History remains the slave of victors only when people internalize the master’s version of history. History can be salvaged, retrieved and appropriated through multiple and even in mundane sources not necessarily sublime one, writes Aziz Ali Dad.

By Aziz Ali Dad

History is an enigmatic discipline because it deals with events of the past but its understanding tends to change under the influence of changes in perspective in the present and emergence of new documents or shreds of evidence from the past. So it can be said that despite its occurrence in the past, history remains active in the present. It is the presence of history in us, that colours our view of the present. Seen in this way, history can be treated as a dynamic process not static event frozen in the past. History remains the slave of victors only when people internalize the master’s version of history. History can be salvaged, retrieved and appropriated through multiple and even in mundane sources not necessarily sublime one. In the act of appropriation, instead of rejecting we turn the tables against victors and oppressors by deploying their utterance as tools against dominant narrative, and make more space for subaltern point of view.

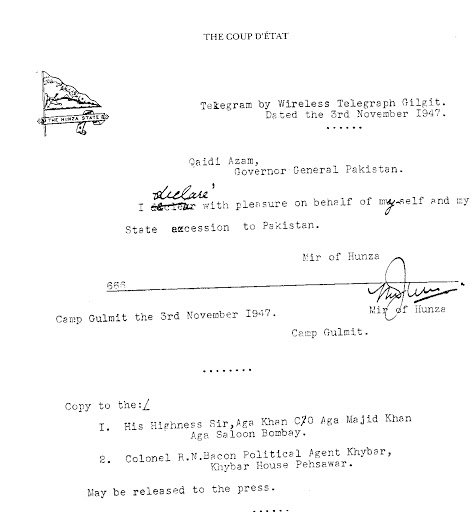

Recently, Fazal Amin Beg, an anthropologist and researcher from Gojal, Hunza, shared audio of a speech by late Mir Muhammed Jamal Khan of Hunza, the last ruler of Hunza, in 1972 during the occasion of an Eid gathering. The speech is delivered in Burushaski, but for non-Burushaski speakers, Fazal Amin has rendered it into English. It has helped in widening the audience of the speech and proved helpful for researchers to restore subaltern voices on the pages of history. Fazal Amin Beg efforts are laudable in this regard.

For a proper understanding of the speech, it is indispensable to situate it in its historical period and political context. The speech was delivered at the twilight time of Hunza state’s long history as two years after this speech the Hunza state was dissolved. Urdu in the 1970s was quite an alien language for the majority of people in Hunza. However, the oration of Master Sultan Ali alias Samarqand Ustad in welcome speech is impressive. After his introducing remarks, Mir Muhammed Jamal Khan delivers his speech. One of the salient features of the speech is the excellent oratory skills of Mir Jamal Khan in Burushaski language. It also provides insight into the role of the local language in the formation of political language and discourse. The prefacing of speech by Mir Jamal Khan in Urdu by Sultan Ali provides a cue to increase the role and intrusion of Urdu as the language and representative of the power of the state of Pakistan. At the same time, Mir Jamal Khan’s speech in Burushaski points towards two important aspects of power relations and cultural dynamics in Hunza.

Mir Jamal Khan seems to accept modernization of religion and even rupture in traditional set up of religion but refuses the same process for the political system of the state of Hunza

Although Sultan Ali was also a scion of the royal family, he made a mark in the field of education as one of the pioneers. His choice of Urdu in speech and profession of a teacher is diametrically opposite to that of Mir Jamal Khan who holds the reins of traditional structures of power. Sultan Ali represents a snippet of the new order of things to be emerged in the future, whereas Mir Jamal Khan is representative of traditional order that was increasingly losing its relevance. Sultan Ali’s vocation and profession do not need a hereditary right or royal lineage but certain skills and modern knowledge.

Mir Jamal Khan also had exposure to the modern world including Europe and modern education, but he geared to experience and education to perpetuate his tottering rule and maintain eroding legitimacy, which was under threat from a movement spearheaded by disgruntled youth of Hunza. It is to provide legitimacy to his rule, he shifts the basis of legitimacy from traditional social contract to religion and its attendant discourse of modernity and modernization. Interestingly, modernity in Hunza is not introduced by a secular institution of king or state. Rather it is introduced by religion. Hence, we can say that experiences and processes of modernity in Hunza defies the modern way of attributing it to is secular domain and institutions which creates a rupture in traditional worldview and the social contract. The very term constitution is a modern construct. It was an alien nomenclature for local discourse or repertoire of words employed to define the indigenous system of governance and society. The Ismaili constitution that Mir Jamal Khan has referred to in his speech is a part of the modernization process first introduced by Sir Sultan Muhammed Shah and continued by his successor Iman Shah Karim Al Hussaini. The new constitution was a prologue for changes in procedures, religious arrangements, rituals and roles of Ismaili religion. It has also contributed to creating a rupture in traditional arrangements to manage religion. The newly introduced constitution would provide space to impersonal institutions where personalities will have little role. That is why piri system is not strengthened in the new constitution and its attendant institutional arrangements. But Mir Jamal Khan employs a religious contract to legitimize his politics wherein he was the sole suzerain of Hunza state.

In his speech, the ruler of Hunza (Mir Muhammed Jamal Khan) seems to accept modernization of religion and even rupture in traditional set up of religion but refuses the same process for the political system of the state of Hunza. That is why he admits the equality of all people before the Ismaili constitution. At the same time, he never mentions any initiative of political reforms except few tax exemptions. Mir of Hunza was visibly perturbed by new developments, such as dissident student movement against his tyranny. Because of this, he labels new political ideas and emerging dissent within the young generation as wrong ideas (ghalat khayalat) and incorrect propaganda (ghalat propaganda). He mockingly terms the dissenting youth as a “couple of urchins” (walto joto)”. In the Burushaski and Shina languages, joto has two meanings: urchin and chick. In other words, Mir Jamal Khan calls the youth opposing him “chicken-hearted”. He again deploys the religion to delegitimize his opponents by indirectly alluding to the event of raising flags of a political party (it refers to raising the flag of PPP by youth political activists) as an act of leaving the shadow of the flag of Imam.

Founding leaders of the Hunza-Nagar Liberation Movement at Aga Khan Gymkhana, Karachi in 1968. Photo: HAH

Founding leaders of the Hunza-Nagar Liberation Movement at Aga Khan Gymkhana, Karachi in 1968. Photo: HAH

Instead of introducing political reforms or a constitution for his state, he declares the Ismaili constitution a political document. ..For Mir Jamal Khan religion was also a political party.

Again, Jamal Khan’s use of the term signature (dastakhat) is indicative of eroding meaning and relevance of the vocabulary of traditional discourse and the social contract, and desperate attempt on his part to make sense of the old order of things through notions and practices derived by modernity. It is the point in the history of Hunza when technologies of control in Hunza shifted from traditional to modern. Also, Mir Jamal Khan rejects the allegation that he had penned the constitution. Indeed, it is a fact that Mir Jamal Khan did not write the Ismaili constitution. A deconstruction of the statement denotes the diminishing power of Mir of Hunza. For example, by refuting his authorship of the constitution, Mir Jamal Khan clearly shows that he is no more the author of the destiny of Hunza state and its people but had to rely on outside powers. Instead of introducing political reforms or a constitution for his state, he declares the Ismaili constitution a political document. He claims that it covers domains of political, material and hereafter. In other words, the constitution provides an answer to the political questions as well. “I’m not a slave of any party. I don’t belong to any party. And if I’ve any affiliation, I belong to the Imam’s party” Mir Jamal Khan declares. For Mir Jamal Khan religion was also a political party. That is why he declares himself a member belonging to the party of Imam.

Although Mir Jamal Khan claims to have protected Hunza, he does not mention his role or no role in the handing over of 750 sq km land of Hunza to China in 1962

For the researcher of international relations, the time and personality of Mir Jamal Khan provide rich data for analysis. He was the then President of the Shia Ismaili Supreme Council for Hunza and Central Asia. Therefore, his decisions and thoughts have a regional dimension to it. Although Mir Jamal Khan claims to have protected Hunza, he does not mention his role or no role in the handing over of 750 sq km land of Hunza to China in 1962 in a treaty between China and Pakistan. His reference to Imam’s description of Mir with his signature in writing “Long Live Mir of Hunza, Long Live the Community of Central Asia” can be viewed as an act to reassert his suzerainty over Hunza and influence over Hunza and neighbouring regions. He goes to the extend of terming Hunza an Ismaili state that would live till eternity despite the change of rulers.

Today, the separation of politics from the social sphere in Hunza has started to take its toll

The speech of Mir Jamal Khan reveals that he himself had a realisation of the sentiments of antipathy against him among the masses of Hunza. The antipathy coupled with political developments in Pakistan and increasing irrelevance of Hunza state in regional politics, has dwarfed the political influence and power of the Hunza state. This has created dread in Mir Jamal Khan regarding the role of Hunza at the twilight of its history. It is this dread that compels him to use the word “end” 9 times in his speech. Most of the time, it is employed to point towards the end of his rule or the state of Hunza. As the darkness starts to grow at the time of twilight, the light gradually disappears, and ultimately, darkness engulfs the horizon. It is the lack of clear vision about the future of Hunza at the time of dusk that caused Mir Muhammed Jamal Khan to surrender to the federal power without required guarantees and conditions. Since then Hunza has descended perpetually into political darkness, though the people manage to developed socio-economically. Today, the separation of politics from the social sphere in Hunza has started to take its toll. Incarceration of 12 young political activists of Hunza and its status of being an alone political orphan in the shape of the absence of the presence of Hunza in Gilgit-Baltistan Legislative Assembly (GBLA) perfectly depicts the political poor and the weak state of Hunza.

Aziz Ali Dad is a social philosopher with an interest in the history of ideas. He holds a degree of MSc in Philosophy of Social Sciences from the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is a columnist for The Friday Times and The High Asia Herald. Aziz has written extensively on philosophy, culture, politics, and literature. He has published research papers at national and international levels. He has been a Crossroads Asia Fellow at Modern Oriental Institute, Berlin in Germany, and a fellow of Asia Leadership Fellow Program in Japan. Email: azizalidad@gmail.com