How India’s prime minister uses Hindu nationalism

When the world’s biggest electorate handed Narendra Modi a thumping victory five years ago, India seemed poised for far-reaching change. His party had won an outright majority of seats in the national parliament, a rare feat in India’s fractious politics. This was not only punishment for tarnished incumbents or reward for Mr Modi’s hard-working, no-nonsense, business-friendly image. Many also saw it as a ringing endorsement of his ideology. Mr Modi’s strident brand of Hindu nationalism, which pictures Pakistan less as a strategic opponent than a threat to civilisation, puts him at the fringe even of his own Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

After five years in power, the Hindutva (Hindu-nationalist) movement faces a moment of reckoning. That is not just because first Pakistan’s jihadists and then its air force have presented Mr Modi with a political crisis. It is also because India is approaching a general election looking as polarised as at any time since independence.

The rival visions confronting India’s 900m voters have rarely been so sharply defined. Hindu nationalists regard India as a nation defined by its majority faith, much like Israel or indeed Pakistan. On the other side stand those who see India’s extraordinary diversity as a source of strength. For most of the country’s seven decades the multi-coloured, secular vision has prevailed. But the orange-clad Hindutva strain has grown ever bolder.

Under Mr Modi, the project to convert India into a fully-fledged Hindu nation has moved ahead smartly. The pace would undoubtedly accelerate if, carried on a surge of patriotism brought by the clash with Pakistan, he sweeps into another term. But given that in 2014, the BJP grabbed its big majority with just 31% of the popular vote, how far would Mr Modi be able to push the Hindutva project, even if he does get a new mandate? And if he loses, can a secular India be rebuilt?

The answers depend less on politics than on the underlying strength of the Hindu nationalist movement itself. To measure this, the place to start is with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). With an all-male membership of around 5m, the flagship of Hindutva modestly describes itself as the world’s largest volunteer organisation. It is far more than that.

Founded in 1925, the RSS has over time absorbed or co-opted nearly every rival Hindutva group. “The miracle and also the design of the Sangh is that they have not split—and that is their power,” says Vinay Sitapati, a historian. Its most obvious manifestation is the RSS’s 60,000-odd self-financing cells, or shakhas, which meet daily for communal exercises and discussion, typically on a patriotic theme. The harder core of the RSS consists of some 6,000 full-time apostles known as pracharaks. These devotees exercise discreet control across not just the shakhas, but a broader “family” of Hindutva groups.

Keep it close

Keep it close

The family includes India’s largest trade union as well as unions for farmers, students, teachers, doctors, lawyers, women, small businesses and so on. RSS progeny run India’s two largest private school networks, educating some 5m children. One of these, Ekal Vidyalaya, has grown by targeting remote regions where Christian missionaries have made inroads (see chart 1). Some RSS groups exercise quiet influence, lobbying for more “nationalist” economic policy, for instance. Others simply wield muscle. The 2m-member Bajrang Dal, a youth branch of the World Hindu Council, an RSS offshoot, has a reputation for beating up Muslim boys who dare to flirt with Hindu girls. The 3m-strong All India Students Council is aggressive in campus politics. By threat or violent action it frequently blocks events it does not like, such as lectures by secular intellectuals. Just outside the orbit of the RSS lie violent extremist groups, such as one believed responsible for murdering leftist writers.

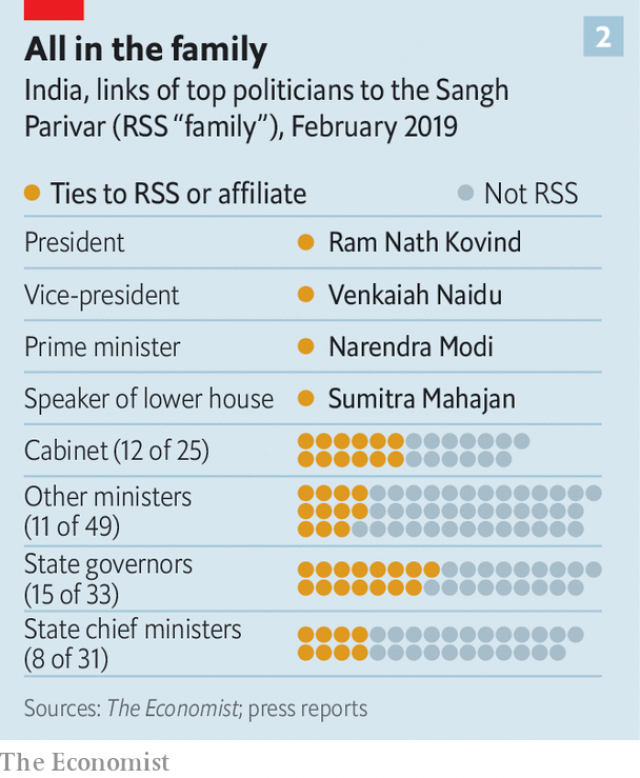

The BJP is a loose affiliate of the RSS. Under Mr Modi, who served as an RSS pracharak before being assigned to the party, ties have been tighter. The RSS has thrown its full organisational weight behind his campaigns. In return, Mr Modi has inserted RSS men—or like-minded ones—into every part of Indian politics (see chart 2). But RSSinfluence also extends to university deans, heads of research institutes, members of the board of state-owned firms and banks (including the central bank) and, say critics, ostensibly politics-proof promotions in the police, army and courts.

Still, frictions have arisen between Mr Modi and his alma mater. “They don’t like prima donnas,” says Mr Sitapati. Quiet purges, as well as a massive broadening of the BJP’s membership to over 100m, have forged a party hierarchy of personal loyalty to Mr Modi that RSS elders distrust. More broadly, there is grumbling in the Hindutva camp that he has not championed their agenda energetically enough.

This includes education “reform” (to inculcate stronger national sentiment and emphasise Hindu identity); ending “appeasement” (a term Hindutva activists apply to policies aimed at garnering Muslim votes); imposing a uniform civil code (to deny a limited role to sharia, or Islamic law); repealing laws that grant special status to the state of Jammu & Kashmir (to underline Indian sovereignty over a disputed territory that has a large Muslim majority); building a temple to the god Ram at Ayodhya (where in 1992 Hindu mobs destroyed a 16th-century mosque said to be built atop his birthplace); and enforcing rules to protect cows.

Mr Modi’s government has met some Hindutva demands. Nationalist staff have been promoted at every level of schooling, subtly changing the tone of education. But many of the RSS’s demands boil down to putting Muslims, already mostly poor and badly educated, in their place. Accounting for 14% of the population, they are generally excluded from caste-based “reservations” for government favours. Among the BJP’s 1,400 state-level mps, only four are Muslim. And in Muslim-majority Kashmir, a perennially vexed region, Mr Modi’s government has hardened policies to tackle militancy, imposing direct rule from Delhi, threatening to end unilaterally Indian Kashmir’s special legal status and endorsing, among other measures, the use of shotguns to blast stone-throwing youths. The approach has alienated Kashmiris and also tempted meddling by Pakistan, ever keen to challenge India’s sovereignty. After the longest lull in three decades of violence, it has spiralled again under Mr Modi.

Violence has also accompanied a campaign in BJP-run states to apply stringent laws against the slaughter of cows, sacred beasts to Hindus. Between 2015 and 2018 some 44 people, 36 of them Muslim, have been beaten or hacked to death by cow vigilantes, says Human Rights Watch, an ngo. The ban has not spread nationally, partly because many Hindus outside the “Cow Belt”—the conservative middle and west of the countryseat beef, and partly through anger among farmers who can no longer sell cows beyond milking age.

Violence has also accompanied a campaign in BJP-run states to apply stringent laws against the slaughter of cows, sacred beasts to Hindus. Between 2015 and 2018 some 44 people, 36 of them Muslim, have been beaten or hacked to death by cow vigilantes, says Human Rights Watch, an ngo. The ban has not spread nationally, partly because many Hindus outside the “Cow Belt”—the conservative middle and west of the countryseat beef, and partly through anger among farmers who can no longer sell cows beyond milking age.

The demand to erect a Ram temple in Ayodhya has not progressed, either. The issue has been stalled in courts for decades. Mr Modi has tried to push India’s Supreme Court to resolve the case, but his influence is limited. In recent weeks the RSS appears to have quietly advised its affiliates to stop agitating over the issue. This suggests a recognition that, although the demand once galvanised mass emotion, most Hindus are now more concerned with matters such as jobs, schools and health care.

This has not helped Mr Modi’s standing with the Hindu religious establishment. At this year’s Kumbh Mela, a pilgrimage that is the world’s biggest public gathering, BJP flags and billboards proliferated along with boasts of a huge boost in public spending to organise the six-yearly event. Yet several senior religious figures seemed unhappy. “They have been talking of nothing but Ram, Ram all these years, and now they ask us to stop?” mutters Swaroopanand Saraswati, the head of two of Hinduism’s most prestigious monasteries, as a pair of young acolytes flick yak-tail fly whisks. In a nearby encampment, another high-ranking holy man, his forehead streaked with turmeric, complains that the BJP and RSS are trying to hijack the faith while doing little for issues such as protecting the sacred Ganges river.

Secular foes of Hindutva, however, fear Mr Modi has gone too far. “The battle for a secular India is already lost,” says Mujibur Rehman, a political scientist at Jamia Milia University. Mr Rehman does not blame Mr Modi but sees an acceleration under BJP rule of a slow disempowering of India’s non-Hindu minorities. “When the BJP bans cow slaughter, no opposition party makes the argument that this destroys Muslim livelihoods.” Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a columnist and head of Ashoka University, also sees many signs of Hindutva’s “hegemonic arrival”. One clue is that the BJP’s main opponent, the Congress party, has largely dropped talk of secularism. Since winning the state of Madhya Pradesh in December, Congress has outdone the BJP in cow protection, budgeting millions to build shelters for retired cattle. Its national leader, Rahul Gandhi, now punctiliously visits temples. “He is trying to show that he is no longer ‘embarrassed’ by his Hinduism, and this is a huge thing since the core RSS belief is that the secular state has left Hindus culturally marginalised,” says Mr Mehta.

Hindu the right thing

This may be seen as a healthy shaking off of colonial legacies. Yet what worries Indian liberals is where Hindutva strays into xenophobia and intolerance of dissent. By repeating a mantra of victimhood it constructs a world full of enemies, making it easy to conflate Pakistani jihadists with protesters in Kashmir or simply critics of Mr Modi. A window sticker now common on cars, showing the monkey god Hanuman with an angry orange face, is disturbing as it seems to respond to a threat which, in a country that is overwhelmingly Hindu and proudly so, is hard to perceive. That sense of threat, says Mr Mehta, is what binds the RSS: “Take that away and the whole project disappears.”

Mr Gandhi vows that, if elected, he will remove people with RSS links from the bureaucracy. But its devotees have risen organically within the system. “They are judges, they are professors, they went from RSS-run crammers to pass the civil-service exam, or RSS military academies into the army,” says Pragya Tiwari, author of a forthcoming book on the RSS. “These people aren’t going anywhere.”

Obstacles to the RSS agenda may come more from within the group, and from outside politics. The size of the family means it is also cumbersome and quarrelsome. And its increased exposure to politics has opened new internal frictions and exposed it to greater scrutiny. “Before, people were lulled, they wanted to believe these guys were innocuous, they didn’t really understand what was at stake,” says Ms Tiwari. Now, there is a stronger will to push back.

Yet there seems limited conviction among Indian liberals that the Hindutva tide can be stemmed. Outside big cities, the roots of secular, inclusive India remain shallow. This lack of a strong and attractive liberal alternative matters more in the long term than the coming vote. Mr Mehta’s prognosis: “Unless there is a massive repudiation, their staying power will be much stronger after the election.”

This article appeared in the Briefing section of the print edition of The Economist under the headline “Orange evolution”

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia