I was going to write about the happenings in this northwestern corner of Pakistan in the foothills of Khyber Pass, but the death of a dear friend in Karachi pre-empted my plans.

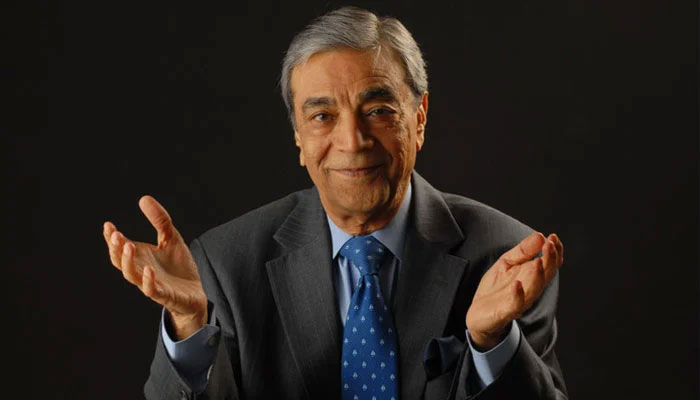

Today, the entire country of Pakistan, the Urdu speaking Indians, and the Urdu Diaspora around the world are mourning the passing of Zia Mohyeddin, a man of Urdu, English, and Persian letters, a superb orator, a musician par excellence, an actor, and a custodian of age-old cultural traditions of Indo-Pakistani Subcontinent.

He was 91 years old.

He was a versatile man. Brought up in Pakistani Punjab, he was deeply steeped in Urdu, Persian, and Punjabi culture, music, and literature.

Love of spoken word and a flare for theater took him to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London in the early 1950s.

Thereafter, he had a successful career as a movie actor (Lawrence of Arabia, Passage to India, Behold a Pale Horse) and on and off West-end stage in London (Long Day’s Journey into the Night, Julius Caesar, A Passage to India).

Most recently he was the head of the National Academy of Performing Arts in Pakistan, which he founded in 2005.

In the 1990s, he brought back the almost lost art of public reading of Urdu and English essays.

With his training as a stage actor and his diction, he could captivate the audience with his one-man shows.

He was already a well-known literary and screen personality when our paths crossed in the early 1990s at a dinner party in New York.

Lucky for me, the guests mostly consisted of Pakistani politicians, bankers, physicians, and a sprinkling of academics.

Their kind, by and large, is not into the fine arts or literature.

I gave him my recently published Urdu book, and he promised to write to me. To my surprise he sent me a hand-written letter commenting in detail on various aspects of the book.

Furthermore, he wrote about our meeting in New York in his weekly English column in the Pakistani newspaper the News International.

Over the years, he visited Toledo many times to perform at private gatherings, mostly at my residence.

Our limited circle of Urdu lovers in Toledo always looked forward to his visits.

In fact, many friends from other parts of Ohio and Michigan would also come to enjoy his wit and wisdom.

In late 1990s, we started writing occasional letters to each other on literary and cultural issues.

He wrote in a simple and informal style of letter-writing popularized by the 19th century Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib.

Over the years we wrote dozens of letters on myriad subjects.

Later, those letters were published in a book.

During the coronavirus pandemic our regular literary sittings at my home came to a stop. To revive the 25-years old tradition, we resorted to Zoom Meetings.

I asked Zia Sahib (he was addressed by his friends and fans as Zia Sahib) if he would consider reading a few of his letters that he had written to me. He agreed but suggested we both read the letters we had written to each other.

It was a unique literary exercise.

About 20 years ago when we met during one of his periodic visits to the U.S., I brought up the subject of risqué Urdu poetry and lamented that while such poetry is popular in private circles, the academic world has shown little or no interest in this genre.

He agreed and mentioned T.S. Elliot and Urdu poets Mir and Zauq who had written in that genre.

I had already collected a book-worth of such material in Urdu.

I asked if he would help obtain material written by some of the great Urdu poets. He not only promised, but he also offered to write the foreword as well.

We collaborated on two such books and he wrote forewords for both.

In one case, he tracked down a lost manuscript, had it copied, and mailed it to me. When that got lost in transit, he repeated the process.

He also wrote cover blurbs for a few of my English books.

He published several books of English essays.

These included A Carrot is a Carrot, Theatrics, and The God of my Idolatry.

In A Carrot is a Carrot, he writes about his encounters with some of the great stage actors and writers, such as Lawrence Olivier, Tennessee Williams, Dylan Thomas, and EM Foster.

To say Zia Mohyeddin was a legend would be an understatement. He was much more than just a legend.

He revived performing arts in Pakistan and helped bring classical music to the attention of the common people.

He fought against those who wanted to banish theater, literature, music, and fine arts to oblivion and won.

He was a man for all seasons.

S. Amjad Hussain is an emeritus professor of surgery and humanities at the University of Toledo. His column appears every other week in The Blade. Contact him at: aghaji3@icloud.com.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia