Tajikistan has a rich heritage of exquisite wood carvings. Dr Larisa Dodkhudoeva from the Institute of History, Archeology, and Ethnography named after Donish talks about the origins of this art and how it transformed into a professional craft.

by Lolisanam Ulugova

The art of wood carving among Tajiks, along with many peoples of Central Asia, originated in an immemorial time, when people began using wood for various buildings.

When constructing they realized that trees could be decorated with various ornaments that could significantly enrich the design of rooms (canopy, windows, etc.).

Masters mainly used species such as plane trees, mulberry, juniper, walnut, and others. Hard grades were used for the manufacturing of architectural details pillars (sutoon), poles, doors (dar), shutters (daricha), gates (darvoza), gratings (panjara), rostrums (mimbara) in mosques and madrassas (religious school), as well as for other handicraft works.

Larisa Dodkhudoeva is a native of Dushanbe, Tajikistan. She is a graduate of I. Repin Institute of Architecture, Painting and Sculpture of Academy of Fine arts in St. Petersburg. Larisa is the Head of the Ethnographic Department at A. Donish Institute of History, Archaeology, Ethnography under Tajikistan National Academy of sciences. She published 30 monographs, albums, and numerous scientific articles on Persian miniature painting, crafts and contemporary art of Tajikistan in her country and abroad.

Wood carving (kandakory) in Tajikistan is a diverse art and has several types of techniques: relief cutting (clear-cut), flat cutting, deep cutting, double-sided cutting, and facing (cladding) cutting. Large geometric shapes, circles, and other motifs with streamlined shapes are trimmed with a roller. Semi-square lines in cross-sections are for border ornamentation.

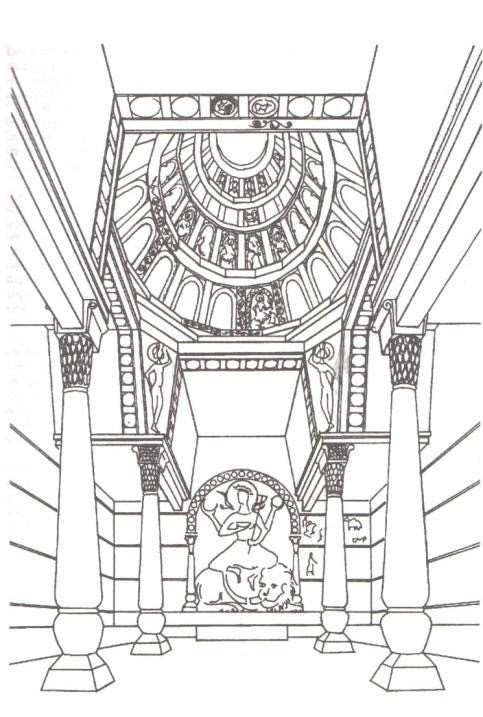

Fragment of a niche in the mosque found in Ayni district, Sugd province, State National Museum (photo by Zaur Dahte)

Fragment of a niche in the mosque found in Ayni district, Sugd province, State National Museum (photo by Zaur Dahte)

There are constructions from the 7th to the centuries AD that has been found in the castle of Mount Mug in Pargar. The carvings are diverse and are distinguished by the high technique of processing natural materials, including the usage of dagger sheaths, arrow shafts, buttons, shovels, dishes, hoops and others. Another way this craft was practiced was by making wickerworks (sabadbofi).

Wicker baskets with lids, covered with dyed leather and distinguished by their clear form and meticulous workmanship, have been discovered in the castle on Mount Mug. Before weaving, the rods were subjected to a special treatment, after which they acquired a square cross-section.

The masters of Penjikent even made domes from wood, covered with carvings depicting gods, luminaries, and overlapping various buildings. There were halls housing caryatids along the walls with carved friezes (depicting deities, hunters, dancers, a winged horse, a duel of warriors, etc.), made with the technique of deep carving. Many of these monuments have been preserved in buildings that have been destroyed by fire.

The oldest centres for the artistic processing of wood were in Bukhara, Samarkand, Istaravshan, Khujand, Isfara, Penjikent, and villages in the upper reaches such as Zarafshan, Yagnob and others. During the Middle Ages (specifically the 5th to 8th centuries) cities such as Penjikent, the Mug Castle, Hisorak, and Gardani Hisor were famous for their magnificent examples of carvings on the “Kandakori” tree. In the mountainous regions of Upper Zarafshan (Kuhistan) people never had a tradition of decorating interiors with murals and instead decorated them with wooden details.

Another example of wood carving was displayed at the Mausoleum of Hazarati Shah (Langar Bobo) in Chorku (near Isfara), in the oldest wooden building in Central Asia (dating back to the 9th century). This is a masterpiece of wooden architecture and carving in the form of an ivan (terrace) with carved and sculptural decoration, the purpose of which has not yet been determined.

Wood fragment from Matchoi Kuhiston Mosque (photo by Zaur Dahte)

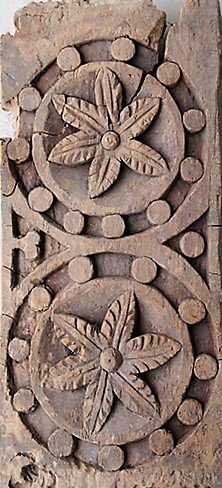

Flower petal motif wood fragment from Penjikent

Musical instruments made of rare wood were one of the important areas of the craft. In Ustrushan, the remains of musical instruments are found dating back from the 5th to 9th centuries AD. In Badakhshan (at the Zumudg burial ground), a harp from poplar, lute, and dutar, were found all dating back to the 5th to 6th centuries AD.

Masters from Kulyab, Vanj, Garm, Gissar, Shaartuz-made caskets, clubs, curly back chairs, printed stamps, and wooden shoes with three heels (kushichubin) all made of walnut wood for the winter. Their decor included ancient relic motifs.

The main motifs (rhombus, circle, cross, zigzag, spiral, triangles, hooked squares, rectangles, stepped octagons, etc.), which decorate most ancient archetypes, are found in rock paintings and are made from archaeological material of the Bronze Age. Initially, the symbols served not as decoration, but as an integral part of ancient rituals and ceremonies. All traditional symbols begin to “work,” but only during rituals. Without it, an object with symbolic motives remains just a functional thing.

In fact, local craftsmen have been custodians and translators of certain meanings of ethnic culture. The preservation of sacred signs and their endless repetition in the works of craftswomen is emotionally very significant for the local society, although they aren’t always easily considered by its representatives.

However, their presence is in products that are widely used in everyday life, and their never-ending repetition and copying by craftswomen are designed for long-term memory. The repetition and transmission of sacred symbols are passed down from one generation to another. In fact, artisans broadcast the collective values of their traditional culture and those in which they grew up or understand.

One of the outstanding monuments of the Samanid era is the U-shaped mihrab from Iskodarhas which has been decorated with ribbons of a geometric pattern with swastikas, which was a common phenomenon in the decoration of early cult niches of Islam. The entire structure is filled with foliage ornamentation, through three-dimensional carvings, covering individual elements that are so perfect that this exquisite, abstract plastic cannot be found elsewhere in Islamic art.

From the 18th to 19th centuries, Zerafshan craftsmen continued making columns and doors, but in addition, made dishes, measures for grain, shoe stocks, pencil cases, combs, panels, carved boards (kalyba) stamps for stuffing fabrics, and chests. As noted by A.S. Davydov, masters in Upper Zarafshan had wide profiles, they could work with everything made of wood in their village and its surroundings. Even oil presses were made by woodworkers (chubkor).

Furthermore, the woodcutters made different types of jewellery boxes (durch) and chests (hamm) without ornamental decor, which were intended for storing flat cakes in Zarafshon.

Today, for the master Yusuf Kaumov from the village of Ruknobod, this type of product is the main household craft. Master Dilmurod Khomidov from the village of Kuhdaman makes mainly wooden boxes. In today’s Penjikent, the family dynasties of woodworkers of the Toshbekovs and Ravshanovs are engaged in the manufacturing of cradles (gakhvor), wooden shovels, sieves (galber), saddles (elakzin), spoons (chumcha), baskets (sabad), bird cages (ќafas), vessels of various kinds for grinding dough, and etc.

The weaving of baskets (sabadbofi) has developed everywhere in the Zerafshan valley. In the village of Ozodagon of the Jamoat Khurmi, the Narzulloev family has been engaged in wooden manufacture, and their members weave baskets for flat cakes (nonbardorak), with various types of trays (nongirak) and large hanging baskets for milk products, birdcages, etc. Courtesy: Voices on Central Asia

Lolisanam has been an art manager in Tajikistan since 2000. She has contributed to writing and producing the nation’s first 3-D animation film, designed to promote awareness of environmental issues among children. She holds a Master’s degree from the University of Turin, Italy and an undergraduate degree in Russian Language and Literature. She was a Global Cultural Fellow at the Institute for International Cultural Relations at the University of Edinburgh and participated in the Central Asian-Azerbaijan (CAAFP) fellowship program at the George Washington University at Elliott School of International Affairs for Fall 2019.

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia