A research paper published recently by Mountain Societies Research Institute (MSRI), University of Central Asia, highlights the social, economic, and environmental impacts of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which follows ancient Silk Road corridors.

Even short-term economic benefits promised by China carry huge risks of debt dependency, forfeiture of mining and land rights, natural resource exploitation, and disruption of traditional land use, among other concerns.

Roy C. Sidle

In the wake of the lucrative investment treaty between the European Union and China unveiled at the close of 2020, concerns raised in a recent article I published in the journal Sustainability become all the more relevant.

While the EU Trade Commissioner has lauded this treaty as the most ambitious outcome that China has ever agreed with a third country in terms of access, fair competition, and sustainable development, many have criticized China’s ultimate commitment to the terms of this agreement.

The timing of the treaty coinciding with a lame-duck US President who was more obsessed with overturning his recent election defeat and inciting discontent rather than playing an active role in international relations is likely no coincidence.

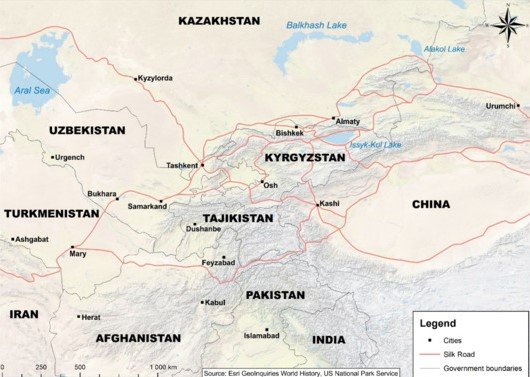

An important, but heretofore little discussed, aspect is the role that the multi-trillion-dollar Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will play. To better understand this connection with the recent trade treaty, it is necessary to recognize the key linkage of the planned BRI infrastructure development through Central Asia, coinciding with the locations of the ancient Silk Road.

The nostalgic trading and information exchanges along these routes dating back to the 1st Century BC is contrasted with the military aggression of the Han Dynasty and the spread of the Black Death plague from China into Europe in the 14th Century along these same corridors.

After a long period of quiescence, as other trading routes emerged, China now plans extensive expansion of roads, railways, and pipelines through the formidable Tien Shan and Pamir mountains of Central Asia.

While the poorer Central Asian nations have largely embraced the BRI, even the short-term economic benefits promised by China carry huge risks of debt dependency, forfeiture of mining and land rights, depletion of natural resources, disruption of traditional land use, overreliance on cheap Chinese products, and few local employment opportunities in Chinese-based projects. All of these issues have been overlooked by EU politicians, while, at the same time, the EU supports certain environmental initiatives in the region.

An important issue that has been separately discussed, but not linked to this China-EU treaty, is China’s treatment of Muslim Uyghur minorities in Xinjiang, many of which reside in so-called ‘re-education’ or forced labour camps near the borders of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan.

Products from the ‘cotton supply chain’ originating in these camps have been pouring through Central Asia and this trade treaty will undoubtedly perpetuate the abuses against Uyghurs as long as China prevents outside investigation into these camps. Related to these civil rights abuses is China’s requirement of Central Asian nations to abide by the One China policy, including not criticizing policies and treatment of Uyghurs and Tibetans, as well as allowing extensive Chinese military exercises on Central Asian lands.

Another social issue that is being ignored related to BRI development and EU trade is the increased exposure of remote villagers to communicable diseases as road development in these regions expands due to natural resource exploitation and shipment of Chinese goods. Such isolated people are at high risk as evidenced by the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Even less attention has focused on the environmental consequences of road expansion through mountainous Central Asia, particularly Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and neighbouring north Afghanistan. China has deliberately been developing cosy relationships with these nations through loans, scholarships, and reduced shipping expenses, but expects governments to turn a blind eye to the paucity of environmental provisions associated with road development along with social and economic deficiencies.

Very little attention to BRI development on the environment has been reported, and this has mostly focused on air quality, habitat and biodiversity loss, and local pollution effects.

Map of the ancient routes of the Great Silk Road through the Central Asian region with countries indicated in their current borders. Source: Esri Geo enquiries World History, US National Park Service.

A virtually unnoticed aspect of road development in this region with huge consequences for travellers, property, indigenous communities, and the environment is the increased incidence and impacts of natural hazards. While landslides, debris flows, snow avalanches, floods, rockfall, and glacial hazards abound in the Tien Shan and Pamirs, mountain road development greatly increases the occurrence of these hazards as well as the risk to humans and property.

Given the poor development of mountain roads in Yunnan Province, China, one cannot anticipate a better outcome in Central Asia where the terrain is more formidable. Landslide erosion along newly developed mountain roads within UNESCO’s designated “Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas” in Yunnan is the highest ever reported worldwide. Road networks connected to streams can also enhance flooding if not properly designed. The legacies of poorly planned and developed mountain roads last decades after they are constructed exposing people, properties, and waters to destruction and degradation.

The social, economic, and environmental impacts of the BRI transcend the impacts imposed by the recent China-EU investment treaty. Nevertheless, the legacies of past social and economic issues along these ancient Silk Road corridors, together with the current environmental, human rights, disease transmission, and sustainable economic concerns, need to be considered.

It is not reasonable to expect poor Central Asian nations to embrace sustainable development decisions when large intergovernmental actors like the EU ignore these potential impacts on poor nations to improve their own economies. Governments in these post-Soviet countries should be encouraged to secure more sustainable outcomes from the BRI, including focusing on a systematic approach that examines all externalities and potential impacts.

I concluded my recent paper entitled “Dark Clouds over the Silk Road: Challenges Facing Mountain Environments in Central Asia” with a line from Paul McCartney’s ballad:

“The Long and Winding Road

— The wild and windy night,

That the rain washed away,

Has left a pool of tears

Crying for the day”.

This article was originally published in the journal Sustainability We are republishing it with the permission of the author.

Roy C. Sidle is the Director of the Mountain Societies Research Institute and Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Central Asia, Khorog, Tajikistan; he also holds a Distinguished Professorship with Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology and has published extensively on natural hazards worldwide. Formerly, he was Professor at Kyoto University from 2002 to 2008

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia