When we talk about the carpets of Central Asia, we typically mean those produced by Turkmens. However, the production of this homemade handicraft was historically widespread among other peoples of the region: Karakalpaks, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, Arabs, Tajiks, and Uzbeks, Emira Gyul. She focuses specifically on the Uzbek tradition of carpet weaving.

Carpet-weaving is an amazing art with which mankind has been familiar for almost five millennia (the first known nap structures were found among the archaeological remains of ancient Sumer). Carpets are unique in the sense that they are not just a typical home object, but an invaluable historical source, a kind of “cultural text” capable of revealing the way of life of their creators, their ways of management, the surrounding landscape, cults and religions, the twists and turns of ethnic history, connections with neighboring peoples, aesthetic priorities…

When we talk about the carpets of Central Asia, we typically mean those produced by Turkmens. However, the production of this homemade handicraft was historically widespread among other peoples of the region: Karakalpaks, Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, Arabs, Tajiks, and Uzbeks. Here, we will focus specifically on the Uzbek tradition of carpet weaving.

Ancestors of the Uzbek Carpet

Ancestors of the Uzbek Carpet

By historical standards, the Uzbek carpet is quite a young phenomenon. It emerged with the multi-tribal people now known under the collective term “Uzbek.” However, this phenomenon is based on earlier traditions associated with multilingual human collectives that played an important role in the ethnogenesis of the Uzbeks. These include residents of agricultural oases—the Bactrians, Sogdians, Khorezmians, and Ferghans—as well as representatives of the nomadic steppe world—Saka-Massagetian tribes, Tokhars, Ephtalites, Turks, Karluks, Oghuz, and other smaller groups that history records only the names of.

The last major wave of Turkic-speaking tribes to join the oases of Transoxiana, at the very beginning of the 16th century, was the Dashti-Kipchaks, with whom the ethnonym “Uzbek” spread throughout the region. One of the components of this tribal association, the Uzbek Kungrats, is now the main bearer of the authentic carpet tradition in Uzbekistan.

Unfortunately, not many antique carpets have been preserved, as wool is a very unstable material. The few such carpets that have survived to the present day have done so only because they were fortunate enough to be preserved by special natural-climatic and temperature-humidity conditions. The archaeological investigations of the past hundred years have filled some lacunas by showing the world these wonderful creations of ancient weavers.

Bactrian Rug

Intriguingly, archaeological textiles related to the territory of Uzbekistan were discovered outside the country, indicating the migration routes and broad contacts of the peoples who lived here. One example is Bactrian rugs that survived by being buried in the Taklamakan Desert (in the present-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China), which is famous for its extremely dry and hot climate. The most famous of these is a fragment presumably depicting a warrior who was one of the Tocharian aristocrats of the 2nd century BC to 1st century AD; the fragment is now kept in a museum in Urumqi.

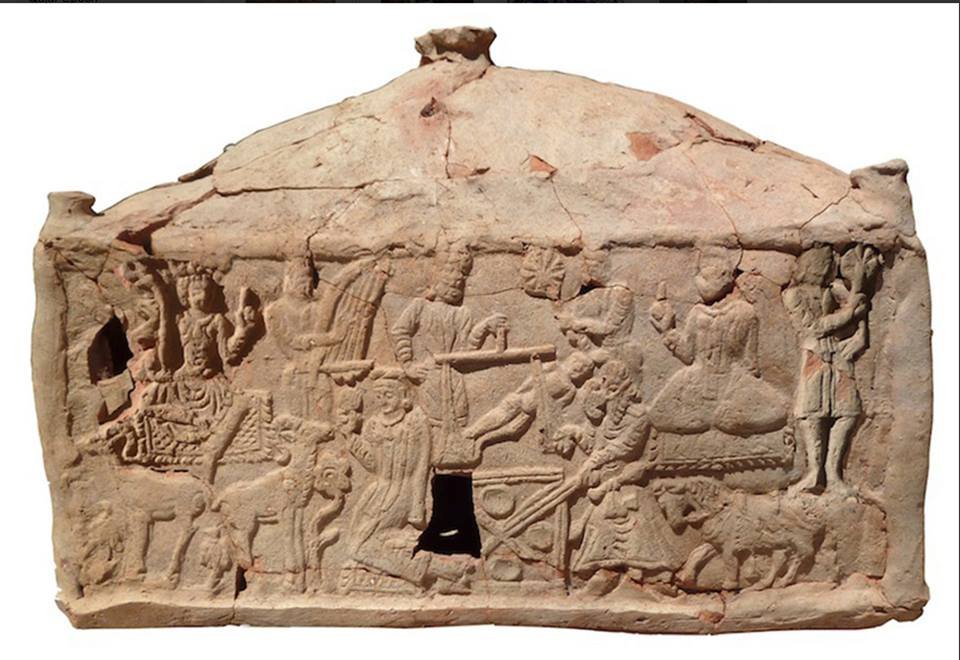

Thanks to the Mongolo-Tibetan expedition of the Russian Geographical Society led by P. Kozlov (1924-25) and the expedition of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Archaeology of Mongolia (2006-2009), embroidered carpets from the late BC and early AD period were found in the Hunnic burial sites of Noin-Ula (Mongolia), which are also associated with the culture of Yuezhi (Tocharians) (early Kushan Bactria). These colorful panels with character images are real masterpieces reflecting the cultural background of their time. They show distinct Hellenistic influence.

The Kushan-Bactrian origin of these carpets is supported by a number of facts, including the portrait image, which is identical to the image of the real historical character “Owner Sanab of Kushan (Geray)” on a silver tetradrachm from the 1st century.

These and other findings indicate that Bactria was one of the largest carpet-making regions in the ancient world. Bactrian carpets were embroidered, pile, and flat-woven wall panels with a rich graphic range, some of them undecorated.

Sogdiana Carpets

In the early Middle Ages, carpets remained an integral part of everyday life and the rituals of the local population. We see them on numerous Sogd monuments of artistic culture: wall paintings, toreutics, and ossuaries.

There is every reason to believe that real Sogdian carpets have also survived. These are rarities from the famous collection of Sheikh Al-Jaber al-Sabah of the 5th-7th centuries (held by the Kuwait National Museum). F. Spuhler attributes them to the Sassanids (from the Samangan or Maimana provinces of what is today eastern Iran). However, the images of animals in the central field and three-part half-palmettes on the edges of these carpets are more similar to the decoration of Sogdian toreutics.

Tiraz from Bukhara and Embroidered Rugs of Samarkand

Numerous written sources inform us about carpet weaving during the Muslim Middle Ages. The most famous of these is Narshahi’s “History of Bukhara” (from the 10th century). The famous historian mentions that in Bukhara there was a large workshop (bayt-ut-tiraz) where, among other things, carpets were woven, apparently with epigraphic decorations (tiraz), as on the surviving Seljuk carpets (from Konya; they date back to the 12th and 13th centuries). Narshahi’s information is the only evidence of the existence of the city carpet workshop in Transoxiana—in Central Asia, carpet weaving was still the prerogative of steppe nomads and villagers.

Another source, the diaries of Spanish ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo, who arrived at the Samarkand court of the all-powerful Timur in 1404, mentions the use of rugs embroidered with gold thread by the Timurid aristocracy.

The Oguz and Dashti-Kipchak Traditions

In the 10th century, Central Asian Oghuz tribes began a trend when they started including a gеl (medallion) in their carpet designs. The formation of the gеl style was a dictate of the time: in a period of active migration and as they were attempting to forge their own statehood, the Oghuz needed markers that would allow them to fix the hierarchical place of each tribe in the structure of the el— “people” -the union of tribes. (The word el may have been the root of the word gel.)

This style would define the image of the late medieval Turkmen carpet. Each tribe now weaves carpets solely with its own gel, which has become its distinctive sign.

Uzbeks’ carpet decorations, meanwhile, developed according to a different logic. Unlike among the Oghuz and their heirs, the Turkmens, the tradition of using identity markers on the carpets did not spread among the Uzbeks. This was likely due in part to the fact that tribal associations of Dashti-Kipchaks were more flexible: they easily disintegrated, recombined into new combinations, and mixed with each other. Often, the same groups were part of different, larger associations, losing their own names. Many shifted to a sedentary agricultural way of life, completely losing their identity. Only large tribes—namely the Kungrat and the Lakai—have preserved the purity of the family to this day. The Kungrat, in particular, followed the concept of nasl busilmasin—”not to spoil the family,” which was expressed in the rejection of mixed marriages and strict adherence to their own traditions. Even so, they did not use tribal markers in carpets, although they preserved the shamanistic symbols (cosmogonic, totemic, and tamga signs) that are generally important to nomads.

Thus, Central Asian carpet-weaving developed along two main lines: the Oghuz-Turkmen line (from the 10thcentury), which was dominated by the use of gels as “emblems” of tribal identification, and the Dashti-Kipchak (Uzbek) line (from the 16th century), the decoration of whose carpets reflected common nomadic worldviews. The two lines had much in common, as they belonged to the same circle of steppe culture, while at the same time preserving some differences in terms of the specific range of products they produced and the manufacturing techniques they deployed.

In general, the history of carpet-weaving in Uzbekistan is a history of change in the great styles associated with various ethnic groups and their religious and aesthetic preferences.

Who Wove Carpets in the 19th and Early 20thCenturies?

Unlike the earlier periods, the period of Uzbek khanates has left us a significant amount of preserved carpet material. At that time, carpet weaving in Uzbekistan existed as a kind of home craft. Carpets were woven for families’ own needs—chiefly for a bride’s dowry—and were not intended for sale. As a result, Uzbek carpets were less known than their Turkmen and Arab counterparts, some of which were created specifically for sale in the market (Arab bazaar-gilam, Turkmen beshir rugs for sale in Bukhara). The main Uzbek producers were Uzbek-Turkomans from Nurata; Uzbek ethnic groups of Dashti-Kipchak origin, the largest of which were the Kungrat and the Lakai (Kashkadarya, Surkhandarya); and members of the Uzbek population who had lost their tribal identification (mainly from Samarkand and Jizzakh regions). All of them retained a pastoralist lifestyle.

Although Uzbeks in their national consciousness, the Nurata Turkomans were genetically linked to the Turkmen Oghuz. In the 10th century, Uzbek-Turkomans became part of the Seljuk association, eventually settling in the Nura Bukhara (known in medieval written sources as the Nurata districts). The connection between Uzbek-Turkoman and Turkmen carpet traditions is clearly seen in the decoration of their carpets. Uzbek-Turkomans use the so-called kalkan-nuska (lit. “shield pattern”). The gel of the Uzbek-Turkomans demonstrates a clear affinity with the gels of Turkmens (teke-gel, yomut-gel, etc.), but its name was no longer associated with the tribal name. Evidently, the Uzbek-Turkomans preserved the medallion of the kalkan as an important symbol, but not as a label of their ethnicity.

The Dashti-Kipchaks (Kungrat and Lakai) were mainly engaged in making carpets and carpet products (various bags) using flatwoven (pileless) techniques. These were decorated in a way reflective of the Turkic steppe; the dominant medallion was kuchkorak or kaykalak (a cross with a rhombus at the base and antlers on the cross sides). This motif was the most important and widespread cult symbol in the art of all nomadic peoples in the past, a kind of “steppe mandala” and at the same time a sign of patronage to the god of Heaven, Tengri.

In the 20th century, the Kungrat, one of the largest sub-ethnic components of the Uzbek people, lived mainly in the Kamashin, Guzar, and Dekhkanabad districts of Kashkadarya province, as well as in the valleys of the Sherabad and Karatag rivers of Surkhandarya province. In the 1970s, due to the development of the Kashkadarya, the Kungrats were forced to move to Surkhandarya. As a result, one of the local provinces, Baisunskaya, has become a real reserve, where this tribal group, which faithfully preserves the traditions of its culture, including carpet making, now dominates.

As for the Lakai, due to twists and turns at the beginning of the 20th century, they migrated to the territory of mountainous Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The unique Lakai tradition of carpet making has not been preserved.

Finally, weavers from the Samarkand, Jizzakh, and Zaamin regions, although they had lost most of their tribal cultural features, remained the bearers of earlier—pre-Dashti-Kipchak—carpet traditions. During the 20th century, carpet-weaving steadily declined. Today, there are almost no women here who sit behind the carpet loom.

Types of Uzbek Carpets

The wide variety of techniques used by Uzbek craftswomen is the most reliable proof of the development of the carpet tradition. The types and techniques of classical Uzbek carpets are well-known due to the examples preserved in various museums around the world.

The first group is carpets with thick pile, or julkhirs(produced by the Uzbeks of the Samarkand, Jjizzakh, and Zaamin regions). According to V. Moshkova, julkhirs are the earliest type of knotted carpets. This conclusion was confirmed by Sir L. Wooley’s discovery of thick-pile filikli fabrics in the royal tombs of Ur (South Mesopotamia, 3000 BC). We can also see clothes made of similar fabrics on the Bactrian composite sculpture. These facts allowed a number of researchers to assert that the technique of thick-pile weaving, related to the julkhirs of the 19th-20th centuries, is the most ancient autochthonous (Bactrian) technique associated with the culture of Mesopotamia. Medallions with pearls on some Samarkand julkhirs are a replica of Sogdian silk patterns. Thus, there are distinct Bactrian and Sogdian elements in the carpets of this group.

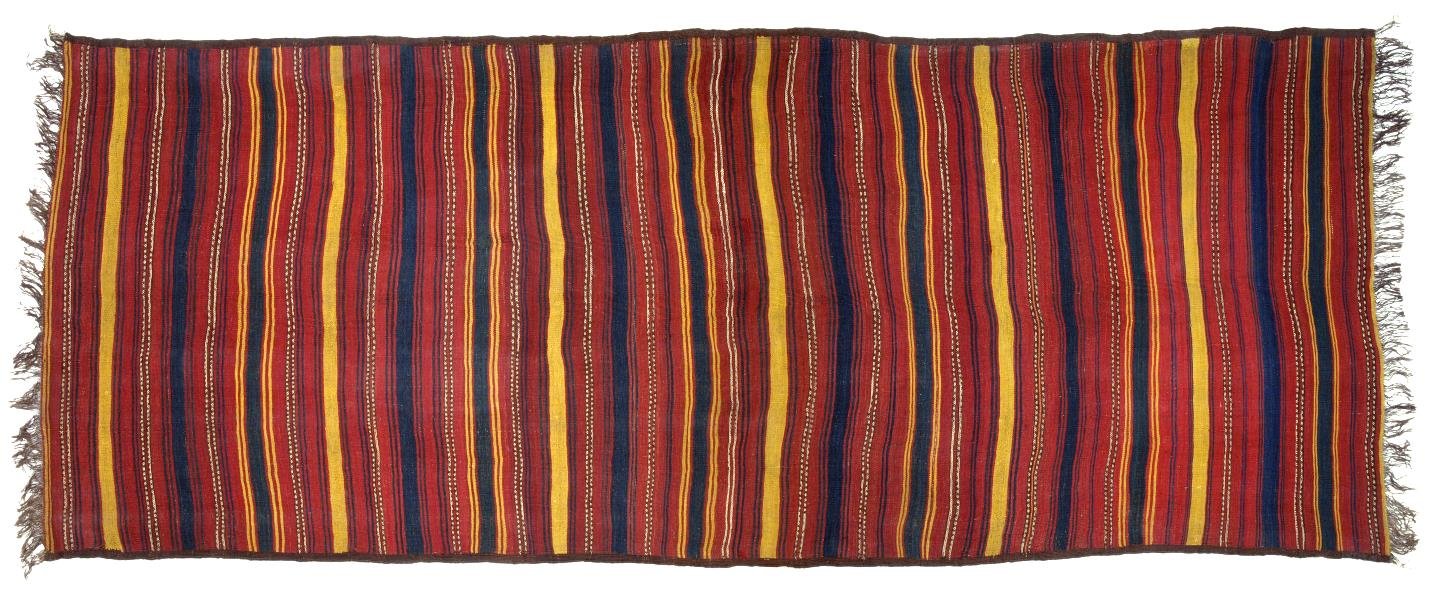

Carpets with thin pile—gilams—appeared quite late among Uzbeks. Like julkhirs, they were originally woven with separate panels on a loom with a narrow beam and then sewn together. Sewn carpets—gilams, julkhirs—are obviously based on the tradition of making baskur ribbons, which were used to tie the yurt. The more recent gilamsare solid, woven on a loom with a wide beam.

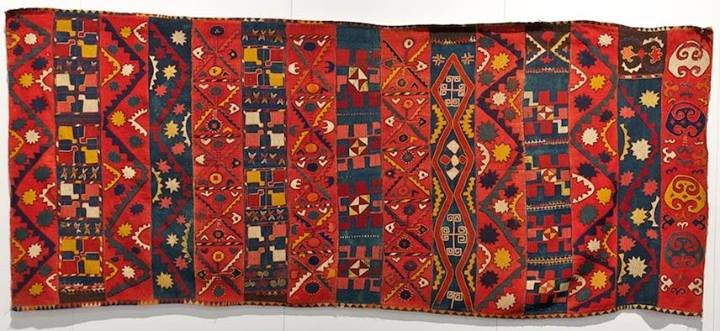

The most significant group of Uzbek carpets are flat-woven. As one of the first Central Asian carpet researchers, S.M. Dudin, noted, “Though characterized by plain and even schematic ornamental patterns, some of the Uzbek carpets by far exceeded many of those from Persia and Asia Minor in decoration and depth and clarity of colors, to say nothing of the flashy and colorful Caucasian items.” This group includes kokhma, gajari, terme, takir, and besh-kashta (produced by different tribal groups).

Sumakhi are extremely rare. Each differs in its weaving technique, but all except for takirs are woven on a loom with a narrow beam with separate panels, which are then sewn together. Gajari and besh-kashta are usually composite carpets combining panels/strips made using different techniques.

Many neighboring Turkic peoples in the region use kokhma, terme, gajari, and besh-kashta techniques. This fact allows us to consider most flat-woven products to be part of the general Turkic “steppe” carpet tradition. As for the takir, it is the Uzbek name for the kilimtechnique, known since ancient times to many peoples of Eurasia. In Central Asia, kilims were mainly produced by local Arabs (bazaar-gilam). However, the technique of kilim weaving was also used by Uzbeks.

The next group is embroidered enli-gilam and kiz-gilamcarpets produced by Kungrat and Lakai. They were the most important part of a wedding and were used mainly as curtains. Embroidered carpets are a special page in the history of carpet-weaving, clearly dating back to the embroidered carpets of ancient times (embroidered carpets from Noinula, finds from 1924-25 and 2006-09).

Enli-gilam is a composite carpet combining stripes/panels made in different techniques (enli means wide, i.e., a carpet with a wide embroidered stripe). It has three varieties: ok-enli (with a white stripe), kyzyl-enli (with a red stripe), and kara-enli (with a black/brown stripe). The decoration of these carpets is very diverse and should be the subject of special research.

Kiz-gilam, or girl’s carpet, is red, rarely white. Unlike enli-gilam, its only decoration motif is the aforementioned kaykalak, a capacious symbol of life that is fundamental for all peoples of the steppe. Its diagonal coloring brings the Kungrat and Lakai carpet traditions closer to the Turkmen one—some Turkmen gels are also colored diagonally, with two quarters of one color and two of another. During wedding celebrations, embroidered carpets played not only a decorative but also a magical and protective role. The name kiz-gilam is a convention; the original name of carpets of this type has not been preserved, while the production of kiz-gilams stopped even among the Kungrats themselves.

In the recent past, Uzbeks also had three types of felt carpets: pressing felt rugs, embroidered carpets, and stitched rugs. Today, only the production of pressing felt rugs is preserved, in Surkhandarya.

Thus, the art of the Uzbek carpet is a synthesis of the dominant Dashti-Kipchak heritage and the carpet traditions of other Uzbek tribal groups living on the territory of Uzbekistan. In the latter, earlier artistic traditions, particularly Bactrian and Sogdian, are more noticeable.

The classical Uzbek carpet (pile, flat-woven, embroidered) retains its archaic features both in terms of aesthetics and manufacturing technology: it is woven on a horizontal loom with a narrow beam, in separate strips/panels (takhte), which are then sewn into a solid canvas. The vertical loom appeared in Uzbekistan only in the 1930s, as a means of optimizing working conditions in artels.

Uzbek carpet decoration is mainly connected with shamanistic (Tengrian) benevolent symbolism (equilateral cross as a kind of steppe “mandala,” Jupiterian 12-year-old “calendar” as a model of cyclical time, eight-pointed star), totemism (zoomorphic symbols, tamgas), fertility cult (plant motifs). The decoration is laconic, as the symbols themselves are laconic, and at the same time very informative, full of deep meanings that were gradually losing its significance in the 19th century. By the beginning of the 20th century, the masters had forgotten the meanings of sacral signs; Tengriism and its attendant cults had given way to Islam in everyday life and religious consciousness, but not in traditional craftsmanship, for which the images linking pastoralists to their past were still valuable.

Traditional craftsmanship still valued images linking pastoralists to their past

The late medieval Uzbek carpet is a unique cultural monument that was developed over the course of centuries. It has become even more valuable in the context of the disappearance of nomadism as a civilizational phenomenon. In her time, ethnographer Balkis Karmysheva proved that the “nomadic steppe” was not only outside of Transoxiana, but also “inside itself.” The carpet, as an expression of the creative potential of Uzbek tribal groups, is an invaluable source that sheds light on the history and artistic ideals of the steppe world, which was an important part of Uzbekistan’s cultural heritage.

After experiencing a decline for most of the 20th century, carpet production in Uzbekistan is now having something of a renaissance. However, the modern products made in various private factories are often far from authentic traditions. A genuine Uzbek carpet remains a stranger in the bosom of its own culture. Only in a number of provinces, such as Baysun in Surkhandarya, is this age-old art still alive. However, there are also clear signs of its decline. Creating a modern brand of authentic Uzbek carpets is an urgent task of our time.

The article is based on the monograph “Carpets of Uzbekistan: History, Aesthetics, Semantics” by Elmira Gyul, which was first published in the Voice on Central Asia web pages

![]() Elmira Gyul is Chief Researcher at the Institute of Art Studies of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, an Associate Professor at the National Institute of Art and Design named after K. Behzoda, Tashkent, Department of Art History, and a lecturer in the Republican Scientific Consulting Center NC Uzbektourism.

Elmira Gyul is Chief Researcher at the Institute of Art Studies of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, an Associate Professor at the National Institute of Art and Design named after K. Behzoda, Tashkent, Department of Art History, and a lecturer in the Republican Scientific Consulting Center NC Uzbektourism.