Any border deal will have to consider shared water infrastructure

Ayzirek Imanali, Kamila Ibragim

Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan may be inching closer than ever to hashing out a border delimitation deal that will end decades of territorial ambiguity.

Less talk has been devoted, however, to the mechanisms for sharing and managing precious water resources. Until that happens, deadly conflict like that which erupted in late April may again occur.

Fighting on April 28 began over a deceptively ordinary chunk of infrastructure.

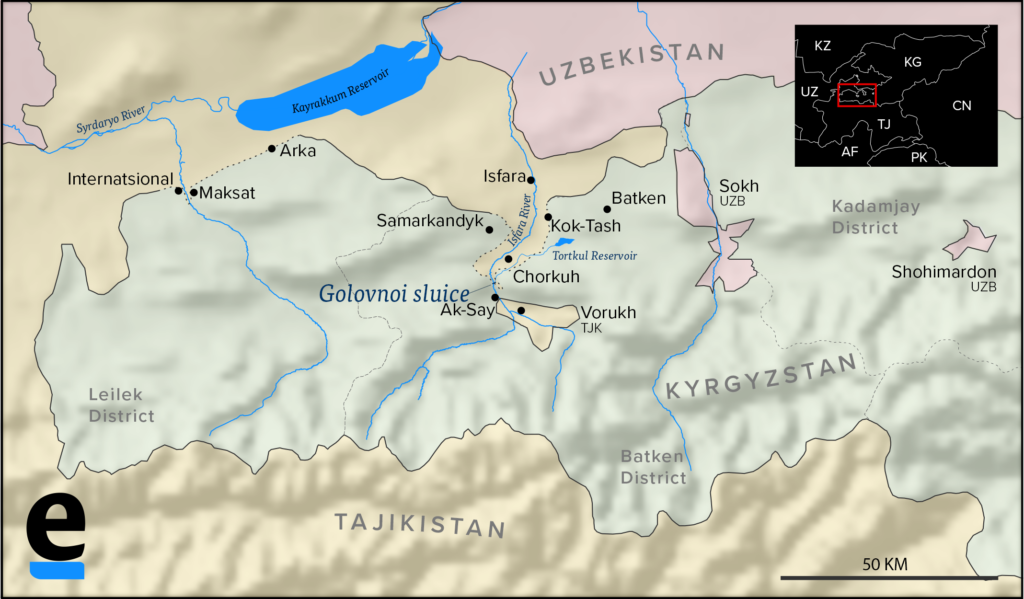

The Golovnoi water intake facility, the construction of rusting steel locks and concrete, serves a simple function. It splits a river – known as Ak-Suu by the Kyrgyz and Isfara by the Tajiks – into two.

The river proper courses northward along its natural path, weaving alongside fields alternately claimed by Kyrgyz and Tajik villagers before ending fully inside Tajikistan and then eventually in Uzbekistan.

A spur created by Golovnoi runs through a canal – dubbed, with painful irony, the Friendship Canal – through a mountain bored by Soviet engineers and ends up in the Tortkul reservoir inside Kyrgyzstan, about 16 kilometres away as the crow flies. That pool of water is mostly used for fields in Kyrgyzstan, although some again get rerouted back to Tajikistan. The arrangement means all sides should benefit.

Reality is messier

When a Eurasianet correspondent approached Golovnoi from Tajikistan on May 2, she was met by Tajik border guards. The troops were welcoming if nervous, demanding that no photos be taken. They later relented on this point but insisted that no faces be shown in photographs.

On the other side of the river stood Kyrgyz border guards, armed like their Tajik counterparts. Unseen snipers and gunners of both nations watched from the hills above. The Kyrgyz border guards shouted and gestured demands for an explanation as to the identity of the Eurasianet correspondent. This unnerved their Tajik colleagues. The brief tour was quickly brought to an end.

The scene was a vivid illustration of the trigger-hair sensibilities around the facility. The governments of the two countries tell slightly different stories about Golovnoi.

Also read: https://thehighasia.com/kyrgyz-tajik-battle-leaves-31-dead/

Rustam Shomirsaid, head of water and land resources management in Tajikistan’s Isfara district, disagrees. He says Golovnoi has not undergone any repair for the past 12 years. And that it was in fact the attempt at reconstruction work undertaken by the Kyrgyz in April that sparked this latest round of unrest in the first place.

“We could not afford to unilaterally repair the structure. But if they repair it, it will mean that the facility will become completely theirs,” Shomirsaidov told Eurasianet.

Even though dozens died in armed clashes over this disagreement, Kyrgyzstan appears determined to proceed with its previous plans. Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov on May 7 accordingly ordered that the water distribution point be overhauled.

It was this very potential eventuality that the Tajiks say they were trying to avoid on April 28, when they arrived at Golovnoi and began installing surveillance cameras. The idea was that the Kyrgyz would be spotted if they started doing any work that had not previously been agreed upon.

This should in theory not matter, since agreements are in place determining how much water goes where. Under a 1980 protocol, 55 percent of the river flow is earmarked for Tajikistan, 37 percent for Kyrgyzstan, and another 8 percent for Uzbekistan.

However, these are abstractions difficult to enact in such exact terms. Needs on the ground have radically evolved in the four decades since that agreement was signed and distrust is intense.

In practical terms, the water distribution is made on a seasonal basis. At peak season — April and May — the Ak-Suu/Isfara flows unhindered towards Tajikistan. Apricots, apples, cherries, rice and wheat are the lifeblood of the economy in Tajikistan’s Isfara region, which holds up to 270 square kilometres of irrigated land.

Nizomiddin Shamsiddin, a resident of Isfara, said farming work makes the difference between being able to stay with one’s family or having to go to Russia for often-demeaning and low-paid labour.

“This is how I make a living myself. If there is no water in [the spring], then there is no sense in having this land. We will all have to leave,” Shamsiddin told Eurasianet.

The rest of the time, much of the flow is diverted into Kyrgyzstan, to the Tortkul reservoir, which can store up to 90 million cubic meters of water.

That is little consolation to those Kyrgyz farmers living along the way from Golovnoi to the reservoir, who rely on what they divert out of the Friendship Canal into the irrigation ditches around their fields. In the crucial April-May season, they are lucky to get a trickle.

Asanbai Miradil, a 54-year-old resident of the Kyrgyz village of Kok-Tash, which lies along the disputed border, says shortages in their area often lead to disputes among Kyrgyz villagers themselves, not just with Tajiks. At times, Miradil told Eurasianet, neighbours will hog water for themselves, depriving his 1,200 square meters of land, which holds 15 apricot trees and several rows of corn, of irrigation. Miradil said this year was especially bad as he had to abandon his home during the fighting that broke out last month.

“I didn’t manage to draw water for myself, so it’s all dry. If I cannot get some water, there will be no crops at all,” he said.

There is an important distinction to be made here between the kind of agriculture being done by Tajiks and Kyrgyz in this area. Tajiks have more arable land at their disposal and production is in a wholly different order from what happens in Kyrgyzstan and a lot of output is, accordingly, intended for export.

Kyrgyz villagers are mostly engaged in subsistence farming. If they have the means to do so, farmers like Miradil will take their cars to wells or water distribution points and drive what they can back home. The water is also used for drinking since the villages are not connected to the mains.

The water-sharing mechanism is complicated by yet another detail. A certain portion of what ends up in the Tortkul reservoir is, also under the terms of intergovernmental agreements, earmarked for feeding westward back into Tajikistan, albeit not to areas adjacent to the river initially feeding this whole chain.

Such situations create a cascade of mutual dependencies. If Bishkek opts to hold back water from Tortkul, the Tajiks can engage in tit-for-tat reprisals at other locations.

“Cutting off water to villages is an extreme method,” said Shomirsaid, the official in Isfara. “[But] Tortkul was built in Soviet times, and it was intended for Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, so that in March-April, when there is not enough water, it could be distributed among other countries, to help each other.”

This is the bottom line: Water is about survival. And surviving requires peace.

Abdumutalib Amakjon, who lives just outside the town of Isfara, cultivates wheat, both for his own family’s use and to sell at the bazaar. His water comes from Tortkul.

“If there is no water, then there will be no life,” Amakjon told Eurasianet.

A short distance away, in Kyrgyzstan’s village of Kok-Tash, Abdrazak Shadi recalls how petty disputes have been occurring for decades. There were times when mobs would overturn cars owned by Tajik neighbours.

But “this issue cannot be resolved through shooting,” he said. “That way, both Tajiks and Kyrgyz will die. We just need to negotiate.”–Courtesy: euroasianet

Kamila Ibragim is the pseudonym for a journalist in Tajikistan.

Ayzirek Imanali is a journalist based in Bishkek.