By Anwar Iqbal

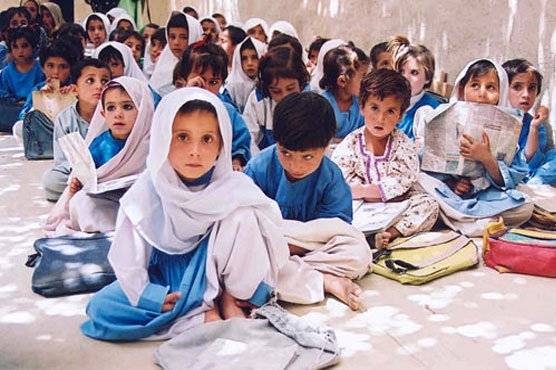

WASHINGTON: Many children in Pakistan cannot read a sentence even after years in school, says a new study of the country’s education system, arguing that the focus should now shift from quantity to quality.

The study — “Pakistan’s Education Crisis: The Real Story,” by a Wilson Centre global fellow Nadia Naviwala — seeks to explain how Pakistan’s education crisis has been misdiagnosed.

The author points out that there are 17 million primary aged children who go to school in Pakistan, compared to five million who do not. The main problem, according to her, is that those who do go to school are not learning much. Many “cannot read a sentence after years in school,” says Ms Naviwala. She notes that this is a global problem but it “is only worse in Pakistan because of the use of foreign languages in education”.

She also quotes from a British Council survey which shows that 94 per cent of English-medium private school teachers in Punjab do not speak English.

Author suggests primary schools should have female teachers only

Urging the country’s leaders — such as Prime Minister Imran Khan — to encourage education in mother tongues, Ms Naviwala says that donors also need to move away from the programmes “driven by headlines in foreign capitals”.

“If there is one education emergency (in Pakistan), then it is not the 5 million out-of-school children, but rather the 17 million children who are in school and learning nothing,” she warns.

The author suggests:

The ability of children in school to read with comprehension should be compared on a year-to-year basis.

The skill of reading must be taught (a) in school, (b) through large- scale alternative education programmes for older out-of-school children where schools do not function, and (c) through adult literacy programmes.

The curriculum needs to be simplified and brought down to the level of the child. Early grade and primary education must embrace the mother tongue, with textbooks in those languages.

Higher education should embrace multilingualism. The current insistence on English excludes the majority, despite their level of intelligence, and fuels plagiarism because students and professors cannot produce original scholarship in English.

There is an insistence on English for science, but allowing students to express themselves in the language they know will improve the quality of scholarship in the social sciences.

The highest priority should be given to having all-female teachers in primary schools. This is more important than all-girls schools — there appears to be more tolerance for co-ed schooling than people think given that many girls and boys schools are co-ed, and especially at the primary level.

The crisis of out-of-school children is a crisis of youth aged 10 to 16. Of Pakistan’s now- 23 million broken promises, 18 million belong to this age group. Pakistan needs a large-scale education programme for them. Higher secondary education (grades 11 and 12) and degree colleges (two-year programmes for years 13 and 14) need the kind of attention that has been given to primary school and university.

Teachers must be taken out of elections. The Election Commission of Pakistan needs to figure out a different work force.

The courts must stop converting teachers and staff hired on contracts into permanent government employees with pensions because there is a belief that the state owes people jobs. This feeds and reflects a culture of corruption, through non-performance, in the public education system.

Primary schools should be co-educational to increase access for all children and narrow the gender gap. This is key in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and tribal areas, where the government and donors are expanding girls’ primary schools. Even in rural areas in erstwhile Fata, half of private schools are co-educational.

Teachers should be restricted to working in the areas they are hired from — preferably within walking distance to schools, or areas accessible by local transport if teachers are not available in the immediate community.

The power over posting and transferring teachers should be taken away from the education secretary and politicians.

To decentralise the system, district education authorities, hired from the private sector on contracts and on merit, should have the highest decision-making powers, not the central bureaucracy in cities.

Courtesy: Dawn

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia