Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro on the ornate and unique graves that tell a story of timber, power and upheaval

Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro on the ornate and unique graves that tell a story of timber, power and upheaval

by Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

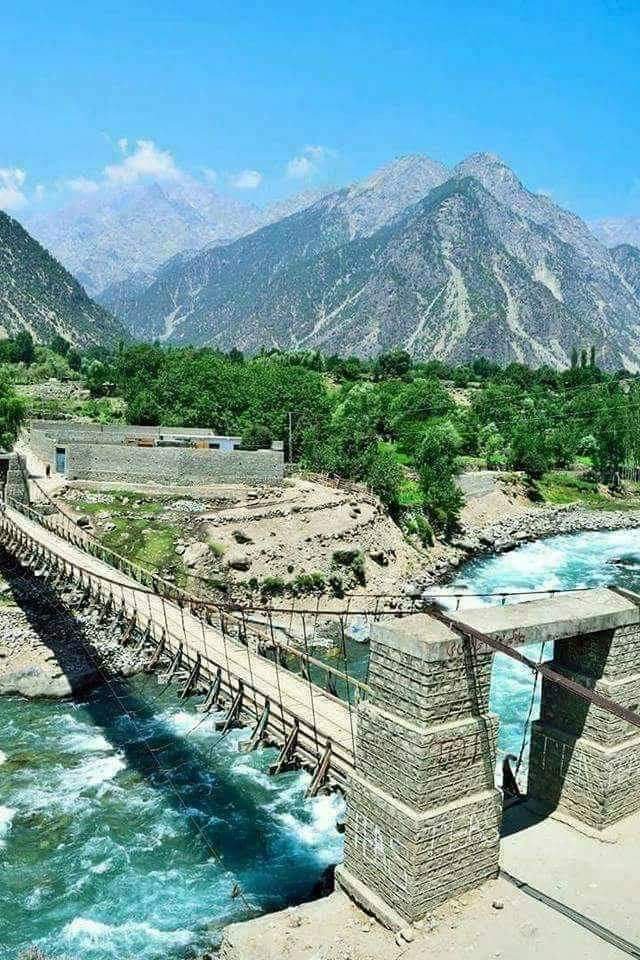

here are many carved wooden grave railings in Tangir and Darel in Diamer district of Gilgit-Baltistan. Such monuments are also located in many areas of Indus-Kohistan, Dir-Kohistan and Swat-Kohistan in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa where I am doing research for my forthcoming book Wooden Funerary Art in Dardistan.

These wooden grave railings exist in a number of villages in Tangir. Of these Mahechar, Khamikot, Faruri, Phaphat, Mushke are prominent. However, the wooden railings at Mushke and Khamikot villages are in good condition while those at Mahechar, Faruri and Phaphat have crumbled to pieces. The wooden planks and turrets (guldastas) are spread all over the site.

These wooden grave railings exist in a number of villages in Tangir. Of these Mahechar, Khamikot, Faruri, Phaphat, Mushke are prominent. However, the wooden railings at Mushke and Khamikot villages are in good condition while those at Mahechar, Faruri and Phaphat have crumbled to pieces. The wooden planks and turrets (guldastas) are spread all over the site.

Like Jaglot (headquarters of Tangir), Khamikot was an important town during the rule of Pakhtun Wali Khan. Now, it is a small village boasting some monuments of historical significance, the most prominent of which are the wooden mosque, the tower of Dost Muhammad and several finely decorated wooden coffins.

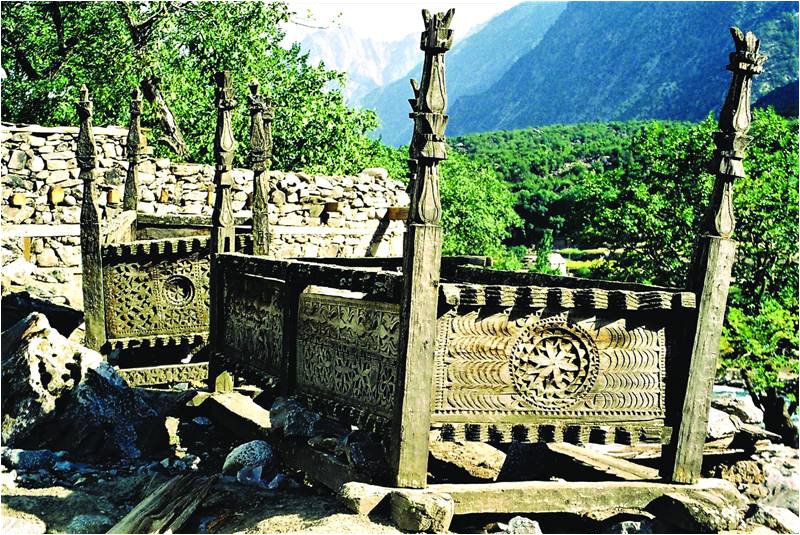

There are nine graves located adjacent to Khamikot mosque. All the graves are marked by carved wooden railings, with their sides highly carved and topped over by four leg-like turrets at the four corners. But the legs are placed in a reverse fashion, upside down. Each face of the coffin box consists of two wooden planks, each of them showing different designs of scroll work separated by a wavy line.

All burial places in Khamikot are marked with carved wooden coffins bearing a variety of floral and geometric designs. All the wooden boxes consist of two carved panels, one on either side, topped by four leg-like turrets. The wooden railing is placed over a frame below and not directly fixed into the ground.

The principal wooden coffin belongs to Pakhtun Wali Khan. The wooden railing is ornately carved and decorated with floral designs. Pakhtun Wali Khan ruled over the valleys of Darel, Tangir, Harban, Sazin and Shatial. He belonged to the Khushwaqte, the ruling family of Yasin, a branch of the Chitral dynasty. The British called the Indus valley below Chilas and its tributary valleys like Darel, Tangir, Kandia and many smaller communities Yaghestan: “Land of the Free” or “Land of the Wild”. Pakhtun Wali Khan ruled the roost here and exploited the rich resources of Tangir and Darel.

Barring Pakhtun Wali Khan, no one else could establish rule over the turbulent Tangir valley. Today, the carved wooden graves of all these dignitaries lie in a state of disrepair

During the British siege of Chitral in 1895, Pakhtun Wali Khan fled to Tangir. Through his bravery, soon he impressed the local population and established his rule in Tangir in 1905. Gradually, he extended his control to neighbouring valleys of Shatial, Sazin and Harban. For the twelve years (1905-1917) he ruled over the areas without encountering any local uprising until he was killed in 1917 by his servants at Khamikot.

The timber trade played an important role in Pakhtun Wali Khan’s power. The upper parts of both Darel and Tangir were covered with thick forests. Contractors belonging to the Kakakhel Pakhtun clan of Nowshera got timber cut in the high areas of the valleys and rafted it down the rivers. Pakhtun Wali Khan was eventually killed by his servants. Schomberg writes in his Between the Oxus and the Indus, that when the ruler was attending the building of a new house at Kammi (Khamikot), he told his servants to set aside their arms and help in this meritorious work. Wali had a bath, and then sat in a chair with his pistol lying beside him on the ground. He had a cloth over his shoulders, for his head was being shaved. There were many men passing near the Raja, carrying bricks and mortar. Suddenly, several men attacked him, hitting him on the head with an axe. He bent down for his pistol, but was struck four or five times and died without being able to defend himself’.

Pakhtun Wali Khan is said to have built a number of mosques and forts in his dominion which are located in many villages and towns of Darel, Khanbari, Sazin, Harban and Tangir. The fort that he was supposed to have built in Gumari, Darel, is now in ruins – reminding the visitors of the past glory of the city.

Pakhtun Wali Khan was buried near Khamikot mosque where today his burial place is marked by a carved wooden railing which is believed to have been made by the notables of the Khamikot village. This wooden railing is more beautifully decorated than the nearby railings that belong to Mohiuddin, Raja Sifat Bahadur, Faqir Wali and Amir Hyder, respectively.

Next to Pakhtun Wali Khan’s railing is located the wooden grave coffin of Mohiuddin, a Khushwaqte prince who lived at Dain village in Ishkoman. The fertile lands of Tangir also lured him. He tried to seize the suzerainty of Tangir but was killed by Raja Sifat Bahadur, another contender for the throne. Mohiuddin was attacked and killed in his house at Jaglot by Raja Sifat Bahadur. This Khushwaqte prince’s dream of ruling Tangir did not come true. He was buried in the same graveyard where the wooden coffin of Pakhtun Wali Khan is located.

Like Mohiuddin, Raja Sifat Bahadur also tried to seize the suzerainty of Tangir but could not succeed in his objectives and was killed by his own trusted servant. He was buried next to Mohiuddin. His son Amir Hyder and his nephew also faced the wrath of the Tangiris and they were killed. The wooden coffins of Amir Hyder and Faqir Wali stand close to the wooden enclosure of Raja Sifat Bahadur, a governor of Yasin who tried to capture Tangir and its rich forests. Barring Pakhtun Wali Khan, no one else could establish rule over the turbulent Tangir valley. Today, the carved wooden graves of all these dignitaries lie in a state of disrepair.

Apart from Khamikot, there are more than thirty carved and simple wooden coffins located in Mushke village.

There are two villages in Darel valley – Manikyala Bala and Manikyala Pain where one finds some carved wooden coffins. In Manikyala Bala, there are some impressive wooden grave railings particular at Lashnokot. Apart from that, there are a few carved wooden grave railings at Phuguch village. These wooden monuments carry both floral and geometric designs. Apart from that, there are some wooden grave railings of lesser interest in the village of Yeshot.

As far as the decoration of these railings is concerned, it appears that inspiration has been taken from the decorated pillars of various wooden mosques of Darel and Tangir while making these wooden coffins. Wooden mosques at Gayal, Phuguch, Somigal Bala, Somigal Pain, Manikyala Bala and Manikyala Pain are noted for their spectacular ornamentation.

The tradition of making wooden grave railings still continues in Tangir and Darel, although they are now simple and undecorated. It is worth noting that in Tangir social memory plays a very important role in preserving the names and achievements of the dignitaries buried under these imposing wooden funeraries. Tangiri and Dareli people express great pride in transmitting their oral traditions to the new generation and expect them to continue the same for the coming generations. This feature was first published in The Friday Time July 19, 2019

![]() Dr Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro is an anthropologist and has authored four books: ‘Symbols in Stone: The Rock Art of Sindh’, ‘Perspectives on the art and architecture of Sindh’, ‘Memorial Stones: Tharparkar’ and ‘Archaeology, Religion and Art in Sindh’. He may be contacted at: zulfi04@hotmail.com

Dr Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro is an anthropologist and has authored four books: ‘Symbols in Stone: The Rock Art of Sindh’, ‘Perspectives on the art and architecture of Sindh’, ‘Memorial Stones: Tharparkar’ and ‘Archaeology, Religion and Art in Sindh’. He may be contacted at: zulfi04@hotmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia