Two nuclear-armed states shoot down each other’s planes

The last time that Indian and Pakistani jets bombed one another’s territory was in 1971, during an all-out war. In that conflict more than 10,000 soldiers died, over 100 planes were shot out of the sky and Pakistan was torn asunder, as the new state of Bangladesh took shape. But then neither side had built the nuclear arsenals that they wield today. So when the roar of Indian warplanes returned to Pakistan’s skies on February 26th, it marked the most dangerous moment in South Asia since a months-long mass mobilisation of troops in 2002. How did the two countries get into this situation, and can they step away from the brink?

The immediate origins of India’s taboo-busting air raid and the resulting aerial skirmishes lie in a suicide-bombing on February 14th in the Pulwama district of the state of Jammu & Kashmir that killed 40 Indian policemen. It was the deadliest attack in the state, and the worst jihadist atrocity anywhere in India for over a decade. But Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, also faces an election. Hindu hardliners do not feel he has sufficiently advanced their cause while others feel his promise of modernising India to bring jobs has failed. Appearing a resolute commander will do him no harm.

Though the bomber was a Kashmiri, one of many locals who seethe at heavy-handed Indian rule in the state, the attack was claimed by Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), a Pakistan-based Islamist group. That, for India, was the last straw. JeM and Lashkar-e-Taiba, a similar group, conducted spectacular strikes in Delhi in 2001, Kashmir in 2002 and Mumbai in 2008. An attack by JeM in September 2016 killed 19 Indian soldiers, prompting Mr Modi to send special forces across the Line of Control, the de facto border in Kashmir, in what he triumphantly called “surgical strikes”. Such incursions were commonplace in the 1990s and 2000s, but Mr Modi’s willingness to flaunt such brazen raiding publicly was new. Though of questionable military utility, it reaped political rewards.

After the Pulwama attack bellicose news anchors bayed for revenge. Even liberal-minded Indian commentators, who would usually favour talks with Pakistan, demanded that something be done. Mr Modi did do something. A dozen or so fighter jets, equipped with 1,000lb bombs, took off from Gwalior air base on February 26th, crossing both the LoC and a political and military threshold. Indian civilian leaders had forbidden the air force to fly or fire over that line even during a war over Kargil, part of Kashmir, in 1999.

Crossing the line

The planes struck an alleged JeM facility in Balakot in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. India claimed that hundreds of jihadists had been killed. Pakistan snorted at this “self serving, reckless and fictitious claim”. India, it said, had crossed only a few miles into Pakistan and pounded uninhabited jungle for theatrical effect.

Even so, Pakistan’s powerful armed forces, which have ruled the country for much of its history, were left reeling. Indian jets had appeared to come within 100km of Islamabad, the capital, without being intercepted. Pakistan’s prime minister Imran Khan promised to respond at a time and place of his choosing. That did not take long. On February 27th Pakistan said that its own aircraft had struck back. As Indian jets chased the attackers, seemingly into Pakistan, an Indian aircraft was shot down, with the unlucky pilot landing on the Pakistani side of the border.

Neither side is spoiling for a no-holds-barred fight. Mr Modi’s government made it clear that it had sought to attack terrorists, not Pakistani soldiers, far from densely populated areas. Pakistan said it had fired from within its own airspace (though India disputes this) and deliberately struck open ground “to demonstrate that we could have easily taken the original target”, a group of six military facilities.

The torture and mutilation of Indian soldiers sparked national outrage during the Kargil war. The captured Indian pilot has been well-treated so far. Though India protested at his “vulgar” display to the press, he was filmed clutching a cup of chai and praising his captors as “thorough gentlemen”. “The tea is fantastic,” he added. On February 28th Mr Khan unexpectedly announced that he would be released the next day. All this may offer a path to de-escalation. Mr Khan gave a sober and emollient speech after the dust-up, acknowledging “the hurt that has been caused due to the Pulwama attack”. “Better sense should prevail,” he urged. “We should sit and settle this with talks.” But it may not prove as easy as that.

Can calm come?

Mr Modi is a captive of his own propaganda. His policy of loud jingoism has left India with less room for manoeuvre. Srinath Raghavan, a former Indian soldier and respected historian, quotes Abba Eban: “A statesman who keeps his ear permanently glued to the ground will have neither elegance of posture nor flexibility of movement.” One possibility is that escalation will involve the usual means, such as artillery duels across the LoC, which increased on February 27th and 28th, and raids on border posts. That would be troubling but not cataclysmic. However, Pakistan has closed its airspace and put KP on high alert, suggesting that more incursions are feared. India has increased naval patrols and raised security on Delhi’s metro network, reflecting concerns that Pakistan might sponsor retaliatory terrorist attacks.

One Indian expert says that a full mobilisation of the Indian army should not be ruled out. Christopher Clary, who managed South Asia policy at the Pentagon from 2006 to 2009, suggests that America should consider evacuating its citizens from both countries. “Not because we are there yet, but because when the situation warrants it, there will be no time.”

A nuclear shadow also hangs over the crisis. During their last big clash, in 1999, India and Pakistan both possessed nuclear weapons but had only limited means to deliver them. Today India has some 140 warheads and Pakistan about ten more than that. Each wields an array of matching missiles. Pakistan has also built tactical nuclear weapons, with a range of 70km or so, intended for use against invading Indian forces, on Pakistani soil if necessary. Their short reach means they would need to be deployed perilously close to the front line.

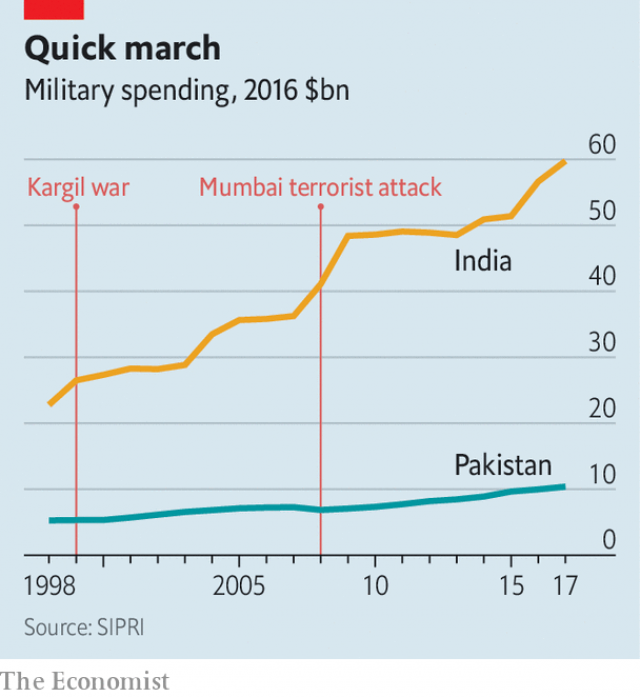

Mr Khan chaired a meeting of his country’s Nuclear Command Authority on February 27th and reminded India of the stakes: “With the weapons you have and the weapons we have, can we really afford a miscalculation?” Pakistan’s aim is to underscore that India, which now spends over five times as much as it does on defence (see chart), cannot bring its conventional military superiority to bear without risking nuclear ruin. It hopes, also, that this chilling prospect will force the international community to restrain Mr Modi.

To Indians, such threats fit with a long pattern of cynical nuclear blackmail stretching back to crises in the 1980s. Some officials share the view expressed in January 2018 by General Bipin Rawat, India’s army chief, that India ought to “call their nuclear bluff”. Hawkish Indians look enviously at Israel’s model of counter-terrorism and chafe at how Pakistani nukes have defanged their more numerous forces.

Any whiff of nuclear weapons would, in the past, have sent outsiders rushing to the subcontinent to soothe tensions. In 1990 President George H.W. Bush sent his CIA director to South Asia to calm a brewing crisis. During the Kargil war Bill Clinton gave Nawaz Sharif, then Pakistan’s prime minister, a dressing down in Washington, DC. In a stand-off that unfolded in 2001-02 everyone from Tony Blair to Vladimir Putin passed through the region.

Today, however, America’s calming influence may be lacking. The Trump administration lacks the experience, expertise and focus to lower the temperature in the same way. It is beset by domestic drama and lacks diplomats in important roles. There is no permanent ambassador in Pakistan and the branch of the State Department which covers South Asia has five acting, rather than permanent, deputy assistant secretaries. “I’ve never seen anything like that,” notes Mr Clary.

Diplomatic language

Donald Trump broke his silence on the skirmishes on February 28th, noting that “hopefully it’s going to be coming to an end”. There are plenty of useful things he could do. One would be to assure India of further intelligence co-operation and defence assistance should it restrain itself from more muscle-flexing. Another would be to demand that Pakistan takes credible action against terrorist groups such as JeM, rather than the cosmetic and ephemeral steps it has taken in the past. Even so, Pakistan is playing a pivotal role in Afghan peace talks by calling for negotiations by the Taliban, which it has long supported. Mr Trump will fear that should India or America squeeze Pakistan too hard, that process, and the prospect of bringing home 14,000 troops, may collapse.

The influence of China is also important. In recent years, it has grown closer to Pakistan, lubricating the relationship with investment and arms, and more hostile to India, with which it shares a long, disputed and occasionally turbulent border. It hopes to show support for Pakistan without being dragged into an unwanted conflict.

The foreign ministers of India, China and Russia met on February 27th and agreed to “eradicate the breeding grounds of terrorism and extremism”. To India, that was welcome language. What Mr Modi really wants, however, is for the leader of JeM to be designated as a terrorist at the UN, something that China has blocked for years to spare its ally’s blushes. Also on February 27th America, Britain and France proposed a ban at the UN Security Council for the fourth time. Another Chinese veto would infuriate India. A change of heart, on the other hand, would make de-escalation more likely.

The ball is in Mr Modi’s court. His hope was that sending jets into Pakistan would dispel old notions of a pacifist India and collect a few votes in the process. But the pictures on the front pages of newspapers might not now be victorious warplanes but an Indian pilot freed by Pakistan.

The wise choice would be to take up Mr Khan’s offer of talks, while trading military restraint for international support. Mr Khan and his generals, who are largely satisfied with their token bombing raid, have made that easier by swiftly promising to hand back the pilot. The temptation, however, will be for Mr Modi to have the last word with another martial flourish. Pakistan would be compelled to respond, risking all-out war. Equanimity, responsibility and sobriety are required, but those are hardly Mr Modi’s strong suits.