We were told that the generosity of the rich would make up for cuts to government services. But those at the top are increasingly using dubious “charitable” ventures as vehicles for profit and influence.

Everything feels like a scam for the rich these days, so why should private charity be any different? While lower-income Americans have tended to be disproportionately generous when giving away what they earn, a new report sounds the alarm about charity becoming more and more of a rich person’s game — and, worse than that, an investment vehicle that only strengthens the position of the very wealthiest.

According to the Institute for Policy Studies’ report Gilded Giving 2022: How Wealth Inequality Distorts Philanthropy and Imperils Democracy, charitable giving is more dominated than ever by those at the top of the income and wealth pyramid. While households making $200,000 or more were responsible for just 23 percent of itemized contributions in 1993, twenty-six years later, this figure had climbed to 67 percent. Over the same period, households earning more than $1 million, the top 1 percent of income earners, saw their share of giving grow from 10 to 40 percent.

As a result, donations tend to be bigger now, too. While gifts of $1 million or more from individual donors totalled only $2.3 billion in 2011, states the report, ten years later that had gone up nearly fivefold to $10 billion. In fact, wealth inequality had climbed to such an extent over this period that even the threshold of how Giving USA, a foundation devoted to scrutinizing charitable giving, defined what counts as mega donations had skyrocketed: from $30 million to $450 million.

If you were hoping that at least all this charitable mega-giving sloshing around might make up for the steady erosion of tax revenue from the very top, you’ll be disappointed. Drawing on data from the Chronicle of Philanthropy’s 2022 list of the 50 top US philanthropists, IPS concluded that just shy of 80 percent of the $25 billion worth of donations over $1 million among that cohort went not to working charities — the institutions we usually think when we talk about charities, like the SPCA or Salvation Army — but to their own private foundations and donor-advised funds (DAFs).

But both of these entities are little more than vehicles for their donors’ influence and enrichment. The report points out that the foundations donors set up allows them to appoint themselves and anyone they know as trustees, a status that allows them to dip into the foundation’s “charitable” funds to take out loans or be compensated to the tune of potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars, compensation that counts as charitable disbursements — all while enjoying the tax benefits of charitable giving.

DAFs, meanwhile, have swiftly become among the most popular places to stash extreme wealth, effectively serving as charitable bank accounts that let a donor park their assets and even grow their value over time. Among their benefits are the ability to evade capital gains and other taxes as these assets accrue, a lack of transparency, and no legal requirement that any of the donated money actually get paid out, which is why investment banks like Morgan Stanley hawk it to their clients as a clever wealth management strategy.

It’s little wonder that each has ballooned in popularity over the past decades. From 1990 to 2020, the number of private foundations nearly quadrupled to 127,595, with much of that growth coming in the last ten years alone, states the report, while the value of assets they hold has jumped nearly 700 percent to an unimaginable $1.2 trillion. DAFs, meanwhile, grew fivefold between 2010 and 2020 to more than a million, while the donations that flowed to them grew more than 400 percent, to the point that they now control more than $160 billion in assets.

It’s not just that this is an enormous tax evasion scheme, and a massive hoard of wealth that the US public is deprived of as its physical and human infrastructure falls apart around it — though it is that. Annual payout rates for private foundations are little more than the 5 percent they’re legally forced to pay every year, and for the biggest ones, it tends to hover around this floor. A variety of figures exist for DAFs, ranging from a median of 3.1 percent in 2018 to nearly a third of DAFs paying out nothing at all, as cited in the report.

But the other, potentially more serious dilemma, as the authors point out, is the power and wealth this style of supposedly charitable giving bestows on its donors. The report points to the examples of the Walton Family Foundation, which has showered a variety of free-market, pro-tax-cutting think tanks with its riches, as well as Carl Icahn, the onetime billionaire Trump advisor who borrowed $119 million from his own foundation as part of an investment strategy, then poured his returns back into it.

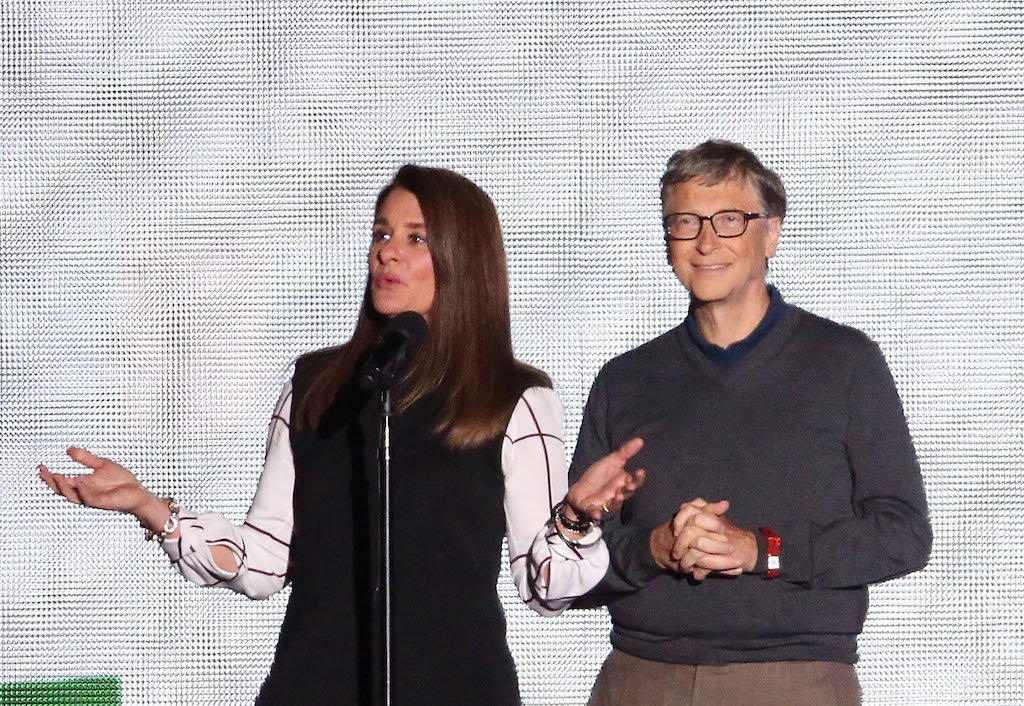

We might also think of the pernicious work of billionaire “charitable” institutions like the Sarah Scaife and Bradley Foundations, which have given copious amounts of money to anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant entities over the years. Or we might think of the way that Bill and Melinda Gates have used what is meant to be a “charitable” foundation to push for school privatization and pharmaceutical interests while also sneakily enriching themselves.

Dispiritingly, it’s not just that the ultrarich have more and more turned to dubious charitable giving to grow their wealth and power; it’s that those at the bottom of the pyramid have scaled back their donations. The share of US households giving to charity fell below 50 percent for the first time in the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy’s Philanthropy Panel Study’s twenty-year history, states the report, while individual donations as a share of disposable income had fallen to a twenty-six-year low in 2021.

According to the report, a drop in donations correlated with both the rate of labour force participation and home ownership, suggesting that rising economic hardship may be to blame. That’s bad news for working charities, which are not only still reeling like the rest of us from the ongoing economic disruptions the world’s experienced the past few years, but are more and more reliant on wealthy donors to keep the lights on, with the risk of falling under their sway and seeing their missions subverted.

The idea that the private philanthropy of the very richest will step in and make up for a systematically defunded public sector has always been a neoliberal myth. But as the IPS report shows, not only is the generosity of the 1 percent not enough to replace precious public services — it’s become just another way for them to grow their wealth and power.

This essay was originally published in Jacobin magazine.

Branko Marcetic is a Jacobin staff writer and the author of Yesterday’s Man: The Case Against Joe Biden. He lives in Chicago, Illinois.