Fears for a legendary art collection in the desert town of Nukus led to activists and volunteers preserving the treasures۔

By Amos Chapple

Fears for a legendary art collection in the desert town of Nukus led to activists and volunteers preserving the treasures with photographs on a new website.

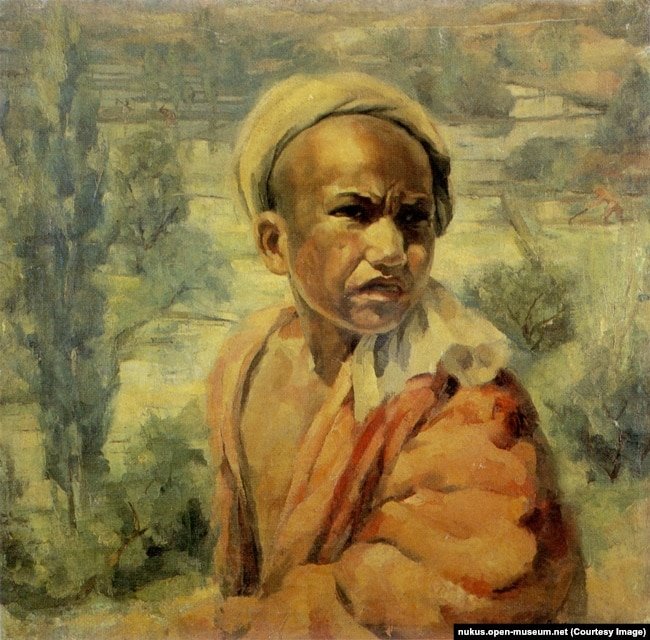

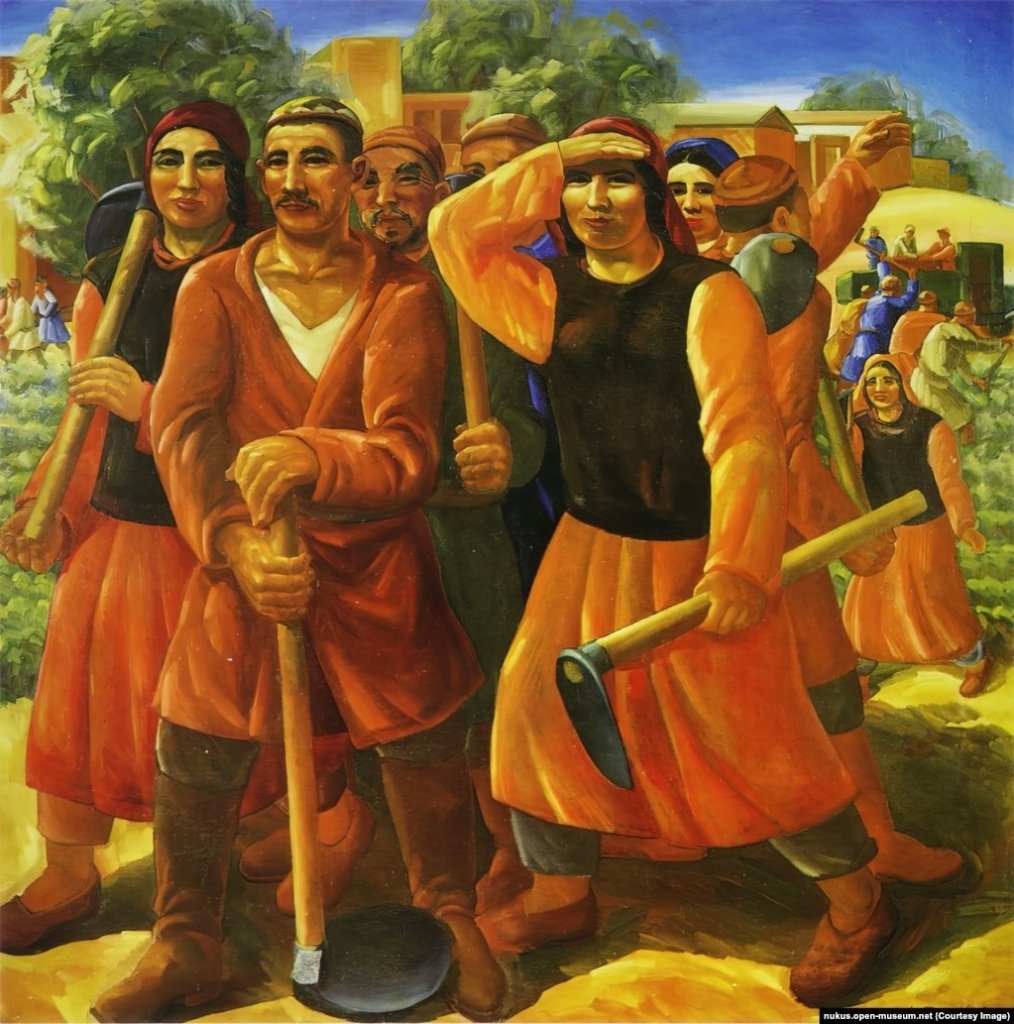

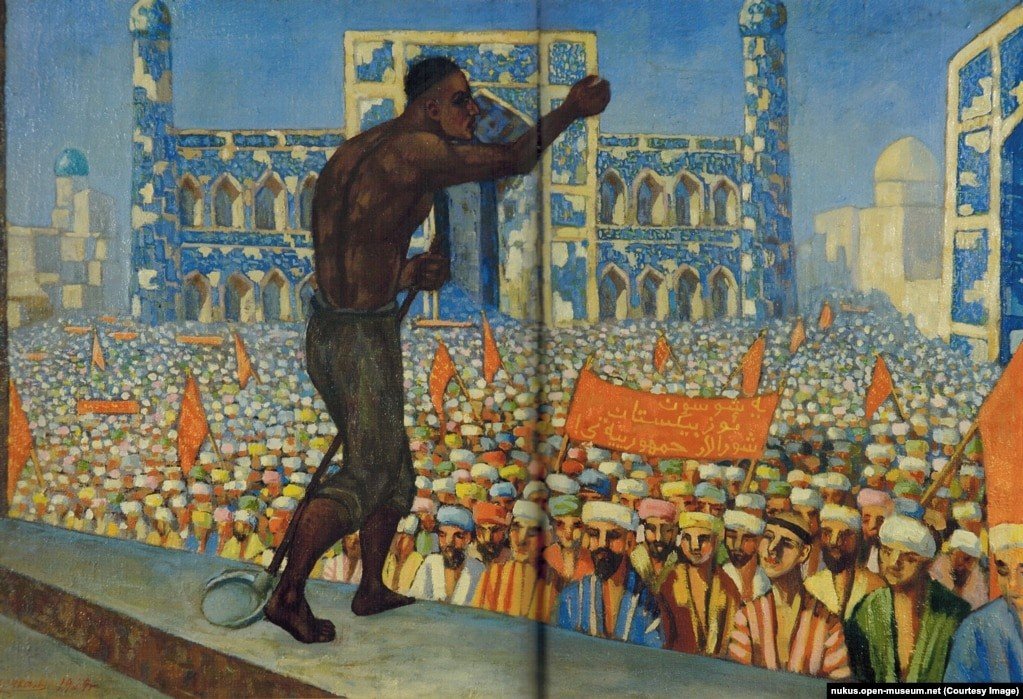

Nine hundred pieces from Uzbekistan’s Nukus Museum of Art are now online after volunteers armed with cameras and cell phones created an open catalogue of the works in the hope it will prevent theft from one of Asia’s most unique and valuable art collections.

The Nukus Museum, in Uzbekistan’s desolate Karakalpakstan region, was established in 1966 after Russian artist and archaeologist Igor Savitsky convinced the local authorities that the area needed a facility to house mostly local cultural artefacts.

The facility gradually grew into a trove of forbidden art thanks to Savitsky’s collecting trips, including to Moscow, where he met with the relatives and widows of artists whom the Soviet authorities had banished to obscurity or the gulag, or had executed.

Thanks to personal connections and his far-flung base in Nukus, Savitsky was able to quietly amass tens of thousands of works by blacklisted artists hidden in private homes. The collector in some cases used state funds to purchase the work of avant-garde creatives whose work was condemned as “degenerate” by the Soviet authorities. Savitsky’s daring acquisitions have been compared to someone using Taliban funds to collect a vast stash of Buddhist sculptures. Savitsky focused especially on artists with links to Central Asia, or who painted Uzbek scenes.

After Savitsky’s death in 1984, the museum was run by his handpicked successor Marinika Babanazarova. When the highly-respected Babanazarova was fired by the Uzbek authorities in 2015, many feared the artwork she had overseen would become vulnerable to theft in the notoriously corrupt country. Some of the paintings in the Nukus museum are worth millions of dollars each, and there are more than 82,000 artworks in total in the museum’s collection.

Following Babanazarova’s controversial dismissal in 2015, a project to digitize the Nukus art and publish it in an online public catalogue online began. Svetlana Gorshenina, a Paris-based historian, and Montreal-based curator Boris Chukhovich founded the Alerte Héritage Observatory website.

Gorshenina told RFE/RL that the push to create a public record of the Nukus art became urgent after “at least one work by Aleksandr Volkov from the collection of the Ferghana Museum appeared at an auction in London, replaced, we believe, by a copy on the walls of the museum.”

Gorshenina says having photos of the most valuable of the museum’s artworks on a publicly accessible website will serve as a reference point if there is suspicion of a forgery replacing the original. “The fact is, it’s impossible to make an exact copy of any painting, so if the image [of the original] is known then it serves as a safety mechanism for museum collections.”

Savitsky had deliberately sourced little-known artists for the museum, meaning that the Nukus collection is now the only repository for many of the artists’ work, potentially making fraud especially difficult to detect.

According to Gorshenina, the digitization project was entirely a grassroots effort, with volunteers taking snapshots on cameras, or even cell phones in some cases, of the art on display. Researchers then made short biographies wherever possible of 124 artists whose work is held in the Nukus Museum. Many of those artists would today be forgotten if not for the museum and its founder.

Today, Gorshenina says the website cataloguing the precious collection represents “by far the most complete collection of reproductions of the works of the Nukus Museum ever published anywhere.” –RFE/RL

Amos Chapple is a New Zealand-born photographer and picture researcher with a particular interest in the former USSR.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia