There was an uncanny similarity between the lives of Pushkin and Manto, writes Raza Naeem. Both were largely unrecognised in their own lifetimes, despite believing unapologetically in their own greatness, achieving immortality only after death

Herald Report

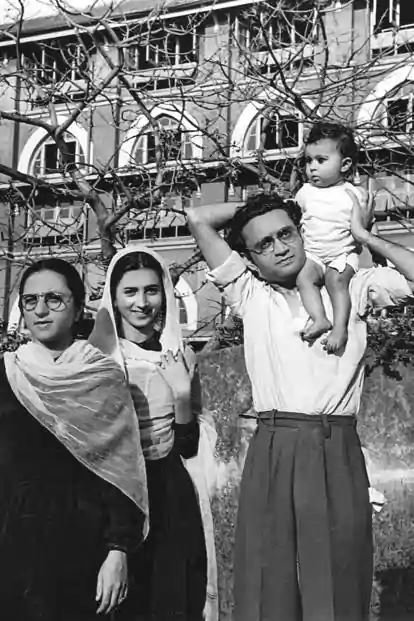

On May 11, Google celebrated the 108th birthday of renowned short story writer Saadat Hasan Manto with a doodle. Saadat Hasan Manto was born to a middle-class family in Indian Punjab’s Ludhiana city on May 11, 1912. He migrated to Pakistan after 1947 Partition of the Indian Subcontinent.

Manto in his early 20s studied the classics of Western writers and learned the art of short-story writing. He translated Russian, French and English short stories into Urdu. He would write an entire story in one sitting with very few corrections, His favourite subjects were those of taboos and stories of social injustice, hypocrisy, and exploitation of women.

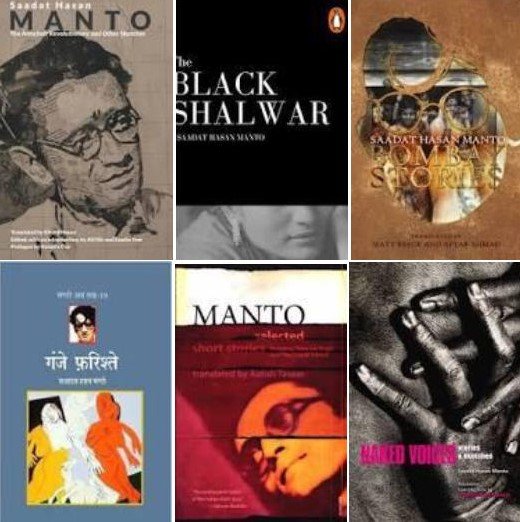

Manto had penned 22 collections of short stories, a novel, five series of radio plays, three collections of essays and two collections of personal sketches which were translated in different languages.

According to Waseem Altaf, he was deeply influenced by the writings of Latin American writer Victor Hugo, Oscar Wilde, Russian fiction writers and poets Pushkin, Chekov and Gorky. He had leftist leanings initially, yet during later years, he was greatly fascinated by the dynamics of the human psyche, which finally turned into scathing satire, and a kind of black comedy, after the bloody events of Partition, the financial crises he faced, and the treatment meted out to him, by the state and the society at large.

Manto, like D.H Lawrence, focused on tabooed subjects and was often accused of promoting vulgarity and pornography. He, however, rubbished it and said that he only “exposed the truth.” And the fact remains that Manto was brutally honest in his stories and in real life which made him not a very likable person for others.

In Pakistan, he was tried thrice for obscenity in his writings. Disheartened and financially broken, he expired at the age of 42. In 2005, on his fiftieth death anniversary, the Government of Pakistan issued a commemorative postage stamp. On Aug 14, 2012, Manto was awarded Nishan-e-Imtiaz, the highest civil award by the Government of Pakistan; 57 years after his death.

Analysing the writings and life of Pushkin and Manto, Raza Naeem, who is an award-winning translator and expert on Manto, wrotes in Naya Daur online news magazine:

“Russia’s national poet, Alexander Pushkin, the equivalent of the likes of Tagore, Iqbal, Goethe, Dante, Confucius, Shakespeare and Cervantes. To mark this momentous occasion, I am presenting here an original translation from Urdu of the great Saadat Hasan Manto’s tribute to Pushkin, published in the ‘Russian Number’ of the Urdu journal Humayun issued from Lahore in May 1935. This is a significant date since, at the time of writing, Manto was a member of the Progressive Writers Association, and had embarked on his literary journey, initially as a translator, and yet to write the literary masterpieces for which he was to eventually become famous and notorious; as well as the fact this was arguably the first and one of the most significant writings on Pushkin at the time in South Asia. What is also interesting to note for the contemporary reader here are the uncanny similarities between the lives of both the writer and subject: for both Pushkin and Manto were largely unrecognised in their own lifetimes, despite believing unapologetically in their own greatness, achieving immortality only after death; both had their run-ins with the law for their reformist tendencies, Manto more so; both wrote masterful short-stories, and both died young. The beginning of modern Russian literature begins with the 19th Century. The atmosphere of that time was flourishing with exhaustive ideas. The pulse of the people was beating with the ‘Corsican fable’ (the invasion of Napoleon). A feeling of awakening was turning within the bosom of the nation and the doors of a new world were opened with some pleasant morning breeze.

When such are the conditions all around, what sort of melodies could rise from a young man’s harp of thought?

A song of a new life!

A song of awakening!

If the English Renaissance appeared in the form of allegory-writing, then the bud of the literature of the red land bloomed in the shape of lyrical poetry. If England gave birth to a great allegoriser like Shakespeare, then the dead land of Russia produced a magic-making lyrical poet named Pushkin whose exhilarating songs continued giving life to the literary ambience for a long time.

Alexander Pushkin was born on 6 June 1799 in Moscow and departed from this world by reaching the age of the fire-breathing poet Byron. Though this young poet was fated to see very few springs of his age, he achieved worldwide fame in this period.

Pushkin’s paternal grandfather was of Arab origin, whom Peter the Great had bought for a bottle of wine in Constantinople and who married a German woman after some time.

The inheritor of such a strange sort of tradition took his early education from French teachers and a Russian maid, and within a short time, meaning at the age of 18, earned a degree of higher education from a good university. He did not prove an intelligent student during the period of education, but even his verses from that time are witness to his greatness.

After finishing his education, he wandered in different places for 2-3 years. Pushkin was naturally an independent-minded man, so he could not save himself from the wrath of the government and was exiled for some time. During this time, the black and white of his thought kept circling in different fields.

In 1826, he resided in Petersburg on his return where his young female admirers, as well as the censors of the authorities, surrounded him.

At the age of 32, he married an adorable 16-year-old girl, who was the epitome of beauty. The poet began to work with great diligence and devotion to provide for the requirements of this beauty – just so that his beloved life partner could get a prominent position in the social circle. So these financial problems and domestic worries indeed affected the health of the poet adversely.

Pushkin is counted among the likes of Dante, Shakespeare and Goethe, though a few critics indicate a few defects too in his verse. But everyone agrees that he is the very first and undoubtedly the greatest national poet and thinker of the red nation. Pushkin himself recognised his greatness. He writes in a poem of his:

‘No! I cannot die

My spirit is alive, though my body has changed into a fistful of earth

I am alive, famous and will remain so.

Till there is a poet breathing with life under this sky

My name will be on every tongue high and low

Nation after nation will be captivated by my love

Because my songs have awakened delicate emotions within them

And pleaded for mercy for the fallen!!’

Pushkin’s verses resemble the fiery thoughts of Byron on a few occasions. In his songs, he often gives a message to the Russian nation to awaken from dreams and know their responsibilities.

In a poem, Pushkin addresses the nation, provoking their sense of honour:

‘Comfort-loving nations!

If the instrument of greatness cannot awaken you,

Then go! Live on grass!

Can a flock of sheep claim freedom?

They are fated to be shorn or slaughtered!

What else did their ancestors give their generations as an inheritance

Except for the decayed life of slavery?’

Pushkin tried free verse, influenced by Shakespeare, and penned an allegory. The subject of this allegory is the tormented air of Russia. Though the competent author has exhibited fine artistry in narrating the psychology of his characters, even then it can only be said to be an allegorical poem rather than a proper allegory. It is steeped in poesy from one end to the other, from which the result can be extracted that Pushkin was not a great allegoriser but a genuinely great poet.

Every song of Pushkin is itself worthy of a lengthy discussion. However, suffice it to say that every single verse of his is the beautiful ornament of the bride of the poetic kingdom.

His verses are untranslatable owing to their great beauty; because while transferring them into a foreign language, the apprehension is lest the rough hands of the translator mutilate their true shape (ref Russian Literature by Jahko Lavrin). However, in my humble opinion, a translation of some verses from a song of his could be this:

‘I loved you

The embers of that love indeed

Still remain in the ashes of my love

I confess to it!

But do not be distressed with this thought

I do not want to sadden you again!

I have adorably loved you!

And now pray with my heart

Someone else loves you as I did!’

Pushkin’s magic is natural. He narrates an ordinary thing in such a poetic and ecstatic style which is solely his own – this magical creative power was the philosopher’s stone which Pushkin invented, granting every verse of his a brilliance of pure gold.

Pushkin’s verse is totally uncorrupted by affectation. His style of reciting poetry makes this reality clear that all his verses arrive naturally. Actually, in Pushkin’s hands, the creative zenith was a toy with which he played for a long time.

All his work, meaning poetic narratives, songs and ghazals consist of not a single word which could indicate any artificiality or affectation. Many a revolution may come in time, a hundred new poets be born, but Pushkin’s greatness is eternal and will remain eternal.

Pushkin has also turned his attention towards prose in addition to poetry. His prose too, like poetry, is the bearer of countless qualities. Among his novels and short stories which he has written, Pistol Shot and The Postmaster have the status of classics. His short-story The Queen of Spades occupies a very high place in the romantic literature of Russia. From an artistic point of view, this short-story is free of all types of artistic faults. It unveils both aspects of Pushkin’s genius. It reflects a deep love for the Western spirit and the land of Russia. This imaginary fable is witness to Pushkin’s amazing imaginative power. Though the subject of this short-story is extremely imaginary, with this quality, it consists of such psychological elements which carry it nearer to reality. The scene in the story which follows is like reality which presents a very clear picture of the high society in the reign of Alexander II. The old countess represents the French culture of the 18th century.

On 8 February 1837 Pushkin was fatally wounded while fighting a duel and after two days departed, leaving those longing for literature athirst.

(Mikhail) Lermontov had composed the following verses on the death of Pushkin:

‘The sweet melodies are silent!

Even their final echo is extinct!!

His resting place is narrow and dark

The singer’s lips have been sewn!!!’