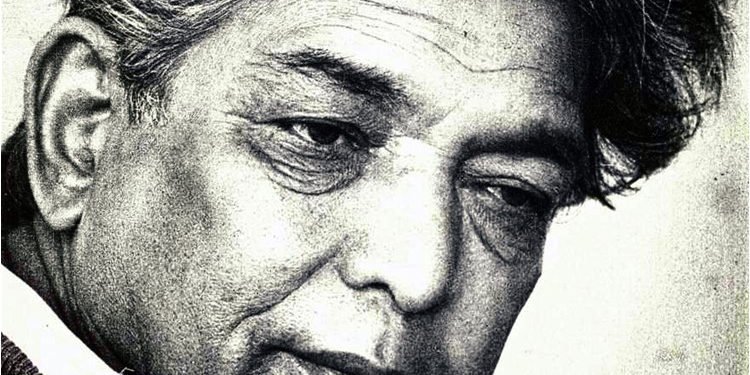

Raza Naeem on the politics and worldview contained in the work of Kaifi Azmi (1919–2002)

by Raza Naeem

“Stone Kaifi to death, the rulers cried

The Messiah? We do not know where he hides!”

Born Syed Athar Hussain Rizvi, a hundred years ago this year, Kaifi Azmi, who passed away into eternity seventeen years ago on the 10th of May earlier this month, was initially educated in Islamic seminaries, but eventually became a true adherent of Marxism, dedicating his life to the service of the Communist Party of India, and writing his most tortured work, Aavara Sajde (Vagabond Obeisances), when the CPI and CPM split in the 1960s.

Born Syed Athar Hussain Rizvi, a hundred years ago this year, Kaifi Azmi, who passed away into eternity seventeen years ago on the 10th of May earlier this month, was initially educated in Islamic seminaries, but eventually became a true adherent of Marxism, dedicating his life to the service of the Communist Party of India, and writing his most tortured work, Aavara Sajde (Vagabond Obeisances), when the CPI and CPM split in the 1960s.

In the last lines of his eponymous poem, he notes:

“One god after the other arrived”

He is well known for his proclamation: “I was born in enslaved India, have lived in independent secular India, and God willing, I will die in socialist India.” Alas, his last wish was not to come true; indeed, the year he died, and recent years even more so, were especially difficult even for secular India, thanks to the Gujarat pogroms. Kaifi’s death became a moment when people took it upon themselves to rededicate themselves to the idea of secularism.

Kaifi won many awards in his life, but was proudest of his Soviet Land Nehru Award. The Urdu Academy conferred on him the Millennium Award in 2001, and he was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Fellowship in 2002. His presence is well-represented on the web, and translations of his work, including the two most recent ones done by Rakhshanda Jalil and Sudeep Sen to commemorate the birth centenary, have been well received.

Kaifi’s oeuvre is not as vast as some of his other contemporaries, but it is varied and non-compromising on quality. For example, one of his poems Andeshe (Premonitions) is a poignant description of an ending relationship, and was adapted by Chetan Anand in the 1964 film Haqeeqat, picturized on soldiers presumed dead in the 1962 Indo-China war imagining their spouses grieving them.

Kaifi’s death became a moment when people took it upon themselves to rededicate themselves to the idea of secularism

“The soul itself is upset; it’s not merely the heart’s pain

The heart is all afire, agony is a refrain

I’m not sad that she forgot me and scrubbed memory’s stain

But she did it with tears and hurt – that is what I regret.

Resigned, her young expectations must have bowed their forehead

Her certitude must have sunk to resignation with dread

A pall of smoke might have set in, the earth turned on its head

When her first dream-nest she was forced to destroy and forget.

The heart must have narrated to her such a complex tale

That she would have held back her tears composed and calm, but pale

But when she burned my letters in a closed room with a wail

Every word must have floated up and made her eyes more wet.

Scared, she must have avoided each recriminating gaze

But in a hundred images, she may have seen my face

When she must have moved my picture from its familiar place

She would have found me everywhere, a painful silhouette.

An innocent tease may have led emotions to overflow

Her tentative and bashful smiles would have betrayed sorrow

But when she burst into tears at my name, don’t I know

Her head on her friend’s shoulder would have stayed, upset.

If friends insisted on making her up, combing her hair,

Her saddened beauty must have seemed so barren and bare

Her face would strike no lightning awhile in hearts debonair

It would not have regained colour for days, alas not yet.”

In another poem Makaan (House), Kaifi writes about construction workers and their role in the conquest of nature. In its un-self-conscious modernism, the poem extols the power of labour in achieving mastery over nature (through the use of walls, and cables of electricity), and is reminiscent of a similar poem by Majaz on the train Raat Aur Rail (The Night and the Train), albeit with a lot more anger on behalf of the dispossessed workers. To me, the poem depicts the ultimate potential failure of modernity from the point of view of the socialist: that it does not automatically ensure a jus and egalitarian society. Modernity sometimes fails the very subjects who were promised freedom from the feudal system they had laboured under in earlier eras. Kaifi ends with a call for collective action, which is a trope he was to deploy consistently in his work.

“A hot air blows tonight

It will be impossible to sleep on the pavement

Arise everyone! I will rise too. And you. And yourself too.

That a window may open in these very walls.

The earth had forever threatened to swallow us

Since we descended from trees and became human,

Neither these houses, nor their residents care to remember

All those days humanity spent in caves.

Once our arms learned the craft however, how could they tire?

Design after design took shape through our work.

And then we built the walls higher, higher and yet higher

Lovingly wrought an even greater beauty to the ceilings and doors

Storms used to extinguish the flames of our lamps

So we fixed stars made of electricity in our skies.

Once the palace was built, they hired a guard to keep us out

And we slept in the dirt, with our screaming craft

Our pulses pounding with exhaustion

Bearing the picture of that very palace in our tightly shut eyes

The day still melts on our heads like before

The night pierces our eyes with black arrows,

A hot air blows tonight

It will be impossible to sleep on the pavement

Arise everyone! I will rise to. And you. And yourself too

That a window may open in these very walls.”

I now want to turn our attention to another of Kaifi’s important poems, Iblees ki Majlis-e-Shoora: Doosra Ijlaas’ (Satan’s Congress: Second Session), inspired by the eponymous poem written by Muhammad Iqbal almost half a century earlier. In fact Kaifi’s poem was written in 1983, exactly a hundred years after the death of Karl Marx. This poem cannot be numbered among Kaifi’s classic poems, nevertheless it is very important for its contemporary significance and historic eloquence, reading the poem as we are 200 years after the birth of Karl Marx, and at a time when capitalism is in another crisis in its very centres in Europe and North America. Unlike Iqbal’s aforementioned poem, the Satan of the ‘Second Session’ is a reactionary character, who is the creator of imperialism, monarchy and fascism; and is witnessing the scene of his defeat with his own eyes. It does not matter whether this defeat is at the hands of socialism or Islam – or the revolutionary fusion of both. Following Iqbal’s poem, Kaifi’s poem indicates this situation.

Actually, Kaifi’s poem is not a response to Iqbal’s poem, but an expression of the prospects which are concealed within the womb of this historic epoch. Today a new compromise between the Islamic world and socialism is needed, which is of historic importance. For Kaifi, only socialism will end capitalism and monarchy; and the democratic and humanist traditions of Islam will assist it.

At one point he writes:

“The flood of peace clashing with the palaces of Washington

Cannot cross it alive, this paper lion”

Whereas the poem sensitively mentions, in passing, inter-socialist conflicts (between the USSR and Maoist China), it also does not shy away from sympathy with the Palestinian cause. The poem offers a stark commentary on how India had started moving away from its warm support for Palestine in Nehruvian India in favour of Israel while Kaifi was still alive:

“Nazis of the past are now Israel

Before whom, heads bowed, are the heirs of the Nile”

The poem also anticipates the growth of US imperialism (there are references to the US defeat in Vietnam), the rise of Arab petrodollars (following the defeat of Nasserism and the surrender of Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat at Camp David), rogue capitalism, and the perils of nuclear warfare – all of which we in South Asia are all-too-familiar with in the 21st century.

Kaifi’s poem is not a response to Iqbal’s poem, but an expression of the prospects which are concealed within the womb of this historic epoch

“Those who number dollars on the beads of their rosaries

Their beards like purses, making begging-bowls of their bellies”

Kaifi’s brief “Statement of Defence” at the beginning of the poem deserves to be quoted in full here to give a fuller measure of the man and his politics:

“By writing ‘Satan’s Congress (Second Session)’ I find myself in the witness-box of the accused and I am presenting my defense by seating my conscience on the chair of justice that whatever I say will be the truth and nothing but the truth. About 30-35 years ago when I had read Dr Iqbal’s famous poem ‘Satan’s Congress’ for the first time, I was influenced, as well as impressed by it. But afterwards when history did not follow the exact same pace which Satan had predicted, then the wish repeatedly arose that I should summon the second session of Satan’s Congress and narrate its tale. But for one I was so impressed by Iqbal’s tone and melody that I would not have the courage to lift the pen. Secondly, this hesitation too: lest I begin to be numbered among those Lucknow poets who wrote long poems in response to ‘Shikva’. I am grateful to (Ali Sardar) Jafri that he has clarified in his preface that this poem is not a response to Iqbal. This is the truth, too. I see, and like me, so does the world, that socialism which was not deemed even worthy of attention by Iqbal’s Satan and whose antidote he has seen in fascism, today that philosophy of life is victoriously embracing the entire world of humanity in its wide arms. When fascism and Nazism were dealt a decisive defeat at the hands of socialism on end of the Second World War, then I and late Sahir (Ludhianvi) made a plan to write the second session of Satan’s Congress; but like many official plans, that plan remained merely on paper. But the manner in which there was a general massacre of Palestinian fighters in Beirut at that time shook up my conscience such that I indeed wrote up this poem. However much trust I have over my philosophy of life, had I had a similar trust over my art too, then this poem would have been written long ago, and there would not have been the need to present a defense.”

All his life, Kaifi Azmi remained a hopeful stormy petrel of socialism. And as he would gently condemn the naysayers,

“Those who watch the storm from afar

For them, the storm is both here and there”

This feature was first published in The Friday Times, May 31, 2019.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore. He is the recipient of the 2013-2014 Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship in the UK for his translation and interpretive work on Saadat Hasan Manto’s essays. His most recent work is a contribution to the edited volume ‘Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry’ (Niyogi Books, 2019).He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore. He is the recipient of the 2013-2014 Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship in the UK for his translation and interpretive work on Saadat Hasan Manto’s essays. His most recent work is a contribution to the edited volume ‘Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry’ (Niyogi Books, 2019).He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia