In his two-part article, Zameer Abbas touches upon the other sides of Juan Ellia’s personality as a progressive thinker, biographer, translator, and historian which have been overshadowed by his poetry.

Zameer Abbas

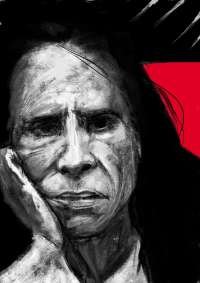

The popularity of Jaun Elia (1931-2002) as a poet has risen in recent times. Despite his intellectual versatility, he was not as well-known during his lifetime as he is today mainly because he resisted getting his works published for a long time. However, the newly increased interest in Jaun Elia has overly been focused on his poetry; mostly the rhythmic, catchy and mesmerising verses recited by him in Mushairas.

The popularity of Jaun Elia (1931-2002) as a poet has risen in recent times. Despite his intellectual versatility, he was not as well-known during his lifetime as he is today mainly because he resisted getting his works published for a long time. However, the newly increased interest in Jaun Elia has overly been focused on his poetry; mostly the rhythmic, catchy and mesmerising verses recited by him in Mushairas.

That Jaun Elia was a bohemian poet is evident from a bare reading of his sample kalaam (poetry), now available in print, e-books and of late in innumerable audio and video clips on YouTube. This easy access has spread his poetry among the public at large, especially the youth, who upload and share it on social media. His online fans are based all around the world and not just Pakistan. Nonetheless, this poetry-centric approach to reading and understanding non-conformist poet has eclipsed his works in prose. Most, if not all, of the new Jaun enthusiasts, consider him a poet only.

Given the richness of his thought in both poetry and prose, consideration of Jaun only a poet doesn’t do justice to his ingenuity. On deeper reading, he comes out as an individual with many personas: all fickle and stable at the same time. This contradiction in terms was a distinctive part of his personality as narrated by dozens of his friends, contemporaries, close relatives, confidants, and admirers. This two part series will touch upon the other Jaun Elia, as opposed to the popularly known poet.

Jaun could not become only a poet simply because his household and social surroundings were diverse intellectual breeding grounds, poetry a small part of it. In his own words: “the time around my birth was marked by discussions around Aristotle on the one hand and on Heraclitus and Democritus on the other. Amroha was alive with debates on whether God existed”. Such debates are unimaginable in today’s increasingly intolerant world. During his lifetime, Jaun wrote about many things ranging from his role as an actor in the drama club he founded to his loss of conviction in the cherished beliefs he inherited. His poetry is a panorama on philosophy, nihilism, love, lust, nostalgia, Muslim irrationality, criticism of society, existential angst, promiscuity, communist idealism and above all, his guilt about not being able to live as he wished to, perhaps like all the great artists who dream a different world other than the one they live in. However, this didn’t prevent Jaun from thoughtfully writing about these topics. If his poetry made brief references to philosophy, his prose unfolded the theme and explained it in everyday terms. If he made fun of a religious bigot in a stanza, his essays expanded with a historical perspective.

Let us consider the unique observations and derivations of Jaun Elia on Islamic rationality; the tradition that emphasizes a greater role for human reason in understanding Islamic injunctions in the Quran and Sunnah. Like many scholars of Islam who lament the loss of intellectualism and closing of the Muslim mind, Jaun emphasized free inquiry and philosophical discussions as the way forward.

He was critical of the religious fundamentalists who, in his view, had always conspired to stifle fresh thinking and punished those who had dared to challenge their parochial views. He called such narrow-minded clerics “zulmatoon kay murabbbi”, the mentors of darkness, violently opposed to the enlightenment of mind. The metaphors he used for religious bigots and retrogressive Muslim leaders in society are terse, derisive, meaningful and expressive especially in the poem ‘Shehr-e-Ashoob’in ‘Shaayad’, his first collection of poetry. But Jaun being Jaun, went beyond criticising them and reminded how a culture of debate and inquiry marked a certain period of Muslim history until traditionalist thinking took over. His choice to be a student of both Deobandi and Shia teachers showed his open-mindedness when it came to accepting sectarian differences. Such cross-sect education is unthinkable today, generally for all the Muslims and particularly for those who attend religious schools or seminaries. This is not to deny sectarian differences during Jaun’s time, but his magnanimity to rise above those differences, as is expected of any scholar.

Jaun’s deep knowledge of both Arabic and Persian, the languages of almost all classic Muslim scholars, enabled him to comment on many of the topics rarely discussed by later day scholars. A cursory look at the books/treatises he rendered in Urdu for Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Karachi, shows the depth of his understanding of the languages of Islam. The titles included “Hasan Bin Sabah”, “Analytics”, “Geometry”, “Ismailism in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq”, “Rasail-e-Ikhwanus-Safa” and many more. Unfortunately, most of the listed works are not available for public reference.

Jaun went beyond a mere translation and subjected these scholarly thoughts to critical interpretation in Urdu, his mother-tongue and lingua franca of the Muslims of the South Asian Subcontinent, making the undiscussed Islamic thoughts publicly available. His discursive understanding and commentary on philosophers like George Berkeley, John Stuart Mill, David Hume, Avicenna, Ghazali etc., remains unmatched in modern Urdu literature.

Jaun would have appreciated what Robert R. Reilly, a senior fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council, has argued in his groundbreaking book, “The Closing of the Muslim Mind: How Intellectual Suicide Created the Modern Islamist Crisis”. Reilly argues that the abandonment of philosophy and logic has triggered the Muslim decline. This theme has been taken up by Jaun in many of his essays and stanzas. The “unthought”, as the Algerian-French scholar and thinker Muhammad Arkoun, put it, in Muslim psyche has been underlined by many other reformist scholars of past and present like professor Fazlur Rehman, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi, Maulana Wahiduddin and Fatima Mernissi, to name a few, to overcome the limitations of a purely descriptive, narrative and chronological treatment of history and recommends a critical analysis of the entire development of Muslim thought.

Jaun’s recipe for the revival of Muslim thought reiterates opening of mind for new thoughts and a rationalistic re-interpretation of the scripture as the Mu’tazila scholars of 8th to the 10th centuries had taught. Controversial as it may seem, Jaun considered Mu’tazila thinkers to be “always unique in that they protected and revived the oldest intellectual heritage left behind by Semitic thinkers at a time when Islamic history was dominated and defined by politics alone; they introduced Hellenic and Roman modes of thinking to Muslim circles through an organised movement; (ideas which were) only discussed in the premises of the shrines of “Antakya and Alexandria”. He seemed to agree with what Fazlur Rehman called the “intellectual suicide” of Muslims because “(they) had deprived themselves of philosophy and thus fell in deprivation of fresh ideas”. Jaun praised the Abbasid caliphs who made Mu’tazila ideology “the state philosophy”.

In short, Jaun was more than a poet. His ideas about the revival of rationality in Islamic thought resonate with many modern scholars. I will briefly discuss his distinctive views on philosophy in the next piece.

Zameer Abbas is a freelance writer based in Gilgit. He tweets @zameer_abbas

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia