by Aziz Ali Dad

Let me start this review of the book “Hunza Matters: Bordering and ordering between ancient and new Silk Roads” by indulging in subjectivity. In 2015, I was a Crossroads Asia fellow at Modern Oriental Institute in Berlin, Germany. As a part of socialization, we interacted with different researchers and members of academia. On one weekend my supervisor and I were invited by Hermann Kreutzmann and his wife Sabine Felmy for a dinner. Hermann served as the Chair of Human Geography and Development Studies at Freie University Berlin, Germany. Recently, he retired from the university. His home is a treasure for researchers especially those interested in High Asia. He presented his book “Pamirian Crossroads: Kirghiz and Wakhi of High Asia” as a gift to me. It was the result of more than thirty years of research on the Pamir region. My Spanish supervisor commented that patience and investing a long time in research is the typical trait of German scholarship. To cut the story short, Hermann replied that he published his work early. He shared that there is a German professor who started writing his book on Gilgit in the 1950s, but it is still incomplete.

HUNZA MATTERS: Bordering and ordering between ancient and new Silk Roads

By: Hermann Kreutzmann

Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden. 2020

ISBN Print: 978-3-447-11369-4 — ISBN E-Book: 978-3-447-19961-2

570 pp.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

The point for mentioning the aforementioned personal anecdote is to underscore the rigour and long-term commitment of German academia to acquire long-term perspective. In today’s world, it has become quite a vogue among journalists and researchers to make a quick foray into a specific area or society and produce knowledge about it. This is not the case with Hermann who has recently published the book Hunza Matters: Bordering and ordering between ancient and new Silk Roads. It is a result of more than thirty years of study, research, annual visits to Hunza for more than 40 years and interaction with the inhabitants of the valley. Hunza Matters is a part of the trilogy of books by Hermann. The first and second parts are Pamirian Crossroads and The Wakhan Quadrangle: Exploration and espionage during and after the Great Game published in 2015 and 2017 respectively.

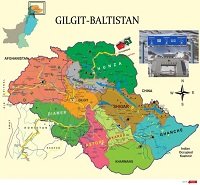

The title of the book encapsulates its theme. The main title Hunza Matters has dual connotations. Matter in the first sense means the issues of Hunza, and the second meaning is that Hunza matters because of its location as it is the pivot of High and Central Asia as well as a gateway between Central and South Asia. The subtitle “Bordering and ordering between ancient and new Silk Roads” connotes two dimensions. The very word “bordering” indicates the process of demarcation of state in the modern age. Due to political developments in the first half of the twentieth century, new demarcations of boundaries emerged in Hunza and the surrounding regions of High Asia. As a result, the organic, cultural, political and historical connections of Hunza with networks in High Asia disrupted. In the book, Hermann seems to imply that what we consider Hunza today is a diminutive shape of historical Hunza. For example, a chart on page 15 of the book shows that from 1761 Hunza experienced gradual severing of its connections and relationships with assemblage or network of High Asia to one-sided subaltern space or under Pakistani administrative and political arrangements.

Secondly, the subtitle implies and emphasizes on the word “ordering” as the postcolonial order robbed the region of its indigenous power base, and imposed exogenous power of administration. Since the whole of Gilgit-Baltistan has been run by administrative orders, the region has been pushed into liminality. Thus the ‘ordering’ here means the imposition of the political, administrative and economic order in which people do not have any say on the one hand, and the imposition of bureaucratic order on indigenous communities on the other.

___________________________________________________

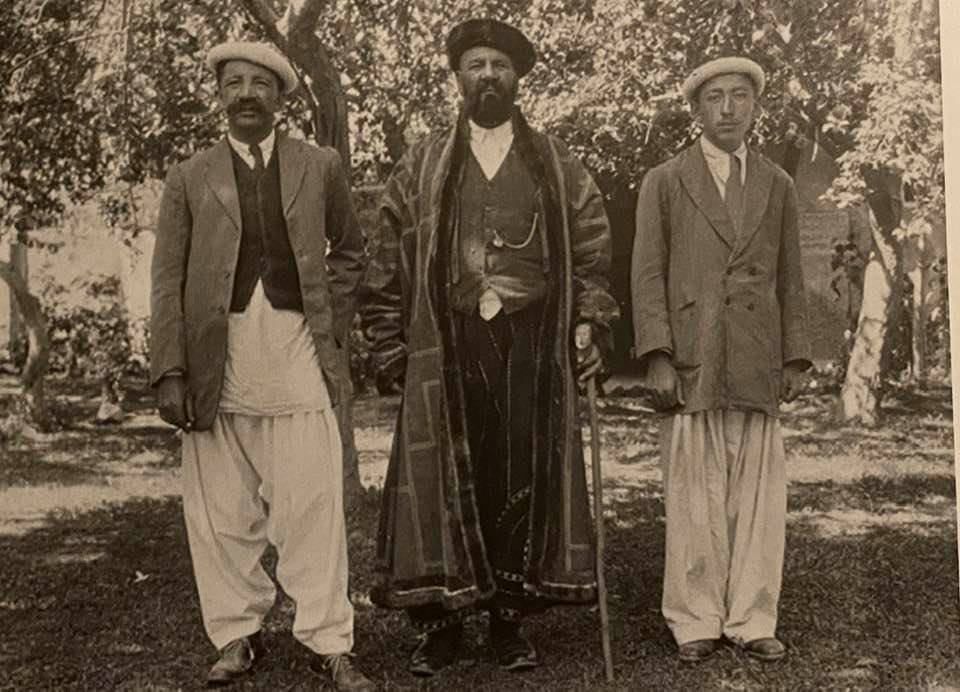

The book mostly covers the period from the reign of Shah Ghazanfar (1824- 1865) to the current scion Ghazanfar Ali Khan of Ayashi family. Interestingly, Hermann uses the word mir with all the previous kings of Hunza, but never uses it with Ghanzanfar Ali Khan. This shows his theoretical clarity as he treats only those persons in history who ruled over Hunza as mir. In the case of Ghanzafar Ali Khan, he never ruled.

The writer clearly states that “the purpose of this book is to shed some light on socioeconomic transformations in the Hunza Valley that enable some insights into the structuration and transition from colonial interference to postcolonial integration, and that identify long-lasting effects of previous deformations and hint at elements of path-dependency and rootedness.” The division of the book is in congruence with the purpose as, in addition to introduction and Avant-propos, it is divided into three chapters.

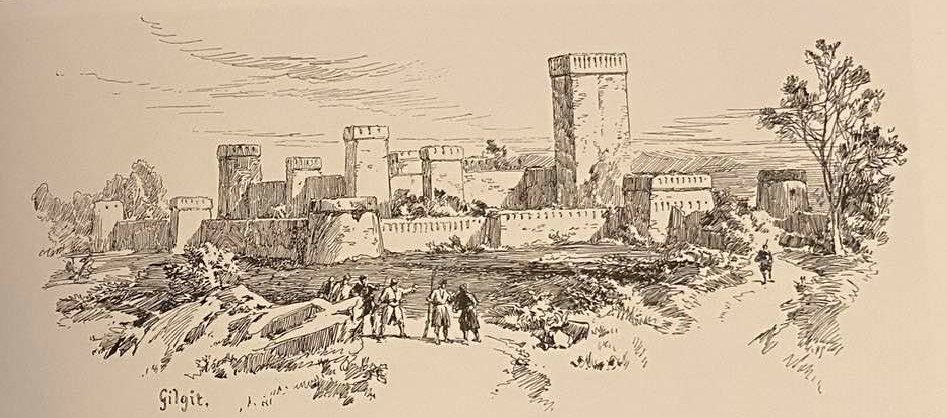

In the initial stage of colonial scholarship about Hunza, human elements were missing. Telescope, cartographers, geographers, compass, maps, and binocular were prominent. All these terms were geared to encompass the hitherto uncharted territories in High Asia. But there are limits to geographical approach. Even now in the official representation of Gilgit-Baltistan, its geography and topography remain dominant at the expense of the human dimension. For instance, the government has recently unveiled a “new political map” including the Indian occupied Kashmir in Pakistan. In the map, Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan are shown in one distinct colour. It means that GB is a part of Kashmir. The missing human dimension is evident from the fact that Pakistan has not yet made the 2017 census of Gilgit-Baltistan available to the general public. That is why we do not see any data from 2018 census in the book.

Scholarship during the colonial period relied much upon Tham, Wazirs and local elites. For instance, in 1930, David Lockhart Robertson, a British linguist and Emily Overend Lorimer an Anglo-Irish journalist, linguist, and writer, spent fifteen months in Aliabad. Hermann claims that they “profited from their close relationship to notables until September 1935”. Therefore, their narrative is influenced by their informants. Instead of single-source, Hermann relies on diverse sources and combines local and exogenous perspectives. The sources for Hunza Matters are maps, journals, articles, newspapers, reports, blog spots, websites, local people, memoirs and archives. In such accounts, the perspective of locals was missing. From Hermann’s account of Hunza, it appears that the scope of sources also kept expanding with the passage of time. With new developments and the emergence of new mediums, a subaltern viewpoint also came forth. In the postcolonial period, “newspaper cuttings, travelogues, and diaries from mountaineering and scientific expeditions, reminiscences from local leaders and respected personalities have provided documents. In recent years articles, autobiographies and collections from local scholars occur in new media and are sometimes offered in print.” Since the appearance of development organisations in the social development sector, a countless number of annual and quarterly reports, consultancy write-ups and ‘grey literature’ have been produced that occasionally contain useful information and sometimes enlightening narratives. The expansion of mediums, research, literacy, sources can be assessed from the fact that at the initial stage of search and research sketches dominated representation and compilation of information about the region of Gilgit-Baltistan, including Hunza. Sooner the sketches were replaced by photographs. The book is a treat for those interested in the visual history of Hunza as it is peppered with rare photographs and maps to support the argument.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Local perspective lies in the interstices and intersection of both indigenous and exogenous perspectives. Hermann not only employs expanded local sources for his research, but he also expands the external sources. Traditionally, British and Western scholarship and accounts inform research about Gilgit-Baltistan. Scholars during the colonial period identified the geographical and political locus “where the three empires meet”. Hermann’s research introduces sources of the three empires to shed light on the history of that locus or pivotal pivot – Hunza — in High Asia. In treating the history of Hunza, Hermann employs Russian and Chinese sources. This is a new finding for the historians interested in the history of Hunza in particular and Gilgit-Baltistan in general.

Hunza got more attention than other areas of Gilgit-Baltistan because of its proximity with three empires: Russian, Chinese and British. It is because of this proximity it got embroiled in the Great Game being played in High Asia. Hunza increasingly got trapped in the pincer movement of Russians from North and British from South Kashmir. However, it proved a hard nut to crack. Hermann shows that once Hunza is vanquished in Anglo-Hunza War in 1891, it became the most obedient state under Tham (mir) Muhammed Nazim Khan. However, it is wrong to assume that British officials were on the same page about the role and scope of the rule of Mir Nazim Khan. For instance, Marc Aurel Stein, the Hungarian-born British archaeologist deemed investiture of Muhammed Nazim Khan as the mir of Hunza as the right and necessary choice. Lorimer painted a picture of Mir Nazim Khan as the “benevolent ruler”. Painting pliant and loyal rulers in good colours is a part of the strategy of colonial power. The representations of local rulers in the colonial period are marked in contrast with dim and unpleasant pictures of the pre-conquest period. Contrary to Aurel Stein’s encomium of Mir Nazim Khan, Reginald Charles Francis Schomberg, a British officer and explorer, writes scathingly about him and dubs him authoritarian and ruthless.

Through meticulous analysis of historical and official documents and sources, Hermann’s book shows changes in “external and internal relations among stakeholders and actors” in Hunza and processes that contributed to the strengthening of Mir Muhammed Nazim Khan, weakening influence of Wazirkuch, expansion of Hunzukuch population into new outside Hunza, increasing role of religion, and exposure of the ruler to new trends and parts of the world.

_____________________________________________________________________________

When it comes to Mir Nazim Khan, people of Hunza and local intelligentsia speaks about the phenomenal expansion of Hunzukuch into different parts of Gilgit. Thus, he is considered a worthy ruler who increased Hunza’s influence in other regions. Nevertheless, what is ignored in this narrative is the fact that it was in his reign that the process of the severing of Hunza from neighbouring regions in High Asia started. Hermann claims that the colonial administration was unhappy with the Chinese connection of Mir of Hunza. Upon British insistence, Mir Nazim Khan gave up his claims for “grazing taxes beyond the Kilik and Mintaka passes and levy pasture taxes in Taghdumbash Pamir and Sarikol and to cultivate his own land in Raskam.” For that, he was “compensated with cultivable land in Oshikandas and an increase in his subsidy.”

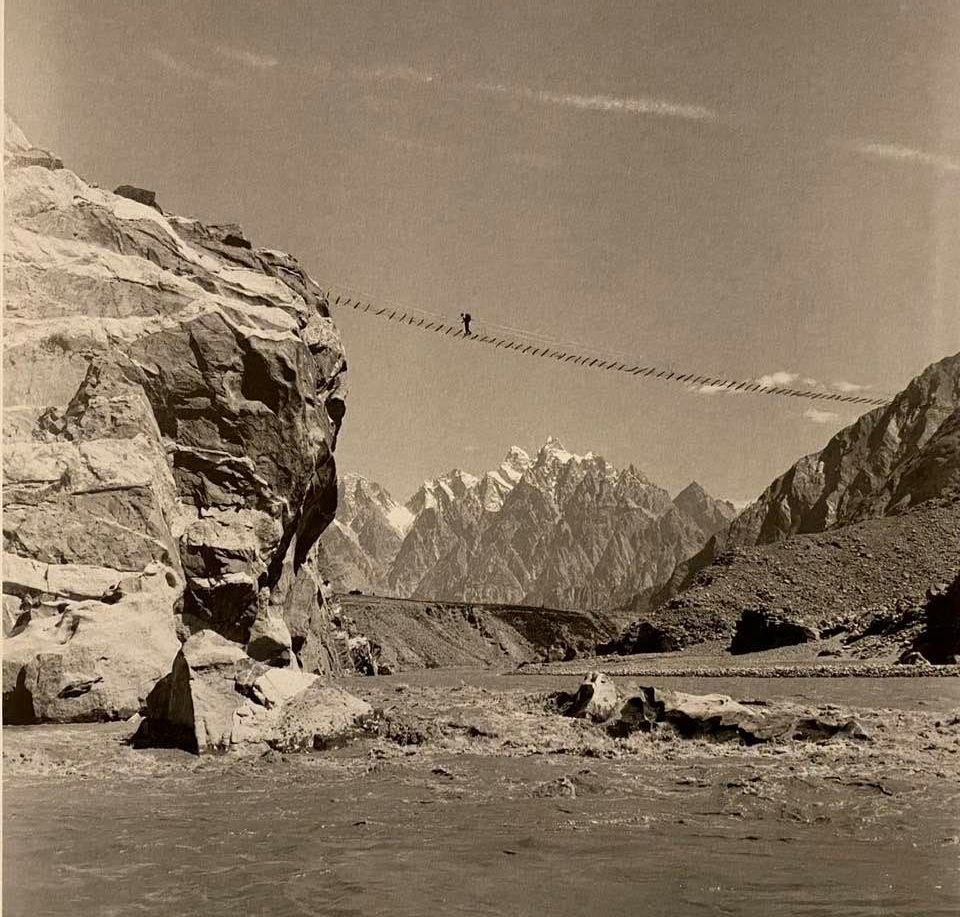

From pony track to corridor

Hunza Matters also narrates the story of passage from pony track to economic corridor now. The typical picture of Hunza as an inaccessible and isolated place with mighty mountains, glaciers, fords, rope bridges, porters and narrow passages was gradually replaced by the expansion of movement from compulsory foot walk and horse fording to Hunza Road and the Karakoram Highway (KKH) to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Hermann challenges the myth of isolation perpetuated by local rulers, policymakers and consultants. According to Hermann, these developments impacted the valley’s communication and exchange relations. In light of these developments, Hermann unpacks the modernization processes and strategies in Hunza. He sees modernization strategies in Hunza as instruments for access, control and exchange. It was the modern instruments like telegraph, road, map, census, postal service, documentation and statutory laws that have brought areas in the peripheries under the control of the centre. In the case of Hunza, telegraph and post office services were introduced in the far-flung area of Misgar near Chinese and Russian border in Hunza in 1918 well before the construction of Hunza road and introduction of other modern services. Now the telegraph service is no more available in Hunza, but it has become the gateway for fibre optics laid as a part of CPEC initiatives. Hunza Matters meticulously documents and analyses the developments in outward communication and its impacts on society, power relations and even perspectives of locals.

_____________________________________________________________________________

Development & modernization

Generally, in the writings about development initiatives and modernization process in Hunza, local perspective tend to be missing. Hunza Matters unravels the perception of local rulers about major developments. Construction of KKH was fraught with anxieties, fears and suspicions not only among general populace but also in the ruler. To explore this issue, Hermann refers to official minutes of Ian Sutherland, the Head of South Asia Department in the Foreign Commonwealth Office, dated 11 May 1970. It is said that Mir Jamal Khan had become suspicious of the pace of change and feared that the Chinese would “eventually take over Hunza.” These fears and suspicions resonates even today. Fifty years on, the book Hunza Matters captures fears of expropriation of resources, one-sided exchange, exclusion from decision making in CPEC, economic participation, and rollback of political powers for the sake of stability in the region for smooth implementation of CPEC projects. The book also sheds light on the circumstances and compulsions that led to the realignment of the KKH, and selection of Khunjerab instead of Kilik and Mintaka. Hermann is of the view that this is done to avoid Russians.

Most of the time the issue of inaccessibility of Gilgit-Baltistan is treated as the greatest impediment for any initiative. But Hermann treats inaccessibility as strategic as “narrow passages were also defence measures and control posts at the same time”. In terms of communication infrastructure, rope bridges (gal) were mostly used in Hunza for crossing over the river. After the conquest of Hunza and Nagar in 1891, British installed bridges at several places from Gilgit to Hunza. British made attempts to connect Hunza with the rest of the world through a network of bridges and road. They also tried to establish aeronautical communication. The book provides rare maps, photographs and sketches from the survey for proposed sites for landing grounds. Rare photographs of airport sites of KIU, Passu and Sost are provided in the book. Also, it documents the arrival of the first mechanical vehicle in 1937 in Gilgit.

The increasing connectivity of Hunza with the outside world through the modern communication network, especially KKH, has transformed the economy, politics, culture and society. It has become almost a cliché among layman and researchers about Gilgit-Baltistan to solely attribute modernization in Hunza to the KKH and to some extent AKDN. Hermann debunks this approach. Instead of finding roots of modernization in road infrastructure of the KKH or AKDN, he traces its roots back to the colonial time in administrative setup and agriculture sector “when packages for ‘modern’ crop-farming and animal husbandry were implemented in addition to administrative reforms and road development that served mainly military and strategic purposes.” Some of the articles that are considered indigenous to Hunza today were introduced during colonial time. These crops include cotton fabrics of white and grey colours, salt, tea, rice, potato, sugar, tobacco and spices. British administrators reported that some of the goods like ‘Soviet sugar, matches, cotton piece-goods, carpets were available’, but ‘there is very little ready cash in those States.” It is the journey from that state of the cashless economy to a thriving cash economy on the KKH and then virtual cash corridor of CPEC that Hermann’s book captures with relevant data and documents.

New order

Besides political, administrative and economic transformations, Hunza Matters explores the contours of the newly-emerging social contract in tandem with changes in other spheres of society. So far no research has been undertaken to explore new social contract in its entirety, though there are institution, symbols and activities that are a part of the new order. For example, the establishment of cooperative societies, village and women organizations, local support organisations, student unions, sport and welfare organisations and standardization of religion are hallmarks of the new order. Hermann adumbrates the idea by broaching how initial capital was created by introducing different packages. At initial stage small holders invested in their agricultural assets. At a later stage, value chains were expanded. The cash generated from the initial investment in agriculture is invested in education. Now the economy of Hunza is mainly supported by the service sector as its diasporic professionals are spread over Pakistan, Middle East, Europe and North America. Hermann calls this transformation as the transition from ‘cooperative capitalism’ to ‘corporate globality’.

Taxing task

One of the difficulties in research about Hunza is the orality of history. Because of this not much historical record and documents available. Even the oral sources are rapidly fading from the collective memory of the people of Hunza. In such a documentary aporia, dealing with quantitative data is a taxing task. Despite these impediments, the book deals with the taxation system in Hunza and provides details of taxes imposed on different parts of Hunza from the late nineteenth century till the modern period. One of the benefits of collecting a wide and heterogeneous array of historical sources is that the reader comes to an understanding of what has been washed from one’s memory. Because of this amnesia, the local people view some vocations antithetical to Hunzukuch’s identity. For instance, today gold washing profession is attributed to a particular ethnic group called gold-washers (jalawaan or marooch). Like an archaeologist, Hermann digs through historical documents and reveals the forgotten aspects of history. This enables him to reinstate the fact that Hunzukuch used to pan gold dust on the pages of history. It was part of forced labour duties – rajaki.

With evidence culled from historical statistics, Hermann’s argument corroborates with the general Gojali narrative about the persecution of their folks of the rulers of Hunza. Hermann is of the view that the rulers, especially Mir Nazim Khan, exempted Burusho and Shinakis and extracted taxes from Gojal. However, “the growing number of gushpur causes greediness of rulers and exploitation of poor from Shinaki, Brusho and Gojal.”

Religion, power & myths

In Hunza Matters, the rule of all the last three mirs of Hunza – Nazim Khan, Ghazan Khan and Jamal Khan — appears to be non-denominational. Although Ghazan Khan did not believe in the divinity of the Aga Khan, in his later life he appropriated religious role because of his diminishing power, dwindling income and increasing role of religion in Hunza. Historically, religion did not play any role in the politics of Hunza. It is in stark contrast to Ghizer and Chitral where religion rebels against the local rulers. This explains the deep-rooted influence of Piri system in Ghizer and complete absence of defunct piri system in Hunza. This is not to claim that there were no religious differences or conflicts. The book documents sectarian unrest in Hunza in March 1937 when twelver Shias from Ganesh, Silganesh and Garelt rebelled against the mir of Hunza against his oppression. It appears that with the increasing role of religion, the sectarian divide increased.

After the conquest of Hunza, the people associated with old power structure were either exiled or irrelevant. Safdar Ali Khan died in the state of penury in Kuchar, Xinjiang, in March 1931. The installation of new mir provided new actors to emerge on the power turf. In this power struggle, the traditional roles of specific clans, such as Wazirkuch, started to lose their power. Hermann shows in detail how Mir Muhammed Nazim Khan consolidated his power after the death of Wazir Humayun Baig in 1916. In November 1935, Nazim Khan dismissed Wazir Shukrullah Beg and appointed Zarparast from Ghulwatiʼn lineage within the Burooʼn as wazir. Appointment of non-Tharakuch Wazir is a cue to drastic changes within the traditional political system of the micro-state of Hunza. This aspect in the book nullifies the perspective that takes the traditional governing structure of Hunza state as immutable and actors as the perpetual power wielders.

At the economic level, Mir Nazim Khan succeeded to increase his income by establishing new villages and relying on an allowance from the British. This is in addition to the money tham (mir) earned from religious tithes. The need for a new source of income was necessitated by the work-shy nature of the members of the royal family who kept their luxurious lifestyle despite dwindling income. Hermann terms it Gushpur problem. During Mir Nazim Khan and Jamal Khan times, the tithes of Ismailis from Badakhshan, Chitral and Gilgit Agency came under their control. This explains the gradual tilt of both not so religious mirs towards religion.

During the colonial period, there is a shift from pir to Imam in Ismailis. In 1923, personalization of real estate of Imam commenced and jamaatkhanas were introduced in Hunza.

Twilight of mirdom

In the post-colonial period, Mir Jamal Khan got another opportunity of income in the form of guests, development projects, tourists, gifts and expeditions. Unlike his grandfather, Mir Jamal Khan’s lifestyle became more European than Hunzukuch. The newly acquired money and gifts enabled Mir Jamal Khan and his family to visit major European cities, where he was introduced to European elites. It is in his reign, exoticisation and romanticisation of Hunza started. Hermann shows that the popular myths about hidden paradises, Shangri-La, absence of beggars, Hunza water, longevity and organic food are the products of the modern age, not a reality. These myths later fused with marketing techniques and created a surreal not real image of Hunza. By the time of Mir Jamal Khan, the authority of mir was diminishing as he relied more on outside sources to keep the system intact. His was the reign when Hunza entered into the twilight of mirdom as the traditional system was disintegrating giving space to new actors from the common folks of Hunza. The book explains the shift from traditional to Ismaili institutions and increasing reliance on external food supplies. It mentions the difference in pasture management between Wakhis and Burushus. Wakhi tradition allows women to go to pastures but not Burushus. Although Hermann does not mention that in Shinaki groups, women were also prohibited to enter into the pasture. The reason is that in the worldview Burushu and Shin groups, pasture is considered an abode of fairy. Therefore, its sacredness is maintained by keeping women at bay. It shows the same worldview of the latter two and difference from Wakhi worldview. Hence, a clue to understanding the current endeavours of Wakhis for their own distinct identity as Gojalis than the collective identity of Hunzukuch.

_________________________________________________________________________________

The gushpur problem remained unresolved even after the abolishment of the Miri system in Hunza. After the abolition of Hunza State, the sources of income dwindled for Ghazanfar Ali Khan. To sustain gushpuric (royal) lifestyle and image, members of the royal family sold hereditary lands and made investments in the transport business. According to Hermann “none of these attempts provided a steady cash flow, more lucrative sources needed to be tapped. These were found in political representation and development activities. In both cases, infrastructure development and the allocation of funds for contractors provided a share for influential and powerful actors.”

If seen in totality, the book also documents waning of authority and decision making in the royal family. Hunza Matters concludes with documenting the loss of authority of Ghazanfar Ali Khan and his son Salim Khan’s disqualification from membership in the Gilgit-Baltistan Assembly. Hunza Matters is the story of dwindling of authority and sources of income for ruling family over time, and increasing opportunities and expanding horizons for common Hunzkuch. That is why they have succeeded to progress from serving as soldiers in the colonial period to shopkeepers in the post-colonial period. After the opening of the KKH, it is the common people of Hunza who established business, and cooperatives that helped in the creation of capital, which in its turn was invested in education and purchase of lands and properties outside Hunza. Now the educated professionals have created corporate globality. For these reasons Hunza matters and Hunza Matters successfully encompasses all these dimensions.

The main problem in dealing with the history of societies like Hunza is the modern epistemological tyranny. Within the modern epistemic order, the orality of culture is looked down upon for it does not provide a chronological and linear narrative. Within the modern episteme of history, the societies that do not fit within the criterion of ethnicity, language, script, certain administrative and traits are expunged from the club of history. When a certain society or people fail to fulfil these Eurocentric epistemological criteria, the people are declared “people without history”. Such people can only be restored to the pages of history and represented only through the processes and criteria that define the society of researcher. When one imposes criteria of one’s “other” culture and look at the history of “other’ societies through the binary opposition of “we” and “you”, then we get a distorted view of history. The Orientalist strain in the colonial scholarship about Hunza creeps in from this approach and hubris. Seen in this way Edward Knight, Francis Younghusband, Reginald Charles Francis Schomberg, Edmund Barrow, Biddulph, Lorimer and others appear Orientalists who have an ethnocentric and power-centric view of locals of Hunza.

Hermann in this book explore the theme of Orientalism in Hunza by closely reading the texts and contexts. As an example, he refers to opinions and views of major scholars in colonial time. For example, when Mir Safdar Khan refused to accept British demands, he was dubbed backward, barbarous, insignificant, impertinent and bold. Schomberg’s writings have ubiquitous presence of negative traits of laziness, dirtiness, inaptness, stereotyping etc. Hunza Matters analyses the writings of Schomberg and shows the pejorative and prejudiced nature of his scholarship. Unlike British, Russians were not directly involved and in direct control of the matters of Hunza. Despite the physical absence of the power of Russia in Hunza, Bronislaw Grombchevsky declares the Kanjutis unkempt and dirty and full of lice everywhere. Later German-Austrian Himalaya-Karakoram expedition in 1954 repeated the same stereotypes of dirty, louse-ridden and glitrous Shin.

One of the fortes of the book Hunza Matters is clarity of conceptual or theoretical issues. Instead of employing a repertoire of modern categories from the modern epistemic regime, Hermann explores the issue in detail and then conceptualises it. The beauty of the book is that it conceptualizes practices in the shape of charts, tables, graphs and calendars. Since the book has a diverse range of sources, it is helpful to expand the horizons of research. Coupled with this, the four decades of field experience of the writer enabled him to gain a long-term perspective, and thus helped him to avoid stereotyping typical of Orientalist scholarship. So far most of the researches about Hunza are oblivious of the direct or indirect impact of Russia on the local politics in the colonial and postcolonial era. The book provides ample Russian sources to explore relevant issues in detail. The glossary of important terms and toponyms are helpful in understanding words of local languages used in the book.

Despite its methodological rigour, conceptual clarity, attention to details and long perspective, the book misses several matters of Hunza in detail. While reading the book, one feels the matters and perspectives from Shinaki is missing as central Hunza and Gojal gets more attention and space. In the list of conflicts over land and pastures, the disputes between Murtazabad and Hini over Chikas, and Khanabad and Mayun with Hussainabad over Bayes in Hunza Shinaki is missing. Similarly, in the charts of lineages of Burushu clans, Hamiyakuch in Diramiting, Chusating and Jaturikuch in Buroon are not mentioned. The clan system in Shinaki, Ganishkuch and Altit is not dealt with in the book. Also, there is no discussion of an important aspect of perception within Hunzukuch about their fellow groups. For example, how Burushus, Wakhis and Shinakis view one another. The historical and cultural perception about “others’ still informs politics, relationships and economy of Hunza. Overall, the book does not treat Hunza as “others” but provides historical perspective about the matters of Hunza through emic and etic perspectives. Overall, this is a must-read book for the readers who are interested in understanding processes, factors and actors that contributed to the unmaking of old Hunza and making of modern Hunza.

Aziz Ali Dad studied Philosophy of Social Sciences from the London School of Economics and Political Science, UK. He was Crossroads Asia research fellow at Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin, Germany, and a research fellow of Asia Leadership Fellow Program in Tokyo, Japan. His research focuses on the history of ideas and the sociology of margins. Aziz regularly writes for the mainstream media of Pakistan on issues related to philosophy, subaltern and peripheral communities of High Asia. With interests in philosophy, identity politics, culture and issues of Gilgit-Baltistan, he is noted for his pioneering work in understanding history, politics and cultural dynamics in Gilgit-Baltistan. He can be reached at azizalidad@gmail.com