There are lives so fused with their art that no simple boundary can be drawn between the person and the poem. Akhtar Sherani and Abdul Hameed Adam were poets whose verses shimmered with longing, whose biographies bore the same marks of indulgence and vulnerability that their couplets hinted at, and whose reputations rose to extraordinary heights only to recede in the collective memory of our language. They were, each in his way, emblems of an Urdu literary culture that treasured both aesthetic refinement and personal candour, and that was never entirely sure whether to admire them for their luminous art or to pity them for the shadows it cast over their private lives. It is this fertile, complex territory that Muhammad Akram Saeed has chosen to explore in two thoughtfully compiled volumes, Āp Kā Akhtar Sherānī: Shakhsī Khākē, Tajziyah aur Matn (Your Akhtar Sherani: Biographical Sketch, Analysis, and Text) and Huzūr! Yeh Hain Adam: Tehqīq, Tajziyah, Matn (Sir! Here Is Adam: Research, Analysis, Text).

These are not mere collections of homage or casual anthologies of scattered essays. They are, more profoundly, acts of cultural recovery—exercises in drawing the full shape of lives whose contradictions were once the stuff of legend but risked becoming footnotes to literary history.

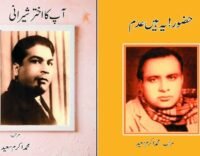

Aap Ka Akhtar Sherani: Shakhsī Khakā, Tajziya aur Matn, compiled by Prof Muhammad Akram Saeed.

Huzoor! Yeh Hain Adam: Tehqeeq, Tajziya, Matn compiled by Prof Muhammad Akram Saeed

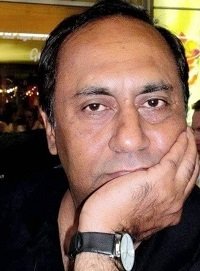

Prof Akram Saeed, born in 1949, approaches these projects with a combination of scholarly discipline and creative empathy that sets his work apart in contemporary letters. He spent twenty years teaching at Government College, Sheikhupura, before retiring in 2009. He has written extensively in both Urdu and Punjabi, with particularly notable contributions to Punjabi prose and poetry. His bibliography ranges across poetry, literary criticism, pen sketches, and anthologies, including a full-length critical study of Mansha Yaad’s influential Punjabi novel TanwaN TanwaN Taara. That breadth of engagement is perhaps what allows him to balance the demands of documentary precision with a generosity of interpretation—qualities that make these two books as compelling to read as they are essential to consult.

Sherani’s life reads almost like a parable of the perils and possibilities of romantic modernism in Urdu. Born as Muhammad Daud Khan in 1905 in the princely state of Tonk, he inherited from his father, Hafiz Mahmood Sherani, a formidable legacy of scholarship and expectation. Yet it was apparent early on that the son’s vocation lay elsewhere. Sherani’s devotion to verse was uncompromising, and he became the first poet in Urdu to address his beloveds—Salma, Azra, Rehana—by name, giving his poems an immediacy and audacity that startled and enchanted readers. For the first time, the romantic ghazal spoke with a voice unafraid to name desire openly, to acknowledge the presence of a woman as something more than an allegorical phantom. His language was soft as velvet, musical in its cadence, painting longing in colours that seemed both intimate and universal. In collections such as Phoolon Ke Geet, Akhtaristan, Shahnaaz, and Shahrud, Sherani built a lyrical cosmos that inspired a generation seeking expression for emotions they had been taught to conceal.

Yet the price of such intensity was steep. From an early age, Sherani succumbed to the allure of alcohol, and drink became both a companion to his creative ecstasy and the instrument of his decline. Those who knew him remembered gatherings in Lahore where he presided over literary conversation with a weary, ironic detachment, as though aware he was burning through his gift faster than any poet should. By the time of his death in 1948 at just forty-three, Sherani was as much a cautionary figure as an exemplar. His decline, however, never diminished the singularity of his accomplishment: he had given Urdu verse a new emotional register, and in doing so, forever altered its landscape.

Abdul Hameed Adam, though a younger contemporary, shared with Sherani the reputation of a poet who turned his appetites into the subject matter of his art. Born in 1910 (some records note 1916) in Gujranwala’s Talwandi Musa Khan village, Adam spent most of his life working in military accounts and retired as a Deputy Controller in 1966. Where Sherani was celebrated for a kind of delicate, musically inflected romanticism, Adam became famous for a voice that was colloquial, direct, and curiously disarming in its simplicity. His couplets were as likely to evoke the pleasures of an evening drink as the sorrow that follows it, and this tension between indulgence and regret gave his poetry a flavour distinct from any of his peers. Collections like Nakshe Dawam, Kharaabat, Gardish-e-Jaam, and Shahr-e-Khooban were widely read and quoted, their lines finding their way into ghazal recordings by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Tahira Syed, into popular songs, and into everyday speech.

Yet Adam too saw his renown diminish as literary trends shifted away from romantic and hedonistic themes toward the politically engaged. By the time he passed away in Lahore in 1981, the cultural moment that had once lifted him to extraordinary popularity had already moved on. What remained were the couplets themselves, still circulating in the memories of those who valued their unpretentious candour and melancholy grace.

Against this backdrop of fading reputations and fragmentary recollections, Akram Saeed’s books take on the character of an intervention. Aap Ka Akhtar Sherani assembles twenty-six entries that include essays, sketches, personal remembrances, two examples of Sherani’s poetry, and a bibliography. These perspectives do not flatten the poet into a legend or a cautionary tale. They present him in all his contradictions: a gifted editor of literary journals, a pioneer who experimented with sonnets and folk forms, a lover whose devotion to beauty could not save him from ruin.

The volume’s editorial strategy—juxtaposing affectionate recollections with sober analysis—creates a composite portrait that is moving precisely because it never tries to reconcile Sherani’s strengths and weaknesses into a single moral. Saeed, in his foreword, insists that such simplification would betray both the poet’s legacy and the record of those who witnessed it firsthand. His method is to document, not to resolve; to present evidence, not verdicts. This refusal to tidy up Sherani’s life is what gives the book its rare integrity and its haunting emotional charge.

Huzoor! Yeh Hain Adam adopts a similarly inclusive approach, though it radiates a slightly more intimate tone. The sixteen pieces at the book’s core—including the last interview with Adam—explore his unique position as a poet whose work was both widely accessible and subtly layered with philosophical resignation. Writers like Sayyed Zafar Hashmi, Shakeel Badayuni, and Hafiz Nazar Siddiqui bring into relief an Adam who chronicled ordinary life without condescension, who acknowledged the pull of pleasure without apology, and who somehow managed to transform his failings into a form of disarming honesty.

One of the most striking aspects of these essays is how they return, again and again, to the sense that Adam’s public persona—a man who seemed to embrace life’s indulgences without regret—was in tension with a deeper solitude. As with Sherani, the portrait that emerges is not one of neat closure but of a life still radiating questions.

Taken together, these two books achieve something rare in contemporary Urdu literary scholarship: they create an archival space that resists both nostalgia and condemnation. They do not attempt to canonise Sherani or Adam as exemplary figures, nor do they present them as cautionary examples. Instead, they insist that literature, like life, is never reducible to a single storyline. Sherani’s velvet-lined romanticism and Adam’s colloquial melancholy are preserved here in all their complexity—each reminding us that the contradictions in a poet’s life are often the very conditions of their art.

Reading these volumes is like stepping into a room filled with voices—some celebratory, some regretful, some analytic, some wounded—and realising that no single perspective can claim final authority. You sense how the adulation these poets once commanded was as much a reflection of their readers’ hunger for self-expression as it was of their originality. You also recognise that their subsequent decline in popularity was not simply a matter of aesthetic failure but the inevitable result of a culture always in search of new idioms.

Yet if literary fame is fickle, these books remind us that the deeper impulse to seek beauty, to name longing, to affirm life’s fragile pleasures, remains constant. Sherani’s insistence that love be spoken of openly, Adam’s unguarded celebration of experience—these are not merely relics of another time but enduring testimonies to the human desire to make meaning out of transience.

In an age increasingly impatient with ambiguity, when so many demand clarity and moral certitude from their artists, the stories of these two poets feel especially instructive. They show us that art is rarely a tidy account of virtue or vice. More often, it is an uneasy truce between what we aspire to be and what we cannot help but become. In that truce lies not only the risk of failure but the promise of something irreplaceably alive.

For anyone who believes that literature’s task is not simply to affirm our better selves but to illuminate our contradictions, Aap Ka Akhtar Sherani and Huzoor! Yeh Hain Adam will be indispensable. They are, in the end, more than literary anthologies. They are invitations—to remember, to reconsider, to feel more fully the difficult and necessary truth that a poet’s work, like the human heart itself, is never finished.

Dr Aftab Husain is a Pakistan-born, Austria-based poet who crafts verse in Urdu and English. His work bridges cultural and linguistic landscapes. He is a scholar of South Asian literature and culture, which he teaches at the University of Vienna.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia