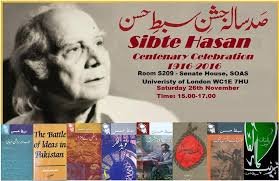

Raza Naeem on the enduring appeal of Sibte Hasan’s ‘Mazi Ke Mazar’, 50 years after it was written

by Raza Naeem

In our part of the world, the life of books is too short – not unlike an untimely death in infancy. It is a small mercy if a book manages to live for four or five years, but it is heartening to note that prominent Marxist intellectual Syed Sibte Hasan’s book Mazi Ke Mazar (Tombs of Times Past), which celebrated its golden jubilee earlier this week on the 21st of August, has now gone into its 19th reprint; proving that there is still a spark of life remaining in this work – and that the connoisseurs are still in pursuit of it.

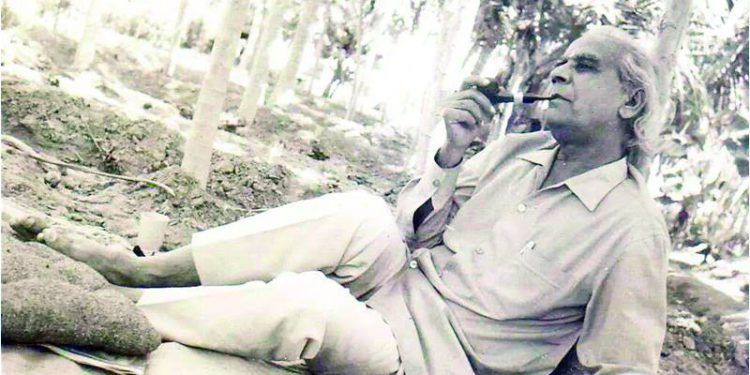

Sibte Hasan (1916-1986) was a very well-read man. He had not only studied the classic and modern literature of Urdu, Persian, and English but also had deep insights into economics, sociology and political science. He had indeed been trained in political science and had obtained an MA degree in this subject from Columbia University in New York in the United States (It was known as International Relations at Columbia). Another branch of knowledge which opened up new vistas of perception in his writings is anthropology. In Pakistan, the subject of cultural anthropology is, to a great extent, unpopular and underdeveloped; although in the developed nations of the world this social science has become one of the most popular subjects.

Sibte Hasan (1916-1986) was a very well-read man. He had not only studied the classic and modern literature of Urdu, Persian, and English but also had deep insights into economics, sociology and political science. He had indeed been trained in political science and had obtained an MA degree in this subject from Columbia University in New York in the United States (It was known as International Relations at Columbia). Another branch of knowledge which opened up new vistas of perception in his writings is anthropology. In Pakistan, the subject of cultural anthropology is, to a great extent, unpopular and underdeveloped; although in the developed nations of the world this social science has become one of the most popular subjects.

Sibte was especially enthusiastic about anthropology. The subject of Mazi Ke Mazar, indeed, is anthropology. It is one of his most important books and like his other books, the effects of Marxist thought are very clearly evident Mesopotamian civilization (in modern-day Iraq), also known as the civilization of the Valley of the Tigris and the Euphrates, has been studied in the light of Marxist principles of history. The subject of this book is basically the beliefs about the creation of the universe which were prevalent, especially in Mesopotamia and generally among the ancient Egyptians, Chinese, Aryans, and Canaanites. One way of studying beliefs and thoughts is to imagine them to be fixed in their essence and to deem the material conditions and particulars of society to be the result and manifestation of the same. But Marxism presents an entirely different ideology as opposed to this idea-worship. In the history of thought, the ideology of Marx and Engels carries the status of a revolutionary turn in its place: that the consciousness of an individual is neither the result of their social existence nor their exercise of reason. In other words, life is not determined by consciousness – but rather consciousness is determined by life. In the light of this totality, human history is really neither determined by the ideologies of philosophers and sages or by the ideas of a few people in a society,-nor is its journey dependent upon such things. Human history is really the history of social relations and these themselves are determined by productive forces: such as the Marxian perspective on the study of history.

Sibte was especially enthusiastic about anthropology. The subject of Mazi Ke Mazar, indeed, is anthropology

Mazi Ke Mazar is a book in which a whole ocean of knowledge and wisdom has been enclosed. Its importance can be gauged from the fact that precious little had been written on such a topic in Urdu prior to its publication and even if it was written, it was done in a very sketchy and pedagogic manner, or for the fulfillment of the needs of that time. It is perhaps the first book on anthropology in Urdu in which the tale of civilizational evolution has been told era by era, from the social life of ancient humans to the Tigris valley, the Indus valley, Syria and Iran, Central Asia, Egypt, the Arabian peninsula, etc. And it examines in what ways the beliefs, moral values, social customs, cultural manifestations, government, institutions were formed, and have changed and deteriorated; how the values of a matriarchal social system became different in meanings from a patriarchal society.

A brief extract from the first chapter of Mazi Ke Mazar follows:

“Nations disappear, but their effect remains on the way of society, industry, and craft. The manner of thinking and the character of literature and art; languages become dead but their words, proverbs, symbols, and metaphors enter new languages to become a part of them; the divinity of old beliefs comes to an end, but old idols remain in the sleeve of every new religion and every fold of the turban and tiara; civilizations vanish but the palaces of a new civilization keep dazzling with their marks and decorations

Five thousand years ago such a civilization arose in the valley of the Tigris and the Euphrates and before the eyes, it spread across the entire East. This civilization established its authority for 2,500 years from the Mediterranean to the Arabia Sea. Then the chants of the worshippers of Zoroaster arose in the fire temples of Persia, and the Achaemenid rulers raised the buildings of Iranian civilization over the rubble of Babylon and Nineveh. The civilizational current of the Tigris and the Euphrates mixed with the Iranian civilization and neither the religion of the land between the two rivers remained nor the language; but we cannot forget the favour which the inhabitants there have bestowed on the world by introducing Man to the knowledge and arts for the first time. The world’s oldest villages have been found in this same land between the two rivers; cultivation became a custom there for the first time indeed; the potter’s wheel was first invented there; the remains of the most ancient cities were found there; city-states were established for the first time in the same valley; and the first code of law was compiled on this very land. But the greatest feat of the ancient inhabitants is the invention of the art of writing. The first schools were also opened on the coasts of the Tigris and the Euphrates. The oldest libraries have also been available there and the oldest epics are also the creation of this area.”

The above-mentioned extract has been taken from the initial pages of Mazi Ke Mazar. Just from this extract the width and span of the book can be estimated. So much information has indeed been put together on various aspects of life in a special era and area; the potter’s wheel, the remains of ancient cities, the advent of the first city-states, the compilation of the first code of law, the invention of the art of writing, the style of libraries and schools, etc are references which accompany the reader everywhere. And then the style of narration is so light and flowing that the subject just opens up: sentence by sentence, line by line. There is neither a difficult word anywhere neither an unfamiliar term and then the mention of the display of contemporary life has made the expression attractive to the attention. This is not a discussion of the inconceivable events and happenings of the past, rather the accessories of contemporary life have been discovered, so that the story of an era by era evolution should come forward, completely. The paths to reason are opened up in front of the reader with the help of analyses and explanations of the various ideologies of creation and evolution drawn up in mutual opposition; a story of the effects which economic and social changes have on beliefs, thoughts, and values from era to era is also present. The manner in which lost links have been discovered between the remains of a bygone age; as well as how an attempt has been made to understand the collective mood and conditions of that age in relation to the literature and arts of different eras, areas, and generations – these have created further depth in Sibte’s style.

The wish to understand the social situation of a particular era in the mirror of ancient epics or the method of discovering collective hopes became a particular quality of Sibte Hasan’s writing; which imparted a freshness to the subject matter. Otherwise, the pessimism which a topic comprising thousands of years contains within might have been susceptible to creating a colourlessness in the style of expression.

For example, Sibte has translated the versified epic of Gilgamesh with extraordinary cleverness. Indeed this – the world’s first epic – is both long and versified. This is the epic of ancient Iraq of 3000 BC, whose hero is Gilgamesh. Sibte Hasan writes that in the semi-mythical and semi-historical era of Mesopotamia, heroes were never given the status of gods, unlike other civilizations. Indeed Gilgamesh could merely become “two-thirds of a god” and eventually he, too, had to drink the goblet of death:

“Eternal life is indeed only the lot of gods.”

So Urdu literature gained an extremely important, interesting and respectable book on a new topic in the shape of Mazi Ke Mazar. The great progressive poet Josh Malihabadi was indeed right when he said about the book that when people of vision look at Mazi Ke Mazar they will find hundreds of cities of life emerging out of every tomb.

In Mazi Ke Mazar, Sibte Hasan writes:

“At the time of reviewing the beliefs and thoughts of an old nation, it is very essential to keep in mind its social and societal conditions otherwise we cannot comprehend the real dynamics of these beliefs and thoughts.”

In ancient societies, two concepts originated in regard to the advent of the universe and human life, i.e. the lumbar concept and the competitive concept, about which Sibte Hasan writes:

“Two concepts are found in old civilizations regarding the creation of the universe. One lumbar, the other competitive. The lumbar concept is more ancient; because the first Man had a consciousness of the act of creation from his own birth and the birth of animals. He was indeed not aware of human procreation although by experience and observation he did find out that a child is born from the belly of a woman. Like a woman, the bellies of cow, cattle, deer, bear, all their females expand and after the appointed time, alive and awake birth issues from a particular place in their bodies. Perhaps this process would have appeared very strange to people in the beginning. But then they would have become used to it. Gradually woman became the fountain-head of creation and a symbol of the growth of generations in their eyes. They also gave the earth the status of mother (woman); since water indeed emerged out of the earth; trees, plants, and vegetation grew from the earth, and indeed waved upon the bosom of the earth. So if they gave the earth the status of Mother Earth, they were not wrong. This is the reason that all the old rituals of the growth of generations and crops in every region and nation revolve around the woman indeed.”

Though the competitive concept of creation was that the universe came into being as a result of a war between two persons or forces, for example, Ishtar and Ereshkigal, Tiamat and Apsu, Yazdan i.e. light and Ahriman i.e. darkness. Sibte searches for the dynamic of the competitive concept too in the contest and conflict of human society:

“The competitive concept of the creation of the universe is the mental reflection of the contest and conflict which began at a particular period in human society. This competitive concept could not have developed in a classless society; in fact, it arose when society divided into classes. Monarchies were established and conflicts between them became a daily occurrence. Wars were fought, settlements destroyed, the blood of innocents was shed along with soldiers, and the winning rival became famous. Epics would be written in his honour and hymns and songs would be sung; so much so that every kind of goodness was attributed to his person and enemies were made into idols of evil.”

As these concepts of the creation of the universe, the prevalent concepts about the growth of generations, fate, and life after death among ancient civilizations were also a reflection of the social life and material particulars of that time. No noticeable change occurred in these beliefs and concepts for centuries. Therefore a study of ancient documents reveals that human thoughts and beliefs remained a victim of uniformity for centuries. Sibte once again points out the facts of social life while narrating the cause of this stagnation and uniformity:

“Apparently, it seems very surprising but in this entire period, very little changes are actually seen within the thoughts of the people of the valley of the Tigris and the Euphrates. It is true that within this duration, political transformations occurred there repeatedly; sometimes the flag of domination of the Babylonian empire rose; sometimes the Kassites and Iranians created an uproar; and sometimes the victories of Assur hastened. But the structure of society remained the same, rather old class relations remained in place, intact. So whether the control of priests of the temple or the principles of law and order; the methods of farming or the manners of industry and crafts, which were there in the period of Esarhaddon and Hammurabi; the same indeed remained prevalent during the time of Ashurbanipal and Nebuchadnezzar. At the most, the place of the Sumerian god Anu was given to Marduk, or Utu became Shamash, otherwise there was no fundamental change in the old rituals and customs and way of life; and it was indeed not possible for a change to happen because transformations in the way of life and style of thought of a society happen when the existence of that society decrees those transformations; and the existence of society indeed demands transformations when the old relations of production begin to become a hurdle in the path of societal progress. Then new and old ideas clash with each other; opposition to outdated relations and ideas begins and new thoughts and ideas are presented. The people of the valley of the Tigris and the Euphrates did not feel the need to change the elements of production or productive relations for about 2,000 years; the same copper tools of production and weapons of war which were used during the initial period of city-states, were prevalent in the 6th century BC at the time of Iranian dominance; neither the fundamental structure of society changed nor was there a tumult in the world of thoughts and beliefs. This is the reason neither a revolutionary personality like Zoroaster, Mani or Mazdak ever arose from the land of Iraq, nor any social movement was born which would raise a voice of protest against old superstitions and beliefs.”

Fifty years on, Sibte Hasan’s Mazi Ke Mazar has attained the status of a cult classic in the Indian Subcontinent, its value enhanced even more so now amid the cacophony of war, xenophobia and racism occasioned by Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” thesis from back in the 1990s, and amplified by the aftermath of 9/11.

When Sibte Hasan won the Dawood Prize, one of Pakistan’s highest and richest literary prizes for Mazi Ke Mazar back in 1969, he refused to accept it, since the award was associated with one of Pakistan’s 22 richest families at the time, who were part and parcel of buttressing General Ayub Khan’s oppressive and dictatorial rule in the country. Pakistan’s arch-revolutionary poet, Habib Jalib wrote the following lines in praise of his fellow traveller’s courage of refusal:

“The title which would have obliterated you, you returned,

You returned the comfort which would have left you disturbed,

Full to the brim with the blood of the friends of the nation,

You returned that chalice, my heart is full of celebration,

What would never have liberated the mind, this vice,

It was well that you returned that price,

Bravo Sibte Hasan a living writer of the country,

You returned the prize of one of the wealthy.”

Note: Original translations from Urdu by the author. First published in The weekly The Friday Times, Lahore.

The writer is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic, and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore. He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

The writer is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic, and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore. He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

The High Asia Herald is a member of High Asia Media Group — a window to High Asia and Central Asia