The artist took photography as seriously as painting

By Celia Stahr

Frida Kahlo, like her father, used photographic images—often with written words accompanying them—much the way she used painted images: as a repository for her profound and sincere emotions and ideas. When Frida was in San Francisco she continued this photographic tradition. The calculated image she projected for the camera was intended to shake things up, and the photos she sent her parents, sometimes with inscriptions, were meant to reaffirm her place within the family. But the photographs of Frida that stand out from her stay in San Francisco were taken by two professional photographers, Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham.

The first photoshoot occurred on a cool December day, a few weeks after Frida had arrived in San Francisco. She stepped down into Stack’s sculpture studio, where Diego Rivera and Edward were catching up on the news of each other’s lives since the heady days of the 1920s when Edward had lived with Tina Modotti in Mexico. Frida had never met Edward because by the time she’d joined Tina’s salon Edward had returned to the United States, though she would have heard about him from Tina.

Tina and Edward had had a complicated romantic relationship that paired a married photographer with his muse and model, a woman who would go on to create a life for herself as a photographer and political agitator. Edward wasn’t as interested as Tina in the life of an activist, and he certainly didn’t want his photographs to carry political messages.

He was content to focus on images of nature, nude women in natural settings, close-ups of vegetables and people’s faces. He became a leading figure in the fine art of “straight” photography—photos with a crisp, clear focus. Edward eventually settled in the Carmel coastal area of California but remained close to San Francisco–based photographers such as Imogen Cunningham and Ansel Adams.

In 1930 Edward made the short trip from Carmel to San Francisco to see Diego and meet Diego’s new wife. When he saw Frida in her ethnic attire, her dark hair pulled back to showcase her striking features, he was transfixed. “She is quite beautiful,” he wrote, and “shows little of her father’s German blood.” He knew a good photographic subject when he saw one and began taking some black-and-white pictures of her. In a candid shot, Frida steals a glance at the camera lens, with a slight smile that hints of a coquettish yet mischievous woman, while Diego’s eyes are fixed on Frida, who stands next to him in a three-quarter pose.

All eyes are on Frida; she’s probably just made one of her witty comments, employing vulgar language to punctuate a point. Whatever she’s said, it has evidently caught Diego’s attention, because he turns his head toward her and smiles. She wears a full-length dress, a European narrow silk shawl with fringe, three large jadeite Aztec beaded necklaces, and dangling metal earrings with a floral design.

When Frida walked with Diego and Edward to an Italian restaurant in the Montgomery Street neighborhood, she caught the eye of locals who stopped to admire her outfit—huaraches peeking out from under a long, full skirt, a deep purple, mauve, and green striped silk shawl with dangling amber-colored fringe wrapped around her shoulders. Even in this bohemian section of San Francisco, the sight of this unknown Mexican woman created “excitement,” as Edward marveled.

The rebozos Frida wore conveyed her allegiance to the indigenous women throughout the various regions of Mexico.

But Edward also commented on Frida’s strength, something he captured in another photo taken before the threesome had departed for the restaurant. A solo Frida sits with her hands resting in her lap, looking off to the left as if she’s caught in thought. This photo showcases the dark striped rebozo draping her upper body, with its thick folds highlighting the contrast of light and shadow, drawing the eye to its beauty. The shawl frames the three strands of large, heavy jadeite Aztec beads, emphasizing Frida’s strength, both literal (her strong neck and back muscles) and political (her alliance with Aztec culture). Even if San Franciscans didn’t understand the political level, the photo makes clear that Frida is a thoughtful, strong woman who is aligned with indigenous women.

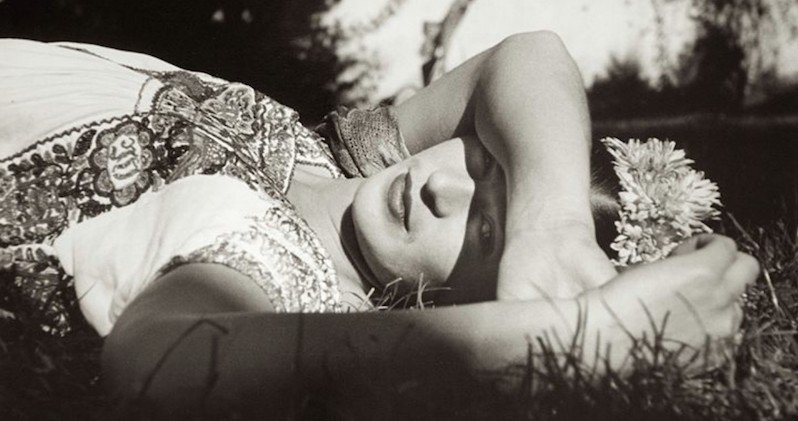

Edward must have liked this contemplative pose because he took another photograph of a pensive Frida. In this photo, however, he moved in closer to show her from the chest up. Her head is angled to the left and she looks down, creating an intimate moment as if we are able to peer into the internal workings of Frida’s mind. Her downcast eyes make it easy for us to feel comfortable staring at her because she doesn’t look back.

And there is much to gaze upon: Frida’s features (thick eyebrows, long eyelashes, high cheekbones, wide nose, prominent lips) and the same heavy, three-stranded jadeite necklaces and gold metal earrings. Both pieces of jewelry display pride in her indigenous heritage: the earrings link Frida to the state of Oaxaca, the region where her mother grew up, and the necklaces connect her to the fierce Aztec warriors. As Edward noted, Frida’s German side isn’t obvious.

Frida was as meticulous about what she wore as she was about what she painted. She made her choices based upon aesthetics and symbolic meaning. It’s therefore of note that in this third photo, her shoulders are covered by a different rebozo than in the previous two shots. A Mexican woman’s rebozo conveys different messages depending upon its material, the area where it’s from, and the way it’s worn. It can be draped over the head to enter a place of worship, to protect from the sun and wind, or to mourn the loss of a loved one. It can be wrapped tightly around the body to indicate the unmarried status or it can be used to carry a small child.

In the first two photographs, Frida’s rebozo is made of silk, and its design derives from European shawls; both these aspects connect her to the upper-middle class. The shawl she wears in the third photo is probably made of rayon; a similar one from Guanajuato was found in Frida’s closet after her death. Women in rural areas typically wore rayon shawls with a mottled pattern of white specks.

The rebozos Frida wore conveyed her allegiance to the indigenous women throughout the various regions of Mexico. They became an important symbol of her identity while in the United States. Although the rebozos differ in Edward’s photos, what remains the same is the focus on Frida as a striking, thoughtful, indigenous-looking woman. Beauty and intelligence were traits not commonly ascribed to Indian women, so by combining these various traits, Frida was creating a new persona of the indigenous Mexican woman, one she felt good about, informing her mother: “I had some wonderful pictures taken of me, as soon as I have copies I will send them to you.” This article was first published in LiteraryHub.

![]() Celia Stahr is a professor at the University of San Francisco, where she specializes in modern American and contemporary art with an emphasis on feminist art and gender studies, as well as African and multicultural art. She holds a Doctorate of Philosophy from the University of Iowa and lives in the Bay area.

Celia Stahr is a professor at the University of San Francisco, where she specializes in modern American and contemporary art with an emphasis on feminist art and gender studies, as well as African and multicultural art. She holds a Doctorate of Philosophy from the University of Iowa and lives in the Bay area.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia