Amir Hussain

It might have been a chilly Saturday with clouds of victory hovering over the defence lines of Gilgit Scouts on November 1, 1947. It was a historic day when a legion of local military men of Gilgit Scouts revolted against the Dogra ruler of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). These men in uniform overthrew the regime of Maharaja Hari Singh of state of J&K when Brigadier Ghansara Singh as Governor of Gilgit Agency surrendered to local mutineers of Gilgit Scouts. At the time of the revolt, the British military officer William Alexander Brown was the commander of Gilgit Scouts who fully supported the local revolt against the Dogra rule.

If one reads the historical accounts including Major Brown’s memoir, ‘The Gilgit Rebellion it becomes clear that Operation Datta Khel was secretly planned by Colonel Roger Bacon, Major William Brown and Captain Mathieson to oust Ghansara Singh.

Unlike other parts of J&K like Ponch and Srinagar, there were no communal riots in Gilgit Agency and one can hardly find any evidence of popular uprisings against the regime of Maharaja Hari Singh. There was of course resentment against the repressive Dogra rule among the local rajas but before it could transform into a popular movement the Dogra regime in Gilgit was toppled through military revolt. It took hardly two days for Major Brown to hoist Pakistani flag in Gilgit and on November 16, 1947, Pakistan sent Sardar Muhammad Alam Khan, a civil servant from Peshawar, as its political agent for Gilgit Agency.

Gilgit passed into the hands of Maharaja Gulab Singh, the first ruler of the state of J&K, after the Treaty of Amritsar in 1846, Col Nathe Shah, who was deployed in Gilgit on behalf of the Sikh Court in Lahore retained his position under Gulab Singh as his subordinate after the defeat of Sikh Empire in the Anglo-Sikh war of March 1846.

The Treaty of Amritsar signed between Maharaja Gulab Singh and the British Empire gave the Maharaja free hand to annex the northern parts of his kingdom. This northward expansion of the kingdom was strategically planned by the British rulers to create a buffer between Russia and the British Empire as part of the geostrategic politics of the Great Game era.

The strategy was to keep the Russian Empire away as far as possible, by creating a vast buffer zone in the rugged mountains of the northern areas. British Indian rulers also facilitated the Maharaja of J&K to bring the small states of Chitral and Yasin under his control in 1877.

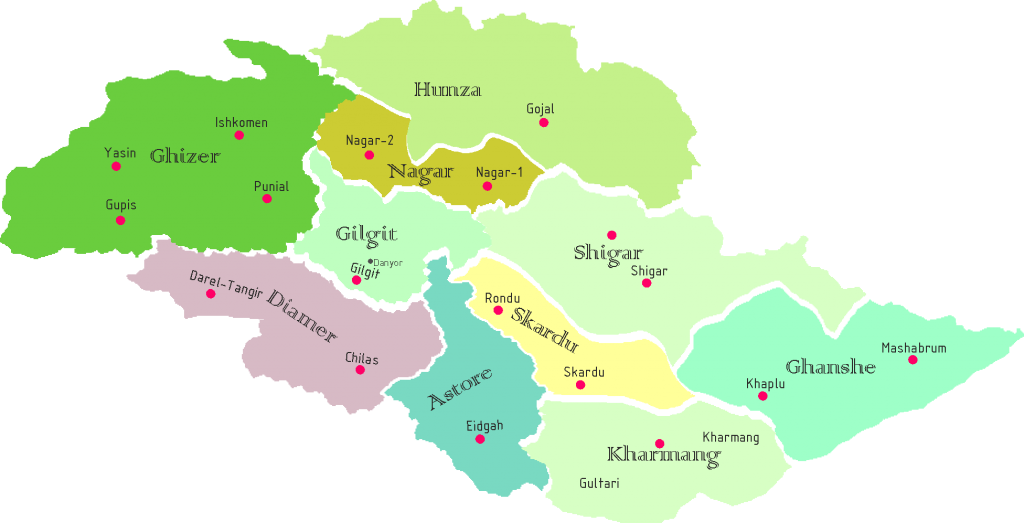

In 1878, the Mehtar (ruler) of Chitral accepted the suzerainty of the Maharaja of J&K and so was the case with the principalities of Hunza, Nager, Punyal and Gupis. However, the areas of Diamar including the valleys of Darel and Tangir continued to function as acephalous societies without any external control and they remained autonomous throughout the colonial period.

From this historical standpoint, Gilgit Wazarat remained an integral part of the state of J&K till November 1, 1947, while the local small states continued to function as vassal states under the suzerainty of the Dogras of J&K. There is also another dimension of this historical debate that the state of J&K itself was an artificial entity created by the British Empire to meet its strategic objectives during the Great Game on the eastern borders.

The word liberation is loosely used by many people to describe the Gilgit revolt of November 1, 1947, but it was a local revolt in the barracks of Gilgit Scouts sans a popular political movement. This is not to suggest that the rule of Maharaja was benevolent to get away with popular uprisings. It was rather a carefully executed plan to manage a seamless transition of rulers within the larger scheme of the emerging hostilities of the Cold War safeguarding the Western interests in the region.

The first priority of outgoing British colonizers was to block Indian physical access to the Soviet Union and Afghanistan because of India’s inclination towards the Socialist bloc. This becomes evident from the haste with which Major Brown hoisted Pakistani flag in Gilgit and persuaded local mutineers to accede to Pakistan on the very next day of the successful revolt. Lord Mountbatten (the first governor-general of India), Jawaharlal Nehru (the first prime minister of India and Vallabh Bhai Patel (first deputy prime minister of India) seemed to be on the same page in decoupling the Gilgit-Baltistan (GB) from J&K dispute.

This is also evident from the writings of V.P Menon and correspondence between Nehru and Patel in the aftermath of the partition of the Subcontinent. There was an understanding between Congress leadership and British rulers about the decoupling of GB from the state of J&K but this understanding was governed by many ifs and buts. It was, therefore, important for the British rulers to ensure that this decoupling takes place during the time of Lord Mountbatten as the first Governor-General of India.

From the beginning, there were apprehensions in the minds of political strategists in the British Empire about the capability of the state of J&K to act as a colonial outpost on the eastern borders of the Empire. These apprehensions became more pronounced when the British took over the control of Gilgit Agency through a 60 years’ lease from Maharaja of J&K in 1935. The British government and the princely state of J&K continued to work in unison on the eastern borders where the latter was only a vassal state to protect the political and economic interests of the British Empire.

The state of J&K was an arbitrary political amalgamation of different cultures and people from Jammu to Ladakh and from GB to Srinagar as a geostrategic area to serve the colonial interests of Russian containment. Despite a hundred years of their political association, the people of J&K and GB could not develop a common political aspiration.

People of GB believe that the Dogra raj was a forced occupation over their territory very much like the colonial rule of the British Empire in India. Therefore, the ongoing national debate about the change in the political status of GB must be seen in this larger historical perspective of colonialism and international politics.

Despite the horrendous colonial experience under the Dogra rule the people of GB still believe that if Pakistan cannot bring this region under its constitutional ambit, it should at least grant a special package to ensure protection of all political, legal and economic rights of the people.

This should entail representation in the national assembly and senate by amending articles 51, 59, 257 and 258 of the constitution. It should involve dissolving the GB Council and transferring the functions of the ministry of GB and Kashmir affairs to the local legislative assembly.

Thus the proposed framework of the provisional constitutional province must entail a fully empowered local legislative assembly with a lean bureaucratic structure, an independent judiciary, representation in all constitutional bodies and eco-friendly investment under CPEC projects.

Despite the decades of legal and political exclusion the people of GB have always shown allegiance to the state of Pakistan, it is now for Pakistan to act in reciprocity.

Aamir Hussain is a social development and policy adviser, and a freelance columnist based in Islamabad. Email: ahnihal@yahoo.com, Twitter: @AmirHussain76