power by keeping their communities in a state of migration and thereby keeping their communities impoverished and docile. So there was some surprise in the Communist Party that the arrival of socialism did not create a surge of permanent settlement. Incentives were something of an afterthought.

We have to be cautious of the historical sources, which surely exaggerate the number of resources actually offered to settle nomads. In principle, the Communist Party committed itself to the distribution of timber to make new permanent dwellings, and it committed resources to make successful new farmsteads. Peasants were asked to help to settle nomads to learn productive methods of farming. Nomads who had recently settled were taxed at a lower rate than those that migrated, though tax-collectors reported that nomads often claimed to have settled so that they’d pay less tax, and then simply continued to migrate once the tax-collector had moved on. These kinds of administrative headaches—associated with a highly mobile population—vexed Bolshevik authorities throughout the decade.

VCA: Were the local people consulted about the policy? There have been many discoveries that indicate the local elite had participated actively in the central Soviet policies. What would you say about this?

AT: These cases open up interesting opportunities to talk about power and accountability in Soviet Central Asia. Partly, this is a question of which categories we use to understand history. Do we divide up participants by their class, as the Bolsheviks might, or by their ethnicity, their language, their tribal or clan loyalties, their gender, or by their everyday behaviors?

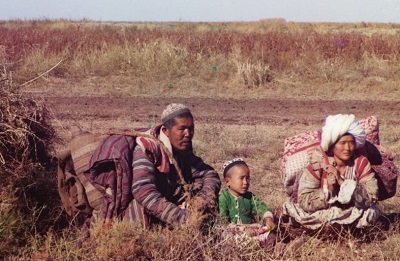

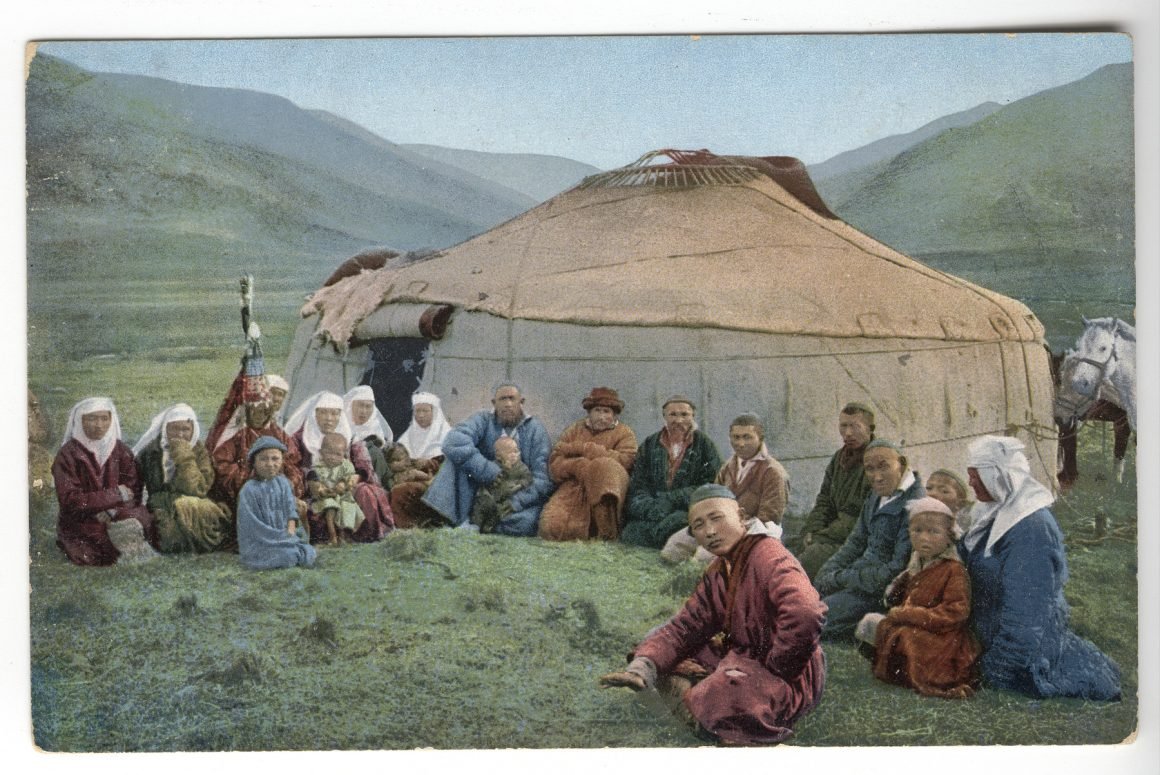

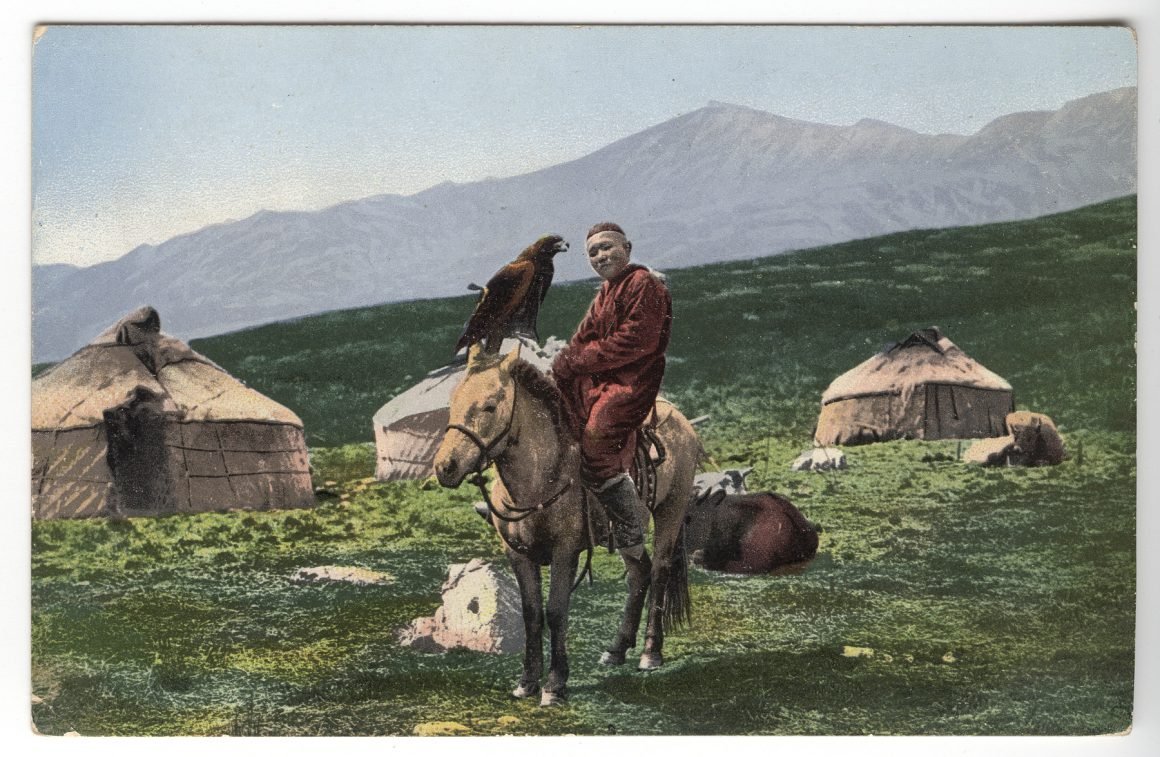

The Kyrgyz nomads. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

The Kyrgyz nomads. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

To simultaneously be both a Communist Party administrator and nomadic was very difficult. With some exceptions, like the Red Caravan expedition or the Red Yurts campaign, Soviet centers of power tended to be sedentary and urban. Central Asian elites in the upper echelons of their local Communist Party branch ideally had to be literate and proximate to the bureaucracy. As such, in the book, I tend to emphasize the isolation of nomads specifically from the Soviet state and its decision-making processes.

A caravan of camels carrying thorns for food. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

A caravan of camels carrying thorns for food. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

Yet there was certainly an overlap. Nomadic communities did learn the language of the new regime and could deploy it when needed. When disputing the use of natural resources, for example, nomads sometimes spoke of national representation and the good of the larger Soviet economy. When collectivization began, some tribal elites used the state’s facility for violence against members of rival tribes.

VCA: What is the greatest mistake of the policy that led to the tragedy of collectivization? How big was this tragedy, and how has it affected the region through today ? Were there any alternatives?

AT: Although it’s mainly focused on the NEP years, it was essential that my book contains a chapter on collectivization because of the existential impact the policy had on Central Asian nomadism. The collectivization campaign began in 1928 and the Soviet countryside did not begin to recover until 1934. Kazakhstan was one of the largest nomadic regions of the USSR, and as a proportion of their population, Kazakhs suffered more deaths from collectivization than any other nationality. Approximately one and a half million people died as a result of collectivization in the Kazakh Republic.

Local sheep. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

Local sheep. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

Nomadism interacted with collectivization in a number of ways. The perception that nomadism was backward helped to justify the extreme measures taken. The confiscation of resources, particularly livestock, drained an economy that was also suffering shortages and destabilization. The regime’s insistence that collectivized nomads should settle—what the Party called ‘sedentarization’—was an absurdity in a landscape that was unsuitable for sedentary farming. By the mid-1930s, the number of nomads in Central Asia had dropped precipitously.

Nazar Mohammed. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

Nazar Mohammed. Hungry Steppe. Photo by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, 1909-15

The NEP years show that the Communist Party was willing to make accommodations with nomadism and to meet nomads in their own land on their own terms.

I struggle to envision any alternative regime in Central Asia after the collapse of Tsarism which was supportive of nomadism. Local political elites who only joined the Communist Party after the Civil War tended to be modernizers who saw nomadism as a hindrance. But the NEP years show that the Communist Party was willing to make accommodations with nomadism and to meet nomads in their own land on their own terms. From my perspective in the 1920s, the cardinal changes leading to sedentarisation occurred at the end of the decade in the high politics of the USSR. Courtesy: Voice on Central Asia.

Dr Alun Thomas’s work relates to the postcolonial nature of early Soviet governance in non-Russian regions of the USSR. He has researched on the modern history of Russia and Central Asia. He began his doctoral studies in September 2011. His doctoral thesis, ‘Kazakh Nomads and the New Soviet State, 1919-1934’ described the treatment of nomadic peoples by the Communist Party in the early Soviet period. It built upon original research in archives in Almaty, Kazakhstan and Moscow, Russia.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia