The strategic importance of the Pamirs has always drawn the attention of the imperial powers. At the heart of this contest was the rivalry between the British and the Tsarist empires for control of trade routes, resources and balance of power in the region. Their conflict, known as the “Great Game”, reached its climax in the late 19th century. While earlier conquests in Central Asia took place under Russian emperor Alexander II, the incorporation of the Pamirs into Russia occurred later during the reigns of Alexander III and Nicholas II. Afghanistan was within the British sphere of influence. While the western Pamirs, including Darvaz, Rushan and Shughnan, were annexed to the Bukhara Emirate, the Eastern Pamirs (Wakhan and Badakhshan) were drawn into the territories of Afghanistan and China. Following the “Great Game” rivalry, the 1873 Anglo-Russian agreement had left the boundary east of Lake Zarkul (Victoria Lake) vague. Russian advances into the Pamirs in the 1890s created a crisis.

Russia refused to acknowledge Afghan sovereignty over the eastern Pamir, arguing that the region originally belonged to the Bukhara Emirate and therefore passed to Russia when Bukhara became under subjugation. Similar claims had been used to justify Russia’s position in Kulja in Turkmenia. In the summer of 1891, Russia launched an expedition under Colonel Mikhail Yefremovich Ionov (1846-1919).

On June 12, 1891, Col Ionov’s troops, accompanied by officers confronted Afghan forces along the Alichur River. They set up Pamirsky Post by killing Captain Ghulam Haider Khan and seven Afghan soldiers. The Afghans claimed the territory.

They also confronted British officer Captain Francis Younghusband and expelled him along with his troops from Bozai Gumbaz who also signed a treaty to return to Chinese territory. Yavnov threatened the British officer and barred him from returning through Afghan territory to Gilgit because Pamir was claimed by Russia as part of its territory.

The main task of this campaign was to prepare a detailed military survey of the Pamir plateau and eliminate visible presence of Chinese and British authorities. Vrevskii applauded the campaign though they did not advance into Roshan or Shughnan and also withdrew in winters.

Anglo-Brusho War

Russian anxiety increased when Mir of Hunza reported that British forces led by Younghusband and Mortimer Durand arrived in Hunza in late 1891. Petrovski suggested military assistance to Mir to be led by Grombchevskii resulting in formation of a special Pamir Commission, where Prince Lobanov-Rostovskii, Defence Minister Vannovskii, General N.N. Obruchev, and A.N. Kuropatkin discussed the Russia’s Pamir-Hindukush strategy. They declared Aqsu in Murghab valley as a natural frontier with British India. But before the Russian could reach Hunza in aid to the Mir Safdar Khan of Hunza, the British launched Hunza and Nagar campaign also known as the Anglo-Brusho War in 1891.

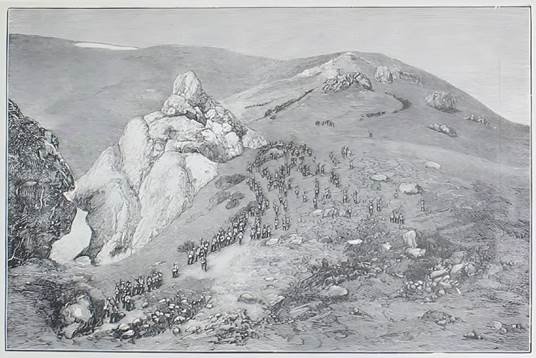

Following the establishment of the Gilgit Agency in 1889, the British moved to consolidate their influence in the region. In 1890, tensions arose when the British conquered Chalt Fort in Nagar. In May 1891, representatives from Nagar and Hunza demanded the British to withdraw from the fort, which they claimed was on their territory. British Raj on December 1, 1891, dispatched over 1,000 troops composed of Gurkhas, Dogras, Kashmiris and Pathans under Colonel Algernon Durand’s command to Hunza and Nagar.

Safdar Ali Khan, the Mir of Hunza warned Durand that any British incursion into Hunza would face resistance. He asserted that he had secured Russian support against the British.

On November 29th, Durand, issued ultimatums to Raja Azur, Khan, the Mir of of Nagar, and Safdar Ali Khan of Hunza citing the British concerns about Russian activities in the Pamirs region. The British commenced the Anglo-Brusho campaign on December 1, 1891 but encountered significant resistance during their advance.

On 23 December 1892, the troops of the British Raj took control of the Baltit Fort and Nagar. The Mir of Nagar was arrested, while the Mir of Hunza chose to flee to Kashgar, and abandon his people. Mir Nazim Khan and Zafar Khan were installed as the new rulers of Hunza and Nagar, respectively.

Russo-Afghan conflicts

Various skirmishes and small battles were fought during 1892 and 93 between Russian and Afghan forces which compelled Russia to develop fortifications in the Pamir e.g., Pamirskih Post by Major V.N. Zaitsev on July 22, 1893.

Russian forces entered to Roshan and Shughnan in 1893 while receiving help requests from the locals as protection from Afghan commanders Shahidullah Khan. Major Zaitsev sent troops under the command of Captain S.P. Vannovskii who faced resistance from Afghans but constant requested from local religious leaders like Mullah Momin Shah, Shukur Mingbashi etc. In late 1893 Russian officers debated whether Roshan and Shughnan fell under Russian influence. Major General M. P. Khoroshkhin argued that the 1872-1873 boundary agreement placed the Panj River as the true frontier, which justified a Russian post at Roshorv. Following these events, Governor Korolkov permitted Zaitsev to restore the post at Roshorv while by 1894 Russian command passed to A.G. Skerskii.

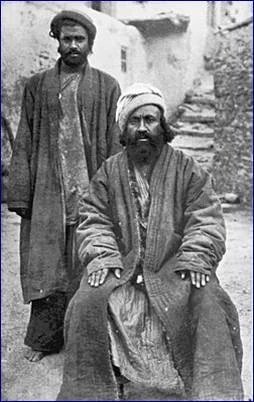

Russian annexation of Roshan, Shughnan and Wakhan relied heavily on framing Afghan rule as oppressive. Russian officers repeatedly cited Afghan cruelty, echoing the language used by local petitioners who described enslavement, heavy taxation and harsh treatment by Afghan governors. The Pamiri preference for Russian rule had several roots. Russian authorities did not prioritise revenue extraction, and Russian rule offered relative protection from Sunni domination, which was particularly important to the Ismaili population. Russian officials promoted religious neutrality and often discouraged proselytising.

Writers such as Bobrinskii argued that the Pamiris viewed the Russians as protectors of their sect in their ongoing struggle with Sunni power. Russian strategists also saw Pamiri Ismailism as useful in a wider geopolitical contest with Islam.

Sayyid Haidar Shah, an Ismaili author, described Afghan rule in Shughnan deceptive and terrorising. He portrayed earlier local rulers as tyrannical and celebrated the arrival of the White Tsar, who brought stability to the region. He acknowledged, however, that Russian protection came with the division of historic Shughnan along the Panj River.

This division marked a major shift in the region’s territorial organisation. Historically, the Panj River had never been a boundary; Wakhan, Shughnan, Roshan and Darvaz extended across both banks. The new frontier, determined without Pamiris’ consent and involvement, fundamentally reshaped the lives of both settled and nomadic populations in the Western Pamirs.

Pamir Agreement and creation of Wakhan Corridor

Russia and Britain resumed negotiations on the frontier conflict. They reached an agreement in 1895 and formed the Pamir Commission, a joint British-Russian expedition with the task to physically demarcate the border. Subsequently they created Wakhan Corridor, a narrow panhandle of Afghan territory as a buffer zone separating the Russian and British empires.

Led by Russian officer Colonel Boris P. Tchaikovsky and the British side by Major General Gerard John Younghusband, with his brother Captain Francis Younghusband and Colonel Algernon Durand as key members who represented their respective empires, the boundary demarcation was aimed at preventing conflict and producing valuable scientific reports on the region’s geology, flora, and fauna. The annexation of the Pamirs represented the final stage in Russia’s consolidation of Central Asia and High Asia.

The Commission mapped the ‘Pamir Knot’, a key point where major mountain ranges converge, starting from Povalo-Shveikovsky peak along the Sarikol in Chinese Pamir, across Zarkul (Victoria) Lake, following the Pamir River watershed down the Panj to Wakhan confluence, then along the Hindu Kush. It effectively placed the northern watershed in Russian domain and the southern in Afghan/British-influenced territory, ending the last major territorial dispute of the “Great Game” in Central Asia. The “Durand Line“ (1893) had fixed Afghanistan’s southern border with British India, and the Pamir Demarcation (1895) fixed its northern border with Russia. This boundary largely persists today as the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan.

The Russo-British Convention of 1907 finalised Afghanistan’s international status. Russia and Great Britain divided their spheres of influence in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet. At the same time, Russia entered the rivalry with Britain, which reshaped European diplomacy before the First World War. The annexation of the Pamirs exemplified the character of Russian expansion in Central Asia. Some regions entered the empire through protectorate agreements or diplomacy. Others such as the Pamirs, were incorporated only after military conflict and imperial rivalry. These conquests followed the logic of great power competition yet imposed deep injustices on local populations whose autonomy declined under Russian rule.

From Revolution to Invasion

Khiva and Bukhara fell to the Bolsheviks in 1920 as a result of 1917’s revolution shattering the old order, that culminated in Basmachi resistance until 1934 in Kokand. The Kazakh famine of 1934 was a result of nationalisation agenda of Stalin that also gave birth to Gorno-Badakhshan, and Pamir being a part of it. This new system also imposed ban on the locals of Pamirs from connecting with their spiritual leader the Aga Khan.

Also read: An illustrated chronicle of the Anglo-Russian contest in Central Asia

. Scholarly journeys through High Asia’s vernacular architecture

Although the flames of WW-II did not reach the region but militarisation was born by the cold war. The Pamir Highway was used as a primary supply line during the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan over the passes once crossed by Timur’s cavalry. The invasion was unsuccessful ending in the collapse of Soviet Union in 1991 but the Tajik civil war of 1992-1997 helped Russian troops stationed in Gorno-Badakhshan guarding the Amu and Panj.

Pamirs: a hotspot in the 21st Century

The Pamirs reemerged as a geopolitical hotspot due to US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. Similarly, China constructed the Pamir Highway from Kashgar to Dushanbe via Kulma Pass in 2004 and ultimately linked Tajikistan to Xinjiang in 2023. According to reports the surveys for Ishkashim-Wakhjir Road started in 2023 to provide ocean access to China bypassing Pakistan. Russia is still maintaining its military presence in Tajikistan; their bases are reinforced in Post-2021 Taliban takeover. They also held military drills with Uzbek and Tajik forces declaring the Amu and Panj Rivers as their red line.

A number of international non-government organisations (INGOs) have been implementing development projects in health, education and telecom sectors in Gorno-Badakhshan and Wakhan since 2001. The Chabahar-Wakhan Corridor is also one of the examples of China’s CPEC alternative. The northern portion of CPEC in Pakistan is as close as a few kilometres to Wakhan corridor.

The lack of resources of Afghanistan is holding Wakhan vulnerable to floods and under developed compelling to seek Chinese investment in infrastructure including mining. The recent Chinese Wakhan push of 2025, Russian military exercises, development of CPEC, and numerous political concerns are risking Pamiri spillover.

The Roof of the World remains contested although tanks are replaced by economic pipelines as the rivalries are evolving. Empires rise and fall, but the wind blows in the Asia’s eternal pivot, the enduring Pamirs.

Dr Zahid Usman is a multi-disciplinary practitioner and educator from Swat Valley. His work as an architect, urban and regional planner, and lighting designer is grounded in spatial planning, large-scale master planning, heritage conservation, infrastructure development, and community development. He is dedicated to developing integrated solutions that balance socio-economic, environmental, and cultural factors. A graduate of the National College of Arts (NCA) Lahore, University College Borås, KTH Stockholm, and International Islamic University Malaysia, Usman now teaches at his alma mater, the NCA, and maintains an active research agenda focused on mountain heritage. He can be reached at: xahidusman@gmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia

5 thoughts on “Anglo-Russian rivalry in Central Asia — the finale at the Pamirs-II”

Dr. Zahid Usman masterfully concludes this two-part series by delivering the promised deep dive into the Pamir campaign, connecting 19th-century imperial machinations to contemporary geopolitical tensions with remarkable clarity. The detailed account of the Anglo-Brusho War, Russo-Afghan conflicts, and the creation of the Wakhan Corridor as a buffer zone demonstrates meticulous research, while the inclusion of military maps and historical photographs enriches the narrative considerably. The author’s architectural and planning background particularly shines in his spatial analysis of how artificial borders disrupted organic territorial patterns, especially noting how the Panj River division severed historically unified communities. The progression from the Great Game through Soviet invasion to China’s Belt and Road initiatives convincingly demonstrates that the Pamirs remain “Asia’s eternal pivot” where economic corridors have replaced military columns but the strategic contest endures. This is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand why Central Asia continues to be a flashpoint in 21st-century great power competition.

Dr.Zahid Usman masterfully concludes this two-part series by delivering the promised deep dive into the Pamir campaign, connecting 19th-century imperial machinations to contemporary geopolitical tensions with remarkable clarity. The detailed account of the Anglo-Brusho War, Russo-Afghan conflicts, and the creation of the Wakhan Corridor as a buffer zone demonstrates meticulous research, while the inclusion of military maps and historical photographs enriches the narrative considerably. The author’s architectural and planning background particularly shines in his spatial analysis of how artificial borders disrupted organic territorial patterns, especially noting how the Panj River division severed historically unified communities. The progression from the Great Game through Soviet invasion to China’s Belt and Road initiatives convincingly demonstrates that the Pamirs remain “Asia’s eternal pivot” where economic corridors have replaced military columns but the strategic contest endures. This is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand why Central Asia continues to be a flashpoint in 21st-century great power competition.

what a wonderful illustration

Dr.Zahid Usman masterfully concludes this two-part series by delivering the promised deep dive into the Pamir campaign, connecting 19th-century imperial machinations to contemporary geopolitical tensions with remarkable clarity. The detailed account of the Anglo-Brusho War, Russo-Afghan conflicts, and the creation of the Wakhan Corridor as a buffer zone demonstrates meticulous research, while the inclusion of military maps and historical photographs enriches the narrative considerably. The author’s architectural and planning background particularly shines in his spatial analysis of how artificial borders disrupted organic territorial patterns, especially noting how the Panj River division severed historically unified communities.

The progression from the Great Game through Soviet invasion to China’s Belt and Road initiatives convincingly demonstrates that the Pamirs remain “Asia’s eternal pivot” where economic corridors have replaced military columns but the strategic contest endures. This is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand why Central Asia continues to be a flashpoint in 21st-century great power competition