A guard tower and barbed wire fences surround an internment facility in the Kunshan Industrial Park which has previously been revealed by leaked documents to be a forced indoctrination camp in Artux in western China’s Xinjiang region. (File photo)

A guard tower and barbed wire fences surround an internment facility in the Kunshan Industrial Park which has previously been revealed by leaked documents to be a forced indoctrination camp in Artux in western China’s Xinjiang region. (File photo)

Leaked data shows the detention of 311 individuals from the Karakax County sent to internment camps for reasons their faith and culture.

High Asia Herald Report

In May 2017, a Uighur man was taken away to a “re-education camp” in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region. As an observant Muslim, the man prayed at home after meals and sometimes attended Friday prayers at his local mosque. The reasons for his forced internment: His wife had covered her face with a veil and the couple had “too many” children. There was never a trial.

The man underwent a “great ideological transformation” in the camp and “realized his mistakes and showed good repentance.” The family’s four boys and two girls back at home all demonstrated “good behaviour.”

In June 2017, however, their mother was sent to prison for six years. She was charged with participating in an “illegal religious activity.”

When a Chinese government mass detention campaign engulfed Memtimin Emer’s native Xinjiang region three years ago, the elderly Uighur imam (religious cleric) was swept up and locked away, along with three of his sons.

Now, a leaked database exposes the main reasons for the detentions of Emer, his three sons, and hundreds of others in their neighborhood: Their religion and their family ties.

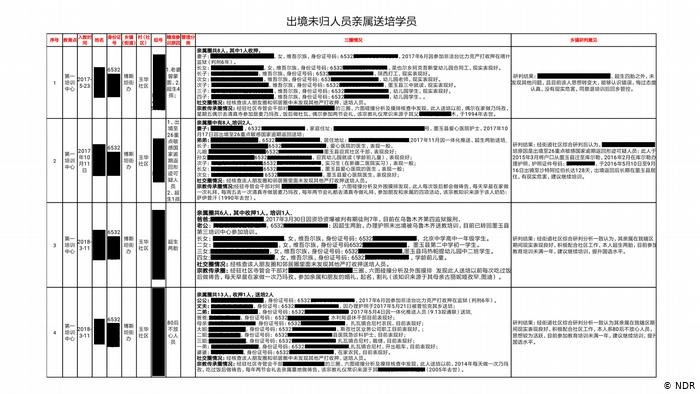

The database – known as the “Karakax list” after the county where it was compiled – comprises 137 pages and exposes in detail the main reasons for the detention of 311 people. It lists information on more than 2,000 of their relatives, neighbours, and friends on the edge of Xinjiang’s Taklamakan desert near Hotan.

Former student Abdullah Muhammad described Emer as one of the most respected imams in the region. He fed the hungry, bought coal for the poor, and treated the sick with free medicine.

But though Emer gave Party-approved sermons, he refused to preach Communist propaganda, Muhammad said, eventually running into trouble with authorities. He was stripped of his position as an imam in 1997.

Though he stopped attending religious gatherings, in 2017 authorities detained Emer, now in his eighties, and sentenced him to prison. The database cites four charges in various entries: “stirring up terrorism”, acting as an unauthorized “wild” imam, following the strict Saudi Wahhabi sect and conducting illegal religious teachings.

Muhammad called the charges false. Emer stopped his preaching, practiced a moderate sect of Islam and never dreamed of hurting others, let alone stirring up “terrorism,” Muhammad said.

Emer’s three sons, too, were all thrown in camps for religious reasons, though they weren’t charged with crimes. It shows their relation to Emer and their religious background caused officials to believe they were too dangerous to let out.

“His family’s religious atmosphere is thick. We recommend he (Emer) continue training,” notes entry for his youngest son, Emer Memtimin.

But it wasn’t just the religious who were detained. Pharmacist Tohti Himit was detained in a camp for having gone multiple times to one of 26 “key”, mostly Muslim countries, the database said. A former employee said Himit was secular, keeping his face well-shaved.

“He wasn’t very pious, he didn’t go to the mosque,” said Habibullah, who declined to give his first name out of fear of retribution against family still in China. “I was shocked by how absurd the reasons for detention were.”

The database says Himit had gone to a mosque three times in 2008, once to attend his grandfather’s funeral. In 2014 he had gone to another province to get a passport and go abroad.

That, the government concluded, showed Himit was “dangerous” and needed to “continue training.”

Emer is now under house arrest due to health issues, Muhammad has heard. It’s unclear where Emer’s sons are. Though deprived of his mosque and his right to teach, Emer had quietly defied the authorities for two decades by staying true to his faith.

This family’s story is similar to hundreds of cases, which are listed in unprecedented detail.

The leak provides information on why people are detained while revealing that Chinese authorities are using high-tech surveillance and sheer manpower to keep track of identities, locations, and habits of individual Uighur Muslims.

The DW or Voice of Germany, German broadcasters NDR and WDR and the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspapwer, spent weeks translating the document and analyzing the data.

https://pauy49167skc

China’s Xinjiang crackdown goes under the microscope

After a suicide bombing struck Xinjiang’s capital city in May 2014, Chinese authorities installed a system of surveillance and mass-detention centres calling them voluntary “Vocational Education Training Centers.” According to estimates, at least 1 million of the roughly 10 million Uighurs living in Xinjiang have disappeared into these centres.

In a confidential report compiled in December 2019 by the German Foreign Office, the centres are referred to as being “effectively re-education camps” with “draconian ideological training courses.”

China claims that “the training centers” are an effective tool in a fight against Islamist terrorism.

However, contrary to the official line from Beijing, there is almost no indication in this latest document leak that Chinese authorities in Xinjiang are targeting potential terrorists.

Although three listed people are suspected to be members of an Islamist organization, above all, the document shows that any expression of Islamic religious piety potentially amounts to a crime.

The document paints a picture of what many international human rights observers fear is a systematic campaign of ethnic profiling and arbitrary imprisonment outside the rule of law.

The list is 137-page data keeps track of minor details, such as videos someone downloaded some six years ago or WeChat messages that were exchanged with friends abroad.

Analysis shows how Uighurs are subjected to draconian methods of tracking and arrest. Facial recognition is carried out with high-tech surveillance cameras. Individual Uighur families are constantly monitored through a network of spies, repeated house visits and collective interrogations.

Verifying the Karakax list

The database shows that cadres compile dossiers on detainees called the “three circles”, encompassing their relatives, community, and religious background.

The detainees and their families are then classified by rigid categories. Households are designated as “trustworthy” or “not trustworthy”. Families have “light” or “heavy” religious atmospheres, and the database keeps count of how many relatives of each detainee are locked in prison or sent to a “training center”.

Officials used these categories to determine how suspicious a person was – even if they hadn’t committed any crimes.

Reasons listed for internment include “minor religious infection,” “disturbs other persons by visiting them without reasons,” “relatives abroad,” or “thinking is hard to grasp.”

The database offers the fullest view yet into how Chinese officials decided who to put into and let out of detention camps, as part of a crackdown that has locked away more than a million ethnic minorities, most of them Muslims.

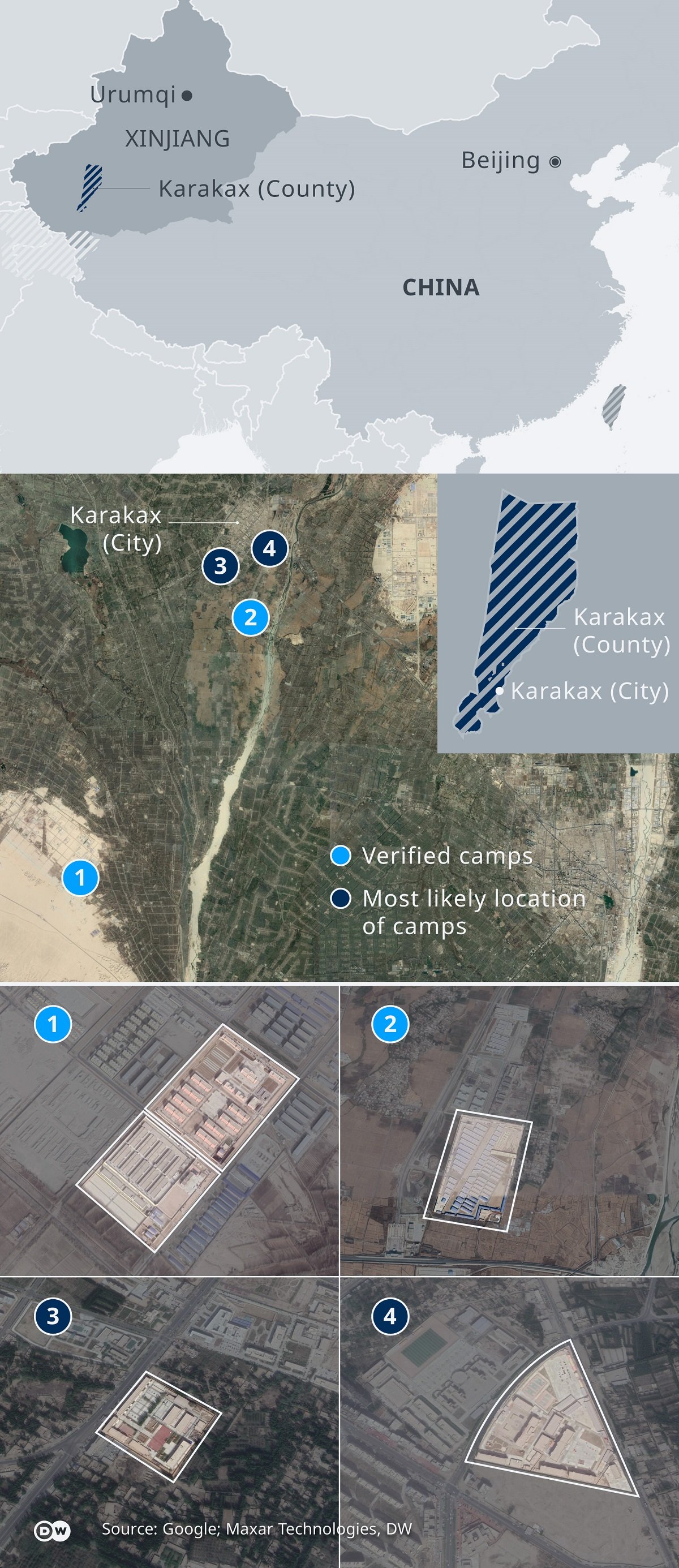

The cases listed are all centered on one region: Karakax County, in Xinjiang’s southwestern Hotan prefecture bordering India and Tibet. There are at least five official “vocational training centres” in Karakax County for a population of fewer than 650,000 people.

The list of detainees mentions four of them. DW was able to verify and locate two of these internment camps using satellite images and government documents. DW was also able to track the likely location of two other camps, using the same methodology.

DW was tipped off about the new document in November 2019 by whistleblower Abduweli Ayup, an exiled Uighur academic currently living in Norway.

Ayup received the PDF spreadsheet from a source whose identity and whereabouts have to remain anonymous for security reasons.

The new leak doesn’t have an official stamp or signature. But its language is similar to other leaks from last year. In November 2019, the “Xinjiang Papers” were published by The New York Times, and the “China Cables” were published by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Both reports revealed the overall scale of Beijing’s stranglehold on the Uighur community in northwestern China. This new document specifically outlines the reasons for internment and provides a closer look at Uighurs’ day-to-day reality of living under systematic surveillance.

DW was able to contact family members of detained Uighurs and consulted experts to verify the information in the document. A woman DW met in Istanbul, Rozinisa Memet Tohti, learned through the list that her youngest sister had also been sent to a camp.

“I was really sad. I couldn’t eat or sleep for many days and nights,” she said.

Adrian Zenz, a leading Xinjiang expert from Germany, and the senior fellow at the conservative think tank “Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation” in Washington has been decoding the new leak since it came to light.

By referencing ID numbers mentioned in the list with publicly available data and other leaked documents, Zenz was able to match hundreds of identities.

“When considering that it contains personal information for over 2,000 people with a considerable degree of complexity, the Karakax List shows a high degree of internal consistency and data validity,” he concluded.

A glimpse of a massive surveillance operation

One case outlined in the new leak is of a man who grew “a long beard,” and whose wife had “covered her face with a veil.”

Based on this profile, Chinese authorities concluded, without much elaboration, that the couple had been “infected with religious and extremist ideas.” The man was sent to a camp. And so was one of his teenage sons.

The case details show that 15 relatives are closely monitored. However, they are described as “behaving nicely,” and all are “actively participating” in daily community service. Therefore, the official recommendation is that the man be sent back to his community for “further surveillance.”

Rian Thum, an expert on China’s Uighur policy at the University of Nottingham, told DW that the monitoring of people’s private lives “is overwhelming” in its level of detail. “I think it is interesting to imagine that these things exist across Xinjiang. The data that is out there must be staggering.”

Forced labour in factories

The fate of Uighurs in the camps also depends on the actions of those on the outside. In some cases, the conduct of family members is used as a direct reference on whether an interned Uighur can be “released.”

About two-thirds of the detainees listed were earmarked for release, only to be kept under continuous surveillance, with their freedom of movement strictly curtailed.

In dozens of cases, DW has found a reference to a system of forced labour in factories.

One such case of prolonged internment at a factory involves a man detained in May 2018 for contacting his brother, who had fled to Turkey.

According to the document, the detainee, therefore “poses a certain level of danger to society.” The recommendation by the “community” is for him to “remain in a factory in the re-education camps.”

‘Illegal’ babies

However, the top cause for the arrest of Uighurs from Karakax County was violating China’s official birth control policy by having too many babies.

According to family planning law, Uighurs and other minorities in urban areas are allowed two children, whereas Uighurs in rural areas are allowed three.

And the numbers clearly show that considerably more men than women were interned for violating this family planning law.

The disparity could indicate that the Chinese government considers Uighur men as the primary threat to its control over Xinjiang.

“I think in terms of Islamophobia, men in general, especially young men, are always the targets and seen as potential terrorists,” Xinjiang expert Darren Byler of the University of Colorado told DW.

“It’s very clear that religious practice is being targeted,” said Byler. “They want to fragment society, to pull the families apart and make them much more vulnerable to retraining and reeducation.”

“My feeling is that the government wants to weaken or diminish the Uighur population as a way of reducing the threat perception.”

DW’s analysis also shows that the Chinese state specifically targets the younger generation. In the document, the term “worrisome person” or “untrustworthy person” is used for people born between 1980 and 2000.

More than 60% of internees are between 20 and 40 years old. “This has major implications for demographics and the birth rate,” said analyst Thum from the University of Nottingham. “If you take a portion — or even the entirety — of a village’s youth, you basically put a pause” on the community’s growth.

‘Criminal’ contacts abroad

Dozens of people listed in the document were arrested for being friends with “a suspicious figure living overseas,” or for going on an Islamic pilgrimage, like the Hajj to Mecca.

In roughly 40 cases, people were also arrested after they applied for a passport.

Chinese authorities have officially deemed 26 countries as “sensitive.” Almost all of them are Muslim-majority, such as Algeria, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia. Any contact with these places is grounds for detention if you are Uighur in Xinjiang.

This list of “sensitive countries” also includes China’s Central Asian neighbours like Kazakhstan, where many Uighurs have family and friends, along with cultural and ethnic ties.

“If the Chinese Communist Party is able to completely eliminate the influence of Islam from all elements of Uighur life, then Uighur culture will certainly be hollowed out,” said Timothy Grose, a Xinjiang scholar at the Rose Hulman Institute of Technology in the US.

This is exemplified by the destruction of mosques and Muslim cemeteries in the region.

The last seems to refer to younger men, according to an analysis of the data by Adrian Zenz, a senior fellow at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington.

“This remarkable document presents the strongest evidence”. The expert on the detention centres who compiled a report on the Karakax list, said he had seen that Beijing “is actively persecuting and punishing normal practices of traditional religious beliefs.”

“It underscores the witch-hunt mindset of the government, and how the government criminalises everything,” said Mr Zenz.

Another set of documents leaked to the New York Times revealed the historical lead-up to the mass detention.

The United Nations estimated in 2019 that 1 million ethnic Uighurs and other mostly Muslim Turkic-speaking indigenous people in Xinjiang were being held in what Beijing describes as “counter-extremism centres” in the province.

The UN also said millions of more people have been forced into internment camps in China.

The most recent date in the document is March 2019. The detainees listed come from Karakax County, a traditional settlement of about 650,000 people where more than 97% of the population are Uighur.

The list was corroborated through interviews with former Karakax residents, Chinese identity verification tools, and other lists and documents seen by the Associated Press.

The database indicates much of the information is collected by teams of cadres stationed at mosques, sent to visit homes and posted in communities. This information is then compiled in a dossier called the “three circles”, encompassing their relatives, community, and religious background.

It showed that Karakax officials also explicitly targeted people for activities that included going abroad, getting a passport, installing foreign software or clicking on a link to a foreign website.

The database shows that the state focused on religion as a reason for detention — not just political extremism, as authorities claim, but ordinary activities such as praying or attending a mosque.

The Xinjiang regional government did not respond to faxes requesting comment. Asked whether Xinjiang is targeting religious people and their families, foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said: “This kind of nonsense is not worth commenting on.”

The Chinese government has said in the past that the detention centres are for voluntary job training and that it does not discriminate based on religion.

China has struggled for decades to control Xinjiang, where the native, predominantly Muslim Uighurs have long resented Beijing’s rule. After militants set off bombs at a train station in Xinjiang’s capital in 2014, President Xi Jinping launched a so-called “People’s War on Terror”, turning Xinjiang into a digital police state.

The document contains a series of assessments for a 65-year-old man, Yusup, according to the BBC. His record shows two daughters who “wore veils and burkas in 2014 and 2015,” a son with Islamic political leanings, and a family that displays “obvious anti-Han sentiment” — a reference to China’s largest ethnicity and the second-largest community in Xinjiang. Yusup’s verdict is “continued training.”

The BBC said many of the family relationships listed in the database show long prison terms for parents or siblings. One man has been sentenced to five years for “having a double-coloured thick beard and organising a religious studies group” while a neighbour is reported to have been given 15 years for “online contact with people overseas,” it said.