Filmmaker and ethnomusicologist Richard Wolf explores the meaning of a river between countries, documents the lives and musical poetry of two most prominent Wakhi musicians — Qurbonsho and Daulatsho — in the Wakhan Valley

Herald Special

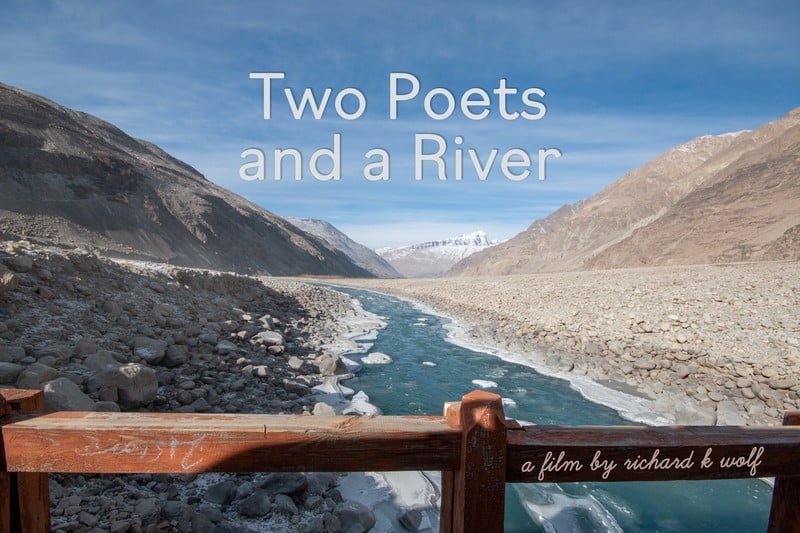

This is the story of two poet-singers who live on opposite sides of the Oxus River a border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. They share a common language, faith, and family network, and yet remain separated by the vicissitudes of the Great Game, the 19th-century conflict between the British Empire and Czarist Russia.

Professor Richard Wolf has documented the love and loss of divided families living across this divide in “Two Poets and a River,” a film about poet-singers Qurbonsho and Daulatsho, writes Lesley Bannatyne, a correspondent in the Harvard Gazette.

Prof Wolf, an ethnomusicologist, ethnographic and experimental filmmaker, who currently teaches in the departments of Music and South Asian Studies at Harvard University, in his documentary, explores what motivates musicians to be creative and why music matters.

A special screening of the film will be held at the SPCE Learning Centre, Dushanbe, Tajikistan, on May 16. The event has been organized by the Cultural Heritage and Humanities Unit of the Graduate School of the Development University of Central Asia.

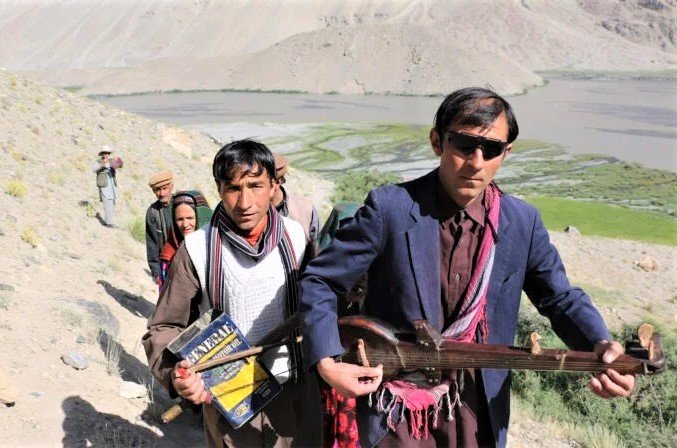

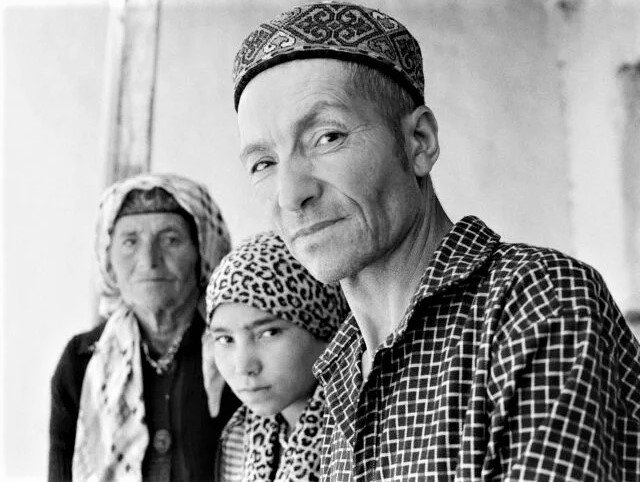

(L) Daulatsho, Yarqub, and others play their instruments and sing as they climb from Yur village to the ayloq (upper pasture). Upper Wakhan, Afghanistan, July 2016. (R) Qurbonsho sitting beside his daughter and aunt in front of his ancestral home. Vrang, Ishkoshim district, Tajikistan, July 2018. Photos by Richard K. Wolf

The film tells the story of two prominent Wakhi musicians, Qurbonsho and Daulatsho, who share a language, faith, and family network but are separated by the Oxus River.

Using the Oxus River as a topos, the film explores themes of love and loss through the lives and musical poetry of the two most prominent and innovative Wakhi musicians in Central and South Asia, Qurbonsho in Tajikistan and Daulatsho in Afghanistan.

Their Wakhan homeland became a buffer zone between Czarist Russia and the British Empire, and the river Oxus became a border during the Great Game in Central Asia. The condition of being separated by a river grounds the poets’ discussions of love and loss in their own lives as well as in their musical arts.

Wolf has a longstanding curiosity about Central Asian people and music, but his research efforts began in earnest with a Fulbright Fellowship to Tajikistan in 2012.

“I went to Central Asia to work on Wakhi music and soon came to know of Qurbonsho, a poet-singer who lives on the Tajik side of the river,” he said. “I was always curious about the Wakhis living on the Afghan side, but in 2012–13, as a Fulbright scholar, I wasn’t allowed to cross into Afghanistan.”

The border had been negotiated long ago by Britain and Russia, and Wolf was intent on crossing it, but the effort took years. In 2015, he returned to Tajikistan with names of Wakhi poets, musicians, and their villages in hand, narrates Bannatyne.

He and his small team drove for several days until the road came to an abrupt end: Melting snow had descended in torrents off the mountaintops and washed out the road and many settlements. Wolf and his companions were forced to continue into Upper Wakhan by foot, yak, and donkey. In village after village, he would hear of Daulatsho, who seemed to be everyone’s teacher and the composer of most modern Wakhi songs.

Wolf arrived at Daulatsho’s village of Yur (alt. 10,500 ft) only to find that the musician had retreated to the higher pastures where Wakhis graze their cattle in the summer months. The poet-singer finds creative inspiration in the high mountain flowers, fields, rocks, and rushing water.

“I left word that I’d return the next year. In July 2016, Daulatsho was ready for me and set me up in a one-room house. But I didn’t get much of a chance to see what was going on in the village. So I proposed making a film in order to have an excuse to see more of the village,” he said.

Wolf had used other formats to present scholarly material before — his 2014 book, “The Voice in the Drum: Music, Language, and Emotion in Islamicate South Asia,” was a work of creative nonfiction based on 30 years of fieldwork in India and Pakistan. He had been thinking about using a film to create a sequel, but his current research in Central Asia led him to postpone that plan.

“Two Poets and a River” took shape over the next several years and has been shown in the US and Europe as a work in progress.

Wolf traces the poets’ contemplations on separation, family, and environment, as well as their imaginings about what lies on the other side of the border.

The two singers knew of one another by reputation and through recordings Wolf had made, but they had never met.

In the winter of 2018–19, stranded with Daulatsho not far from the border because an enormous truck had broken down and blocked the road, Wolf realized he was close enough to pick up a cellphone signal from Tajikistan. He called Qurbonsho, and the two poets spoke to each other for the first time.

“The life experiences of these two musicians differ significantly,” Wolf said. “Qurbonsho studied in Soviet schools near his house and served as a construction worker for the army; Daulatsho had to relocate to the district center.”

He has crossed the border into nearby Pakistan but mostly stays in Wakhan. Qurbonsho lives on what he makes from performing at weddings, but no one can afford to pay Daulatsho for his performances — instead, he survives on his meager monthly salary as a schoolteacher.

Distances that can be covered in hours on the Tajik side may take days on the Afghan side. Wakhis from Tajikistan see Afghan Wakhis’ images of themselves 50 years ago. Afghan Wakhis see in their Tajik counterparts a measure of freedom and wealth.

“But as I worked with each of these musicians, I found many similarities. They share common lifeways of pastoralism, house construction, and food. Their musical poetry is based on themes common to the Persianate world. The quintessentially Wakhi song of separation, bulbulik [nightingale], inspires the art of both poets with its sparse, three-line structure. Daulatsho’s Afghan Wakhi poems tend to be lengthy but use only a few melodies. Qurbonsho writes brief, pithy poems that draw from a variety of musical styles current in Tajikistan.”

After more than 100 years of imposed division, what resonates among the Wakhis, what their poets sing and write about, comes from something more profound: love, longing, and distance from a beloved.

“My film considers the broad trope of love as well as what it means for members of a community to be separated across a national divide. I was thinking of ending ‘Two Poets and a River’ with the two men meeting in person,” said Wolf. “But I’m not sure that would be true to the spirit of love, loss, and separation that underlies the river metaphor.”

Transcript of the song:

Without you, what use is the world to me?

Food, wine, intoxication—even the sound of my voice.

Night and day I’m immersed in the pain of your love.

Lucky is a person without sadness or worry.

The 3-disc package includes 2 DVDs, a CD soundtrack of Wakhi music, and an accompanying booklet with song texts and translations.

The film has been selected for screenings at Cinque Ports International Film Festival, France and England, 2023; Association for Asian Studies Film Expo, USA, 2023; RAI Film Festival, Bristol, UK, 2023.

The film was screened at various events in 2022 including at International Council for Traditional Music Portugal; the Society for Visual Anthropology Film and Media Festival, USA; the Manchester Lift-Off Film Festival, UK; the Madrid International Film Festival, Spain; International Multicultural Film Festival, Australia; Middle East and Central Asia Music Forum, University of London, UK; Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, Harvard University, USA; and the Department of Film and Television, National College of Arts, Pakistan.

Awards

The film has won Martello Award and ICTM Prize for Best Documentary Film or Video.

The film is a must-see for anyone interested in the intersection of music, poetry, and politics. Don’t miss out on this unique cinematic experience!

https://news.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IMG_5064.jpg

Richard K. Wolf is an ethnographic and experimental filmmaker, photographer, and ethnomusicologist based in the Boston area. Wolf currently teaches in the departments of Music and South Asian Studies at Harvard University. His works include academic publications as well as an experimental ethnography in the form of a novel (The Voice in the Drum). He is also an active performer on the vina, a South Indian classical stringed instrument. His first film, Two Poets and a River, explores the lives of two prominent poet-singers on both sides of the river that divides Tajikistan and Afghanistan.