Dr Asim Sajjad Akhtar

THIS past Wednesday was Christmas. For me, the occasion is an opportunity to share a sliver of happiness with residents of Islamabad’s Christian katchi abadis with whom I have struggled for dignity and housing rights for years. For most Pakistanis, however, Dec 25 is Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s birthday.

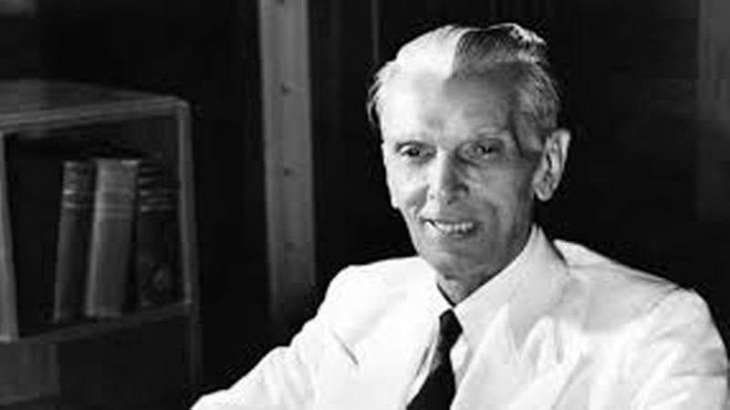

Over the past few years, images of a suit-wearing Jinnah playing with his dog have become popular in the highest echelons of power, particularly establishment circles. I trace the circulation of this image to the aftermath of 9/11, when Gen Pervez Musharraf’s started touting ‘enlightened moderation’ and drew on the ‘liberal Jinnah’ to give legitimacy to his rule.

It was of course under the backdrop of the so-called ‘war on terror’ that Musharraf’s regime attempted to refashion Pakistan’s image. Almost two decades since that chapter of our history began, PR exercises invoking Jinnah and proclaiming ‘Naya Pakistan’ aside, the fundamentals of state policy are effectively unchanged.

We need new forms of mobilisation.

We still cultivate enmity with our immediate neighbours, ‘national security’ trumps all other objectives, and there is a distinct resistance to enshrining principles and institutional imperatives of equal citizenship on religious, ethnic and gender grounds. Junaid Hafeez’s sentencing to death is only the most recent manifestation of how deep the rot goes.

Meanwhile, ambiguity about the Frankenstein that is religious militancy persists. Earlier this month was the fifth anniversary of the APS massacre, which supposedly marked a point of no-return and ‘consensus’ that would take the country forward. Yet ever since, we have experienced the Faizabad dharna, suppression of PTM and many other illustrations of how little has changed.

Today is Dec 27, the day Benazir Bhutto was murdered 12 years ago, a dark episode that took place under Gen Musharraf’s watch. There is nothing to suggest that her killers will be brought to justice soon, or even identified. Indeed, we still don’t know who ordered Liaquat Ali Khan’s assassination! Needless to say, if elected prime ministers can’t get justice, then what of a poor Christian woman living in a katchi abadi, or a child of war in the tribal districts?

Yet Jinnah’s famous inaugural speech to the Constituent Assembly remains a refrain for those in power and those outside of it who seek a progressive and inclusive Pakistan. Jinnah’s secular worldview is certainly worth invoking, but raising the slogan ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’ tell us little about how to actually redress the many structural crises that afflict state and society.

Pakistani society today looks very little like the country carved out from British India. The population then was 30 million; it is 220m now. Agriculture was our economic mainstay; it accounts for barely 15 percent of total output now. Karachi, Lahore and other urban centres were somewhat ordered, colonial bazaars and/or ports; they are now characterised by massive sprawl, inequality and huge carbon footprints. Ethnic tensions have become more acute, militarisation of state and society has reached epic proportions, and Pakistan’s stock in the world is moderate at the best of times. Genuine economic and political independence from powerful states and financial institutions is arguably even more elusive now than when the British had just departed.

Neighbouring India is increasingly a cautionary tale and particularly the fact that legacies of individual statesmen are often trumped by entrenched structures of power. The land of Nehru and Gandhi is now being ripped apart at its seams by Modi and the RSS. Many political biopics argue that Pakistan’s trajectory would have been far more democratic, secular and egalitarian had Jinnah stayed alive as long as Nehru. Quite aside from the utility of such speculations, they tell us nothing about the future society we want to build.

Today Indians of all stripes are struggling to uphold democratic, secular principles that the BJP government is ruthlessly trashing. Protesters across India may be drawing on Nehru and Gandhi’s legacies, but more importantly, they are building class, ethnic, gender, caste and other solidarities in the present that speak of society and state they want to build.

Embattled progressives in Pakistan can also think collectively about how to transform society based on an understanding of all that has changed since Jinnah’s time, whilst challenging the forces of status quo — and the establishment most of all — so as to foment institutional change in our obsolete formal structures of power. Beyond the idea of ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’, we need new forms of mobilisation in the context of a rapidly evolving political field to redress our recurring crises.

Musharraf being held to account for suspending the Constitution provides us an opening, a chance to move beyond lip service and build a Pakistan not in the image of an individual or institution, but for its people. This article was first published in Dawn, Dec 27, 2019

Dr Asim Sajjad teaches at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. He is President of the Awami Workers Party Punjab. he tweets: @asimsajjadA

Dr Asim Sajjad teaches at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. He is President of the Awami Workers Party Punjab. he tweets: @asimsajjadA