Every ideology, religion and worldview contains seeds of discontent within. The Enlightenment brought about a change in every sphere of life. But like any other transformation, it also sowed the seeds of discontent.

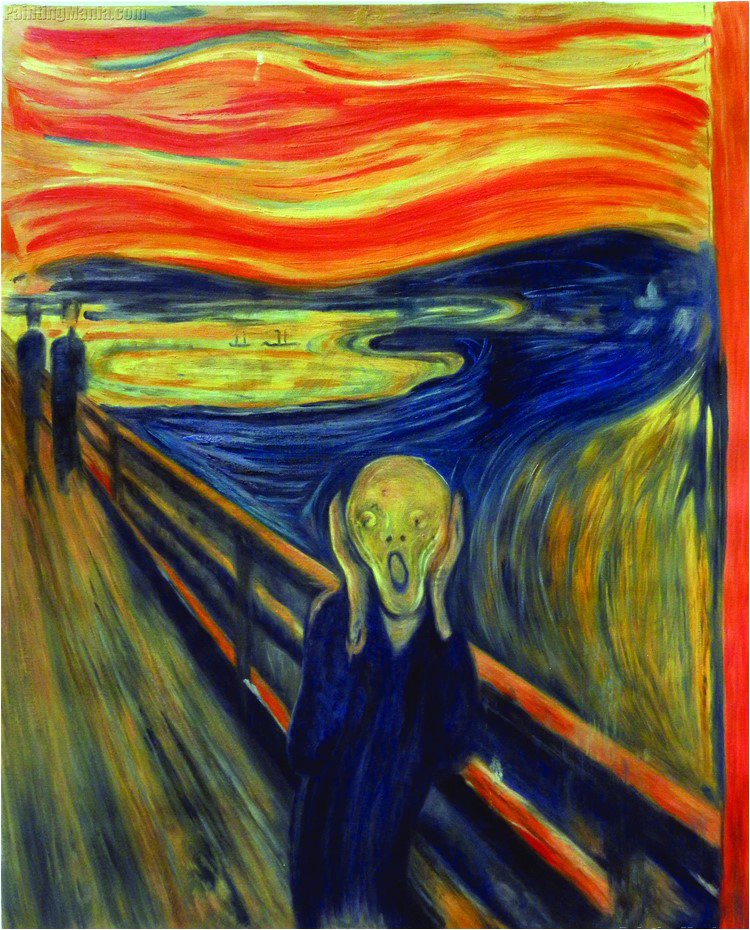

After disenchanting the world it had, in a manner of speaking, thrown the individual into the world. Bereft of old certainties, human individuals now found themselves in an indifferent universe. This has given birth to what Max Weber calls “metaphysical pathos”. The condition of individual in modernity is like a child screaming in terror after separating from his parent in an alien crowd. This existential scenario is well captured by Edvard Munch in his famous painting “The Scream”. When the whole world was euphoric about modernity, Max Weber warned humanity of the “iron cage” of rationalization whereby the individual becomes a prisoner of technological efficiency, bureaucratic apparatus and rational calculation. This is what happened in most of the twentieth century. Under the influence of the calculative rationality and secular teleology of modernity, the emancipatory zeal of the Enlightenment has been, for some, transformed into controlling and subjugating force.

The twentieth century presents the inexplicable paradoxes of the Enlightenment project. It was a century crowded with rationalists, scientists, philosophers, thinkers, artists and geniuses, yet it is the century that witnessed world wars, genocides, ecological disasters, gulags, unprecedented tyrants, nuclear bombs, environmental degradation, racism and poverty. In the case of modern bloodshed and mayhem, it is not some barbarians from pastures and mountains who descended upon civilization, but the new man created in the image of the ideals of the Enlightenment to serve modernity. The angel of history would have been aghast to see the coterminous existence of deadly concentration camps and universities where the best minds of the world worked. Since modern humans were under the epistemic, bureaucratic and technological spell of instrumental rationality, they could not pay heed to the supplications of non-instrumental reason.

It is to draw our attention towards the barbaric facets of the Enlightenment that German philosophers of critical theory Theodor Adorno and Max Horkhiemer wrote their seminal work The Dialectics of Enlightenment. They exposed the destructive tendencies within modern secular societies. According to Adorno and Horkhiemer reason has become irrational. Lamenting the degeneration of ideas of the Enlightenment, they note,

Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. Yet the wholly enlightened earth radiates under the sign of disaster triumphant.”

After serving humanity for the last 400 years, the project of modernity is in crisis now – not because of the growing intellectual strength of its opponents, but because of its own contradictions and dogmatism

Taking cue from their critique of the Enlightenment, one can find a possible answer to the question: was the Enlightenment universal?

It has to great extent become universal for the reason that the emergence of its ideas coincided with European military and economic expansion. The combination of the appeal of emancipatory ideas from the Enlightenment to non-Western societies and control over colonized societies helped expanded modernity into alien contexts. The process was similar to how modern jihadism went global because of revolution in information and communication technology. Also, this has contributed to emergence of multiple modernities in non-Western contexts.

After serving humanity for the last 400 years, the project of modernity is in crisis now – not because of the growing intellectual strength of its opponents, but because of its own contradictions and dogmatism. Over the time its reason has become ossified, though it is not fossilized as religion.

The modern meta-stories of socialism and liberalism are a part of the big story provided to us by modernity. Contrary to the dominant view of treating the meta-narratives of modernity and its ideologies of socialism and liberalism as antithetical to religion, they can be counted as parts of the post-axial age religions. John Hick in his book An Interpretation of Religion: Human Responses to the Transcendent finds elective affinities of the secular “faith” of Marxism with world religions. Hick declares Marxism “as a fairly distant cousin of such movements as Christianity and Islam, sharing some of their characteristics (such as a comprehensive world-view, with scriptures, eschatology, saints and a total moral claim) while lacking others (such as belief in a transcendent divine reality”. Similarly, French secularism is in the process of becoming post-religious religion.

Today we are witnessing disintegration of the universality of enlightenment. Almost one and half century ago, Nietzsche said that the whole millennium is breaking within him. He claimed, “I swear to you, we shall have the whole world in convulsions.”

Today we are living in great convulsions and disruptions where post-normal times and post-truth have become the norm. These changes are brought about not by humans but by the technologies invented by humans. The digital and infotech revolution influences our thoughts more than the ideas of the previous millennium including the Enlightenment. Infotechnology and biotechnology are already changing the order of things and ways of seeing by rendering solid space irrelevant and connecting people from heterogeneous backgrounds in networks to create new identities and solidarities.

Nietzsche’s prognosis is coming true. A few months before his death, Stephen Hawking expressed his fears about the end of humans because of the development of infotech and biotech. He proclaimed, “The genie is out of the bottle. I fear that AI may replace humans altogether”.

To understand the new configuration of human societies and cognitive mechanisms, we need another set of ideas and vocabulary. So far we have not succeeded in creating a vocabulary to explain reality in a post-human age. Today, the process of change exceeds the comprehension of our existing conceptual frameworks: we employ the vocabulary of the last millennium to explain an emerging reality whose contours are still not clear.

Walter Benjamin in his essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History” imaginatively captures the scenario of the fragmentation of a holistic worldview in his exquisite prose. He writes,

“This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.”

And so it is that today we are at a point in history where all previous outlooks including the Enlightenment are disintegrating. This is not to say that whatever we have learnt and experienced will disappear. Whatever new we experience, it takes a part of our previous self away from us to make room for itself within us. We have taken a miniscule part of the Enlightenment and it will remain part of our cognitive structure.

Although the digital age is causing disintegration of solid spaces and solidarities, it is helping in forming a new “dialectical conversation” through the social semiotics of a network society. We may enter into a new digital age but without the light of knowledge and an enlightened mindset.

The ossified mind and its cyclical thinking has turned the most enlightened ideas into dark prison houses. Ironically, it is the very proponents who have turned the Enlightenment into what it has become. Even when we accepted certain ideas of the Enlightenment and modernity, we stick to them as eternal truths. In the state of unthinking fidelity with ideas we have forgotten the essential lesson with which the Enlightenment itself inaugurated a new age.

Our thinking has become ossified because we are fixated with the idea that ideas are immutable and we fear both a rupture in continuity and the presence of continuity in rupture. Hence, stagnancy prevails in every domain of life and thought.

Jaun Elia has rightly declared us to be a nation that is scavenging on the mental feast of others for the last one thousand years. This metaphor encapsulates our mental state today.

The is the last instalment of a two-part article published in The Friday Times last month.

Aziz Ali Dad is a social scientist with a background in philosophy and social science. Email: azizalidad@gmail.com

Aziz Ali Dad is a social scientist with a background in philosophy and social science. Email: azizalidad@gmail.com