In this presentation, Daniyar Kosnazarov analyzes the projection of China’s soft power in Kazakhstan, and draws attention to the barriers that limit Chinese public and cultural diplomacy in Central Asia.

Back in 2014, I was part of a team that established a new government think tank in Astana. At our meeting with president of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev, we introduced our work at the think tank and he sa id a very important thing. I remember this phrase. He said, “Closely examine the Southern neighbor.” He meant China.

id a very important thing. I remember this phrase. He said, “Closely examine the Southern neighbor.” He meant China.

After 2015, when Xi Jinping announced the One Belt One Road Initiative (OBOR), expert discussions in Kazakhstan shifted drastically, from Afghanistan—and U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan—to China. And everyone started discussing the benefits and disadvantages of the One Belt One Road Initiative.

So we also started to look to this topic and we decided to look into soft power, which was a less highlighted topic in Central Asia [at that time]. But before [we discuss that], it is really important to talk about the evolution of the idea itself.

In 2013, when Xi Jinping talked about this initiative for the first time at Nazarbayev University, it was known as the Silk Road Economic Belt. But we have seen that through the years it changed into One Belt One Road and then finally into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Some experts still use these two or three phrases interchangeably. But I think it’s very telling that this shift happened over the course of five years.

In 2013, Xi Jinping was basically testing the waters. And that’s why there was an emphasis on economics, not politics or geopolitics. And as we know, the Eurasian Economic Union had officially started to work in 2015, so it was unclear what kind of reactions to the Belt and Road would come from the Central Asian region and from other important stakeholders in Central Asia. But suddenly, in 2014-2015, Xi Jinping figured out that everyone was pretty much supportive of this idea, and then the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) initiative was launched, so everyone was rushing to try and become a member of this initiative.

Gradually, we saw that Xi Jinping had gained confidence in this initiative and when, after OBOR, a BRI Initiative was proposed, it revealed its international-domestic dynamics. In 2013, Xi Jinping was actually fighting against other political members and there was a harsh anti-corruption campaign and he was not sure how this would end. Back in 2016, ’17 and ’18, particular after the 19th Communist Party Congress, we saw that Xi Jinping had gained absolute power in China. And he started to portray OBOR as his own initiative, as Xi Jinping’s initiative.

If Silk Road has the connotation of a more original project, BRI has a much more global kind, and it shows Xi Jinping’s ambitions to establish a global project.

At the same time, some changes were happening in Russian policies, and this was partially a response to the Chinese One Belt One Road Initiative. So I basically see China and Russia as two powers that are proposing competing futures for the region. When Putin announced his Eurasian Economic Union, there was a sense of hope that Russia could propose a new developmentalist approach for the prosperity of the region. But after Crimea and Western sanctions, the Eurasian Economic Union basically turned into a failure. So that’s why Moscow started to shift its own discourse vis-à-vis the region from the Economic Union to the “security first” approach.

Basically, this approach sends a message to Central Asian leaders that, “If you don’t cooperate with me in the security area, in counter-terrorism, or the fight against ISIS in Syria or Afghanistan, you will not have a future.” But China says, “Let’s establish a common kind of a shared-prosperity, shared-destiny union. And then you will prosper. So let’s build a Silk Road Economic Belt and you will get rich.” So these are the kinds of competing discourses that have been applied by Russia and China to Central Asia.

Actually, Beijing’s developmentalist approach was very timely, since in Central Asia, in particular in Kazakhstan, we were feeling that with the economic crisis and the low oil price, we needed a new vision, new reform. So that’s why China’s vision was very useful. And we see that the elite jumped [onboard with] this idea and President Nazarbayev in 2015 launched his own infrastructure development plan, Nurly Zhol. It was a bandwagon strategy vis-à-vis the Chinese One Belt One Road Initiative.

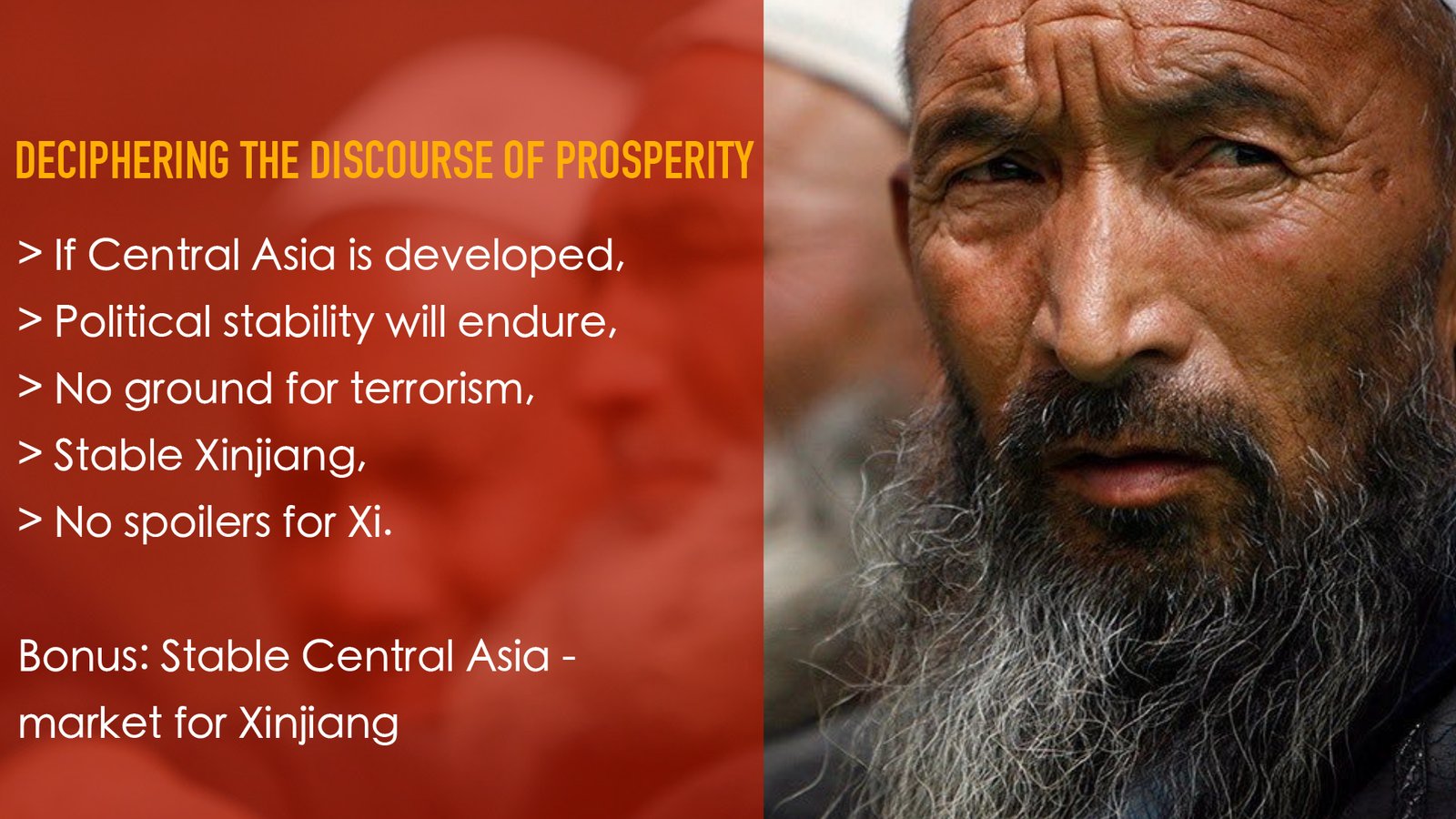

But even though we have Beijing’s developmentalist approach, which emphasizes new liberal policies, like “let’s have free trade, let’s be friends with each other and let’s get rich with each other,” this discourse also has a hidden agenda. So in our work we try to decipher the pathological fears that are being masked by this prosperity discourse.

Actually, the prosperity discourse that China tries to promote in Central Asia and via OBOR hides its own fears about Xinjiang and about stability in Central Asia. And here is a similarity with the Russian discourse of a danger approach, but it is a bit different. It has its own local perspective that China is pursuing.

What China is basically doing is that it wants Central Asia to be economically developed. So that’s why it invests a lot of money in infrastructure and energy in Central Asian states. If Central Asia were developed, China thinks, political stability would endure. So that’s why there would be no ground for terrorism and no one from Central Asia would join ISIS, Al-Qaeda, or some other group. So if there were no ground for terrorism, Xi njiang would be stable and no one would join a separatist movement hand in hand with Uighurs, for example.

njiang would be stable and no one would join a separatist movement hand in hand with Uighurs, for example.

If Xinjiang were stable, there would be no spoilers for Xi Jinping. And the other very good bonus for Xi Jinping is that if Central Asia were stable, it might easily turn into a market for Xinjiang, for example. So these ideas are really hidden behind this OBOR discourse that we are trying to deconstruct.

To sum up, the prosperity discourse is actually one of the important driving forces of Chinese soft power and image and nation-branding in Kazakhstan. So one of the strengths of China is that it has a very engaging and very trusted relationship with the government of Kazakhstan.

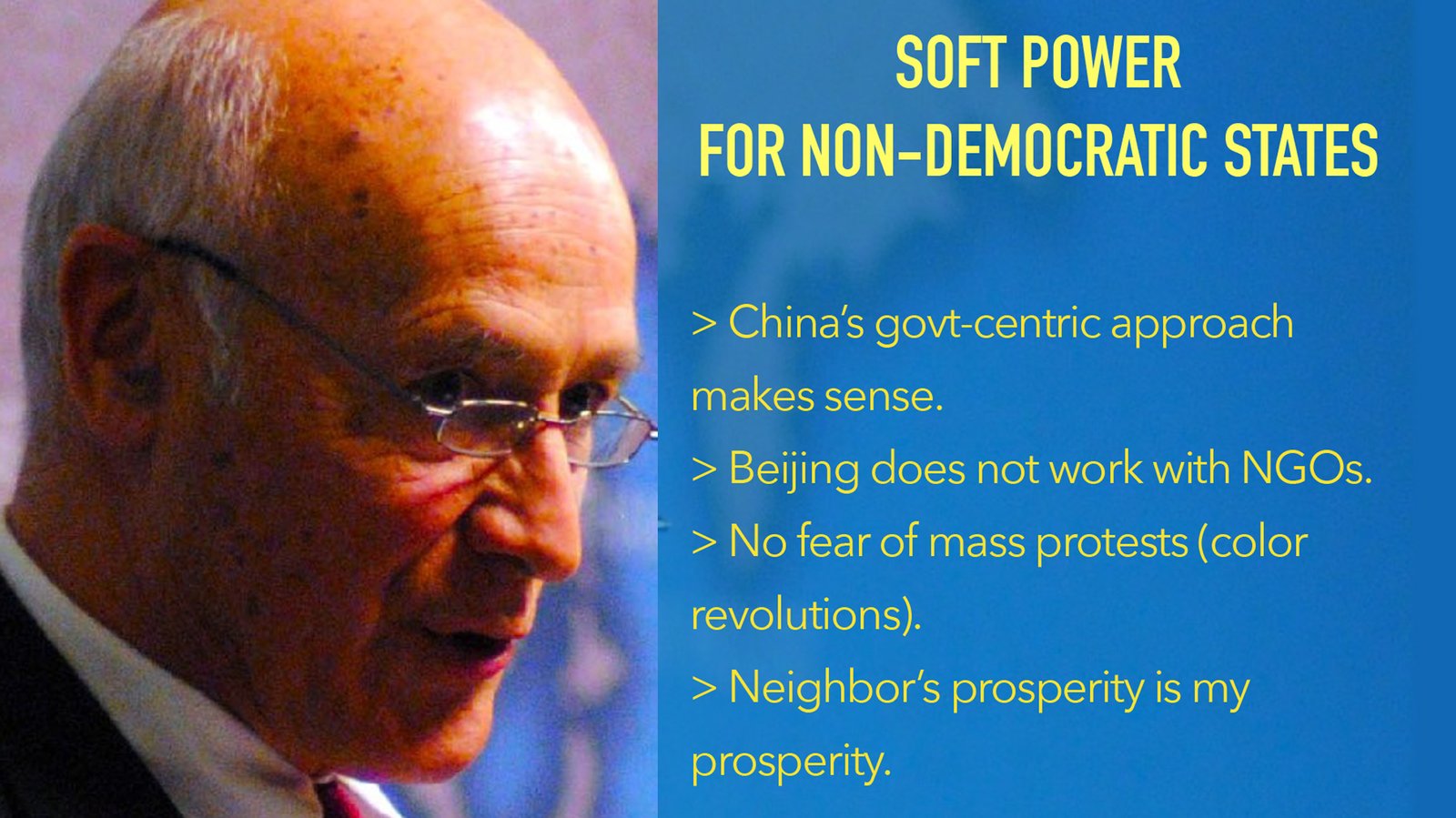

When Joseph Nye presented his idea of soft power, he was basically talking about democratic states and he placed emphasis on civil society. But when we look at China’s interactions with Kazakhstan, we see that these are government-to-government relations. So China is not engaging actively with NGOs and civil society organizations in Kazakhstan. That’s why our Kazakh political elite is very confident that China would not organize some kind of color revolution and destabilize the country, in contrast to Western engagement.

From that perspective, I think we could also see and propose a new soft power concept for non-democratic states. Kazakhstan-China relations prove that government-to-government relations are actually helping China to pursue some ideological and soft power projects.

From that perspective, I think we could also see and propose a new soft power concept for non-democratic states. Kazakhstan-China relations prove that government-to-government relations are actually helping China to pursue some ideological and soft power projects.

I choose one case only, that of the Confucius Institutes.

When China started to engage with Kazakhstan, it actually had several goals in mind. The first goal was to decrease suspicion in a country where Sinophobia was historically strong. The other goal was to increase the resilience of the political regime to economic crises. As these relations started to become much more intensive after 2013, in the period of economic crisis and low oil prices, the Chinese initiative’s loans and credits were actually channeled to some of the companies closely affiliated with Kazakh government elites.

Hu Jintao and Nazarbayev proposed opening Confucius Institutes in July 2005, and we saw the first Confucius Institute opened in December 2007. It was opened at the Eurasian National University. And in February 2009, another government-sponsored university, Al-Farabi University, opened a new Confucius Institute with the cooperation of Lanzhou University. Tellingly, in October 2010, a Confucius Institute was established at Aktobe Pedagogical University. Why Aktobe? Because there is a heavy presence of Chinese energy companies there. Given that they have a presence there, it was also important to improve China’s image in this particular region. But since then, we have seen a spillover from national to private universities. In 2017, Suleyman Demirel University became the first private university to open a Confucius Institute. So the initiative that started back in 2005 led to a spillover to private universities.

Hu Jintao and Nazarbayev proposed opening Confucius Institutes in July 2005, and we saw the first Confucius Institute opened in December 2007. It was opened at the Eurasian National University. And in February 2009, another government-sponsored university, Al-Farabi University, opened a new Confucius Institute with the cooperation of Lanzhou University. Tellingly, in October 2010, a Confucius Institute was established at Aktobe Pedagogical University. Why Aktobe? Because there is a heavy presence of Chinese energy companies there. Given that they have a presence there, it was also important to improve China’s image in this particular region. But since then, we have seen a spillover from national to private universities. In 2017, Suleyman Demirel University became the first private university to open a Confucius Institute. So the initiative that started back in 2005 led to a spillover to private universities.

Talking about the challenges to the prosperity discourse and China’s soft power in Kazakhstan, we should remember that there were massive land reform protests in many cities of Kazakhstan. So I think the ultimate challenge for China in the medium-term and longer-term perspective is that the Kazakh population is becoming the dominant ethnic group. As we can see, there is ethnic return migration— Kazakhs from different countries (China, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan) are flowing back to Kazakhstan—and we see the mass exodus of many ethnic minorities from Kazakhstan.

There is a dramatic demographic shift under way in Kazakhstan and Kazakhstan is becoming a mono-ethnic state. And as we see, ethnic Kazakhs are the most vocal critics of government policies. Kazakhs are the most important group that is very critical and that is becoming nationalistic. The protests of 2016 show that xenophobia will grow—and it will affect China as well, since China is becoming very visible in many regions of Kazakhstan. And the general discourse is that, “They will take our jobs, they will marry our women, and they will take our lands …”

Also see video: https://youtu.be/QBozTagktL8

This is the edited transcription of a presentation made on November 14, 2018 by Daniyar Kosnazarov and published in the Voices on Central Asia on Januray 15, 2019.

Daniyar Kosnazarov is a visiting fellow at The George Washington University. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of Steppe, an independent digital media outlet in Kazakhstan. He has experience both in the government and in private think tanks in Kazakhstan, and previously worked as Chair of the Department of Strategic Analysis at Narxoz University, evaluating strategy implementation.

Daniyar Kosnazarov is a visiting fellow at The George Washington University. He is also the Editor-in-Chief of Steppe, an independent digital media outlet in Kazakhstan. He has experience both in the government and in private think tanks in Kazakhstan, and previously worked as Chair of the Department of Strategic Analysis at Narxoz University, evaluating strategy implementation.